Kyoto

Kyoto reminds me of Florence: it's an average, not to say shabby, city studded at random by isolated spots of absolutely stunning beauty and cultural heritage. This is made all the more stark in Kyoto because so many of the jewels are behind their own walls, and so one passes through the gates and Alice or Dorothy-like are transported into this totally different universe.

Kyoto reminds me of Florence: it's an average, not to say shabby, city studded at random by isolated spots of absolutely stunning beauty and cultural heritage. This is made all the more stark in Kyoto because so many of the jewels are behind their own walls, and so one passes through the gates and Alice or Dorothy-like are transported into this totally different universe.

Whilst I appreciate a lot of Christian buildings for their architecture, engineering, or historical value, I'm too much of a heathen to feel much in terms of spiritual energy. By contrast, some of the buddhist sites in Kyoto had so much energy I was pushing against a headwind all the way around. I had to do two laps around Daisen-In and I still couldn't drag myself away.

The first thing you experience in Kyoto is the railway station of course. And they are so proud of it that there are photos of it in my Guide Book. That's Adam standing in front of it. It's just as imposing on the inside, with parts of it open from street level to the ceiling. The other snap is a closer view of the walkway just behind Adam, spraying a mist of water to cool off pedestrians, and the lady is using her umbrella as a sunshade, not protection from the vapor.

The first thing you experience in Kyoto is the railway station of course. And they are so proud of it that there are photos of it in my Guide Book. That's Adam standing in front of it. It's just as imposing on the inside, with parts of it open from street level to the ceiling. The other snap is a closer view of the walkway just behind Adam, spraying a mist of water to cool off pedestrians, and the lady is using her umbrella as a sunshade, not protection from the vapor.

- Daisen-in

- Ryoan-ji

- Kinkaku-ji (Golden Pavilion)

- Fushimi Inari Shrine

- Ginkaku-ji (Silver Pavilion)

- Sanjusangen-do

We took the bus out towards the north-west of town, where we knew the first three temples on our list appeared to be walking distance from each other. We were surprised at how few other tourists were on the bus: none. Or at least no foreigners. We got to a stop that looked like it coulda, shoulda, woulda, been the right place and one person got off. Surely if this was the right place there would be a mass exodus? Or at least a sign? The doors closed, the bus moved away, and immediately made the sharp right-turn that confirmed that indeed we just missed the stop. I rapidly recalculated on the map and agreed with Adam that we'd wait two more stops, and get off "at the other end" and walk back visiting the temples in the opposite order. We got off, and started to walk. It was hot as hell. The little cars made almost no noise on the street, contributing to a sort of otherworldly feeling. Where was everyone? We had to ask in a store to confirm we were still heading in the right direction.

Finally an itty-bitty sign pointed up a totally nondescript side street. Another 150 yards, and the left side of the street opened to this huge entrance. Daitoku-ji is a temple of the Rinzai school of Zen in Buddhism, one of the five most important Zen temples of Kyoto. The name means "The Academy of the Great Immortals."

Finally an itty-bitty sign pointed up a totally nondescript side street. Another 150 yards, and the left side of the street opened to this huge entrance. Daitoku-ji is a temple of the Rinzai school of Zen in Buddhism, one of the five most important Zen temples of Kyoto. The name means "The Academy of the Great Immortals."

There was nobody at the gate, just a small sign saying something along the lines of "some are open, some are closed, knock on the door of an open one if you want to be admitted. No maps, no arrows. We started to wander through the buildings, totally unable to distinguish between "open" ones and "closed ones". Finally again there was another little sign stating Daisen-in: Entrance This Way.

Daisen-in is a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji, one of the collection of world-class temples, clustered together behind this fittingly grand entrance, but even inside the lack of tourists, and the lack of signage continued to be baffling. It probably goes without saying that Daisen-in is the most famous sub-temple. Why else would we be here?

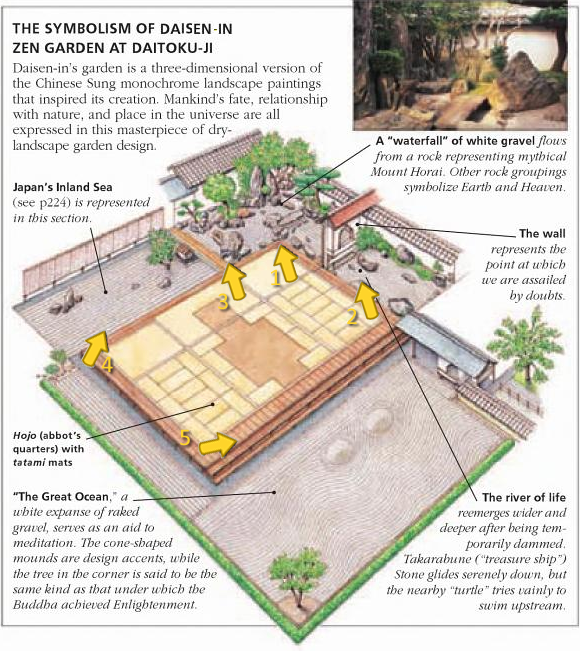

Daisen-in Temple was founded in 1509 by the Zen priest Kogaku Sotan (1464-1548) upon his retirement as abbot of Daitoku-ji. The hojo, his residence, was completed in 1513, and the garden that surrounds that structure probably dates from the same period. This stunningly beautiful garden is one of the greatest in Japan. Large rocks have been arranged in a miniature landscape whose vertical rocks suggest the mountains from which a waterfall and its resulting river flow. The garden takes a determinedly literary approach. The"river" of white gravel representing a metaphorical journey through life; begins with a dry waterfall in the mountains, passing through rapids and rocks, and will eventually end in a tranquil sea of white gravel with two gravel mountains (Picture 5).

Daisen-in Temple was founded in 1509 by the Zen priest Kogaku Sotan (1464-1548) upon his retirement as abbot of Daitoku-ji. The hojo, his residence, was completed in 1513, and the garden that surrounds that structure probably dates from the same period. This stunningly beautiful garden is one of the greatest in Japan. Large rocks have been arranged in a miniature landscape whose vertical rocks suggest the mountains from which a waterfall and its resulting river flow. The garden takes a determinedly literary approach. The"river" of white gravel representing a metaphorical journey through life; begins with a dry waterfall in the mountains, passing through rapids and rocks, and will eventually end in a tranquil sea of white gravel with two gravel mountains (Picture 5).

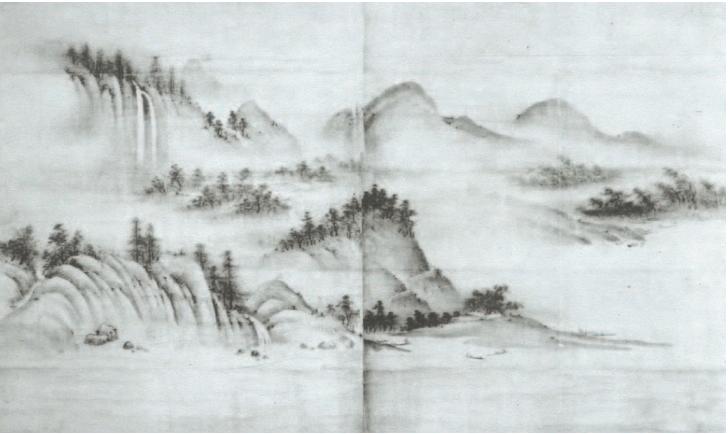

While the theory that other early Zen gardens were intended to imitate Chinese landscape paintings or their Japanese equivalents is open to question, there can be little doubt that this was the intention at Daisen-in (compare this to Ryōan-ji).

The garden employs all the elements of a classic Sung-dynasty Chinese landscape painting, but brings a three-dimensional form in a garden which surrounds the main hall on all four sides. As noted above, the dry river landscape is a metaphor for the journey of life - from the narrow rapids of youth to the more mature stream of adulthood. Rocks symbolize human trials and tribulations. Eventually, the river empties out into a flat void of white gravel which symbolizes the void of death to which all travelers return. Further out stands a lone Bodhi tree beyond two gravel cones, which represent the obstacles to the attainment of enlightenment.

Two major problems here: first we were expressly forbidden to take photos. In the confined space, and not exactly an abundance of light, it would have been a challenge anyway, but I hated having to rely on the gift shop choices which typically left much to be desired.

Second problem: incredibly, even with the entire interweb at my disposal, photos that even begin to do justice to this beautiful place were few and far between. So to try to give some context, I've stolen the excellent sketch from my trusty Eyewitness Travel Guide To Japan, which miraculously I was able to find online. To that plan I added the arrows, which show the position and orientation of the five images that follow. But for reference, by far the best site for photos is this one at Bowdoin.

Picture 1: The "Main" Garden

Picture 1: The "Main" Garden

Daisen-in Temple's main hall is one of the few original buildings to survive the fire that destroyed much of Daitoku-ji Temple. It is one of the oldest remaining examples of the Hojo style of Zen-Buddhist architecture, and its painted screens are also masterpieces.

Anyway, we were finally here, removing our shoes and paying our entry fees at my first Kyoto temple, and probably the one I was most looking forward to. High expectations, all too often not met when you've built something up for so long. No such problems here. Daisen-In quite literally takes your breath away. You turn the last corner and there you are, roughly where the "2" arrow is in the plan above.

The cedar floorboards were smooth as silk, and warm from the sun. It's funny, I know Adam was there, and there were a few other tourists, but I was on my second lap before I became aware of any off them again, when I started to read stuff to Adam from the English language guide I had grabbed. Until then I must have tuned everybody and everything else out. I just tried to drink everything in, trying to burn the images into memory. At that point of course I had no idea if I would be able to find anything to substitute for my lack of photographs.

Picture 2: The Wall Of Doubt

Picture 2: The Wall Of Doubt

The "main" garden (Picture 1) is composed of rocks suggesting mountains and a waterfall, clipped shrubs and trees representing a forest, and raked white gravel representing a river. The "river" splits into branches, one of which flows through "The Wall Of Doubt" (Picture 2) to a larger "Ocean" of white gravel. In the river are several symbolic stones; one resembles a "treasure ship" moving with the current, and the other resembles the back of a turtle trying to swim upstream.

The other branch flows into a "Middle Sea" of raked white gravel and a few rocks (Picture 4); but before it does so, it flows though this last section on the "main" garden" (Picture 3).

The flat rock in the middle and on the left side of PIcture 3 is Buddha's footprint. The footprint is the indentation in the rock. It is filled with water, and never dries up. The Buddha is powerful enough to turn the gravel representing water in the river flowing around the footprint into actual water.

Then on to the "Middle Sea" aka "Japan's Inland Sea" (Picture 4) not nearly so powerful, so keep going around the corner, the floorboards squeeking like the "twittering of nightingales" a design feature to let the occupants know of an intruder without letting the intruder know that the alarm has been raised.

Picture 3: "Buddha's Footprint"

Picture 3: "Buddha's Footprint"

Finally, "The Great Ocean" (Picture 5). No surprise to me that these last two are thought to be later additions to the main gardens. I was struck by the symmetry of the pillars or mountains which were lined up perfectly with a pair of Buddhas or bodhisattvas that guarded the main sacred space inside the hojo, but I can find no reference to this in the literature.

The screens in this room were not much to look at (just me) but as an indicator of their value, when they were leant to The Louvre for an exhibition there, The Louvre sent Venus de Milo in exchange. It was incredibly difficult finding any sort of image of them on the web, or even in the material I bought at the site. To my frustration, there was much more (unrepeated) material in the guide I was obliged to turn in at the end of the visit than all the other sources put together. We spent a few minutes inside the hojo, but it was no match for the gardens, and instead I returned to do another lap around the outside.

Picture 4: Japan's Inland Sea

Picture 5: The Great Ocean

Finally we had to drag ourselves away, and returned to the gift shop to see what we could find to suppliment my fickle memory. The most surprising thing we found was the abbot, sitting behind the desk with the docent. For a suitably princely sum,

Sŭki (for 'twas he) would write a dedication then sign your name and his inside a very beautiful but entirely Japanese book on the temple. Priceless. It also contained the photos I needed. We both bought one.

Finally we had to drag ourselves away, and returned to the gift shop to see what we could find to suppliment my fickle memory. The most surprising thing we found was the abbot, sitting behind the desk with the docent. For a suitably princely sum,

Sŭki (for 'twas he) would write a dedication then sign your name and his inside a very beautiful but entirely Japanese book on the temple. Priceless. It also contained the photos I needed. We both bought one.

Since we'd already spent a fortune, and since we already knew that our hosts at the weekend had been unable to track down an official tea ceremony for us (surprisingly hard to find, considering how famous a tourist attraction they appear to be) we accepted an invitation to the Daisen-in's $5 version. In hindsight this was probably smarter than we first realized: after only 5 minutes of kneeling/sitting on our ankles neither of us could feel our feet, so the only way to get up was to first roll over on our backs and slowly unfurl our legs again. A full-blown ceremony might have left us crippled for life. But it was neat watching the matcha being whisked up into a froth and then the old woman serving it was patient enough to show us how to hold the bowl in our right hands and cradle it in the palm of our left. You then turn it clockwise about 90 degrees. Raising the bowl with both hands, the matcha must then be consumed in three (count 'em) gulps. The flavor and texture were both a shock, as was the strengh of flavor. Thick as a milkshake, and a bold, almost meaty flavor, it bore absolutely no relation to any kind of green tea I'd had before.

The tea came with a free "sweet", a rather non-descript thing covered in cocoa powder, but of course I could not eat it until I got outside into the daylight to photograph it. And then we were done. Absolutely fabulous from start to finish. We can go home now, mission accomplished. We spent a little while wandering around the rest of Daitoku-ji, and found at least one other temple to wander through, but it definitely wasn't in the same class, so eventually we found ourselves back on the street, and looking for lunch.

We still had this remarkable off-the-beaten-track feeling: here we were walking between some of the world's greatest highlights, and along with no signage, there was no infrastructure either. No bars, restaurants, hot-dog stands, souvenir shops, nothing to give away where we were. Eventually we found a lone restaurant/diner/cafe, and gratefully headed inside, for re-hydration and cooling purposes if nothing else. But in fact the soba noodles were excellent, and as Adam predicted, a big hit. I loved the play of the cold noodles and the hot miso. Then on to Kinkaku-ji.

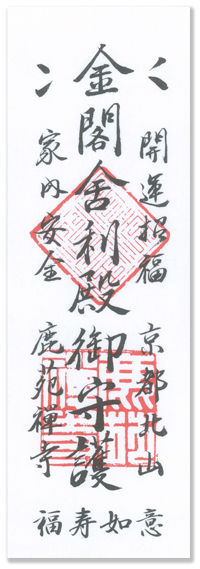

Kinkaku-ji was built by the third Ashikaga shogun Yoshumitsu (1358 - 1408), who entered the priesthood at the age of 37. The temple was his retirement villa. A fervent follower of the Zen priest Soseki, Yoshimitsu directed that the villa become a temple after his death, with Soseki as its abbot. Although it felt like every one of the historical buildings we visited had been rebuilt multiple times over the centuries (wars, fires, earthquakes, the usual things) this was the only one that listed arson as a cause. Even more surprising, it was in the modern era: 1950.

Kinkaku-ji was built by the third Ashikaga shogun Yoshumitsu (1358 - 1408), who entered the priesthood at the age of 37. The temple was his retirement villa. A fervent follower of the Zen priest Soseki, Yoshimitsu directed that the villa become a temple after his death, with Soseki as its abbot. Although it felt like every one of the historical buildings we visited had been rebuilt multiple times over the centuries (wars, fires, earthquakes, the usual things) this was the only one that listed arson as a cause. Even more surprising, it was in the modern era: 1950.

If Daisen-in garden was an exquisite addition to its temple, the Golden Pavillion was an exquisite addition to its garden. Maybe folks visiting Kyoto only have time to see one temple. And if that's true, I guess it would make sense that you'd pick this one. But seriously, the busloads of tourists here simply deepened the mystery of how few there were everywhere else. And who comes all this way and then only visits one temple? Now we were fighting off school kids with a stick, waiting in line to get a good shot. And one of the reasons for the line was our first experience with the photo-op spot. A several hundred year old photo-op spot perhaps, but a spot nevertheless. To get the best impression of what this was like, click here to see the panorama that is your first introduction to the garden. If you can do that before you scroll any further, so much the better.

The drama is built up brilliantly. Having come through the payment area, one proceeds along a tree-shaded path which turns a corner to suddenly emerge into the bright garden, with Kinkaku-ji appearing to be floating on the other side of a large pond.

Granted I have absolutely no authority to speak on the subject, but I have this totally unresearched theory that Christian and Islamist leaders like their followers to be in awe of their god, and they conciously built their structures to put their followers in that frame of mind. A thousand years later, even a heathen like myself still find the light and space of York Minster or Notre Dame, to name two purely at random, to be absolutely breath-taking. At the time they were built it must have been like introducing a country bumkin to the Empire State Building.

Granted I have absolutely no authority to speak on the subject, but I have this totally unresearched theory that Christian and Islamist leaders like their followers to be in awe of their god, and they conciously built their structures to put their followers in that frame of mind. A thousand years later, even a heathen like myself still find the light and space of York Minster or Notre Dame, to name two purely at random, to be absolutely breath-taking. At the time they were built it must have been like introducing a country bumkin to the Empire State Building.

By contrast Buddhism feels so much more introspective, contemplative, human-scaled. In other words, I like my Christian/Islamic jestures to be magestic, powerful, and my Buddhist ones to be small, exquisite, humble. Humble? The Golden Pavilion is covered in gold-leaf. But look at it. It is utterly exquisite. It is made even smaller than its actual dimensions by being placed in the middle of several acres of garden. I was reading The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima as my vacation-related reading project (highly recommended by the way). Mizoguchi, the subject of the story, is an acolyte at the Golden Pavilion in the years immediately after the second world war, and culminating of course in the 1950 arson attack. He is obsessed with the idea of beauty and whether or not the Golden Pavilion (or anything else for that matter) can ever match up to a standard set by his mental model. By focusing so entirely on the beauty, any conflict with ostentation was diluted to insignificance. So in my book anyway, it can be painted in gold and yet still be humble.

|

A stroll garden then. So after spending 15 minutes or so gazing at this stunning view, with every little rock island and every tree worthy of a photographic study of its own, we set off on the stroll. It took us round behind the pavilion and a closer look at the (bronze) Phoenix glowing on the roof, close enough also to the pond, so that the carp started to gather to see if we had anything for them. Then on back and around, until the top tier of the pavilion and the Phoenix were the only parts you could see above the tree tops. There were some other buildings back here, an old tea room with moss growing on its shingle roof, and a much smaller shrine which I would swear was shinto, even though that makes no sense. It was all very pretty, and immaculately kept, but as Eyewitness Travel seemed to imply, the real bang for the buck was that initial vista, the staged setting for the Golden Pavilion. And if that was the stage, the rest of the garden was definitely backstage. |

|

So it was not long before we found ourselves back in the parking lot, and then back on the street. On to the final objective, where we should have started out the day, Ryoan-ji.

So it was not long before we found ourselves back in the parking lot, and then back on the street. On to the final objective, where we should have started out the day, Ryoan-ji.

As ever working with less than stellar maps, and the usual lack of signage, we came across a temple roughly where we expected Ryoan-ji to be. We walked in through the long entrance looking for clues. It was cute enough, but didn't seem right. Eventually we found an occupied building (unmarked of course) but it had a window and somebody sitting staring out of it, so clearly someone provided to take money and/or answer questions. Our question was so familiar that he simply slide a color map over to us, drew a big circle over one spot while pointing at the ground with his other hand, and then said "Ryoan-ji" while he drew a big circle around another spot. Between the two circles big fat red arrows plotted the route back out to the main road, around a couple of corners and finally, indeed, to Ryoan-ji's entrance. Alrighty then.

To get the best impression of what this was like, click here to see the panorama.

Ryoan-ji was founded in 1450 by Hosokawa Katsumoto who was deputy to the Ashikaga shogun. Katsumoto invited the 5th abbot of Myoshinji, Giten Gensho to be its founder. Like many Japanese historical sites, this one has been destroyed multiple times, the first time only 20 years later, during the Orin War. Katsumoto's son Masamoto rebuilt it. Giten, Katsumoto, his wife and son Matsumoto are all buried here.

Ryon-ji's main claim to fame, and the principle driver for it being on our list is its rock garden. Comprising just 15 stones set in a sea of white gravel, it is regarded by many as the ultimate expression of Zen Buddhism. No one seems too certain what the stones symbolise, and as our trusty Eyewitness Guide: Japan says "Its riddles can be unravelled only by silent contemplation, something that the hordes of high-school students, not to mention the temple's recorded explanations, do little to facilitate." We got lucky. Though we got there long after the gates opened, and there was definitely a good crowd present, it seemed suitably reverential. I was able to happily sit on the warm boards and quietly contemplate the scene. Alas, though I gave it well over five minutes, perhaps even ten, no riddles were unravelled for me.

Part of the mystery is that the garden's builder is also unknown. A favorite candidate is the painter Sōami, who also painted the screens at Daisen-in, but there are plenty of other candidates. The only thing that is clear is that it was built during the Muromachi period (late 14th through 16th century) though narrowing it down to a 150-200 year period hardly feels exact. The most likely date, and the one quoted on Ryoan-ji's official website, is 1499, when the hojo (residence) building was constructed.

It turns out that one of the reasons that one is enticed to stare is that an optical illusion is built in. Although it looks level, the entire garden slopes gently to the top left corner, and despite that, the wall is actually shorter at that end than at the temple end—you can actually see that in the photo now I've pointed it out. The net effect is to magnify the perspective, so the garden looks bigger than it is. Armed with these conflicting messages, your mind seems to want you to just stare. Mission accomplished.

It turns out that one of the reasons that one is enticed to stare is that an optical illusion is built in. Although it looks level, the entire garden slopes gently to the top left corner, and despite that, the wall is actually shorter at that end than at the temple end—you can actually see that in the photo now I've pointed it out. The net effect is to magnify the perspective, so the garden looks bigger than it is. Armed with these conflicting messages, your mind seems to want you to just stare. Mission accomplished.

The wall itself is also interesting. It is an earth wall, and the loam has been mixed with rapeseed oil (canola) to "protect it from the glare of the white sand." This mixture turns out to be highly durable, able to withstand many years of exposure to the region's dramatic seasonal climate changes.

We took the bus back into town. As usual there were not many people on it, or at least until we came to a stop where about 30 young guys in uniform were waiting. Svelt as Adam and I are, experience had taught us that our rears were considerably wider than the standard Japanese seat, so generally we did not sit together. But with this potential onslaught I moved over and we wedged ourselves onto one bench. The solitary soldier who got on the bus clearly thought we were a pretty odd pair, as did the few other occupants who'd watched the whole scene. As the bus pulled away leaving the rest of the squad at the bus stop, I extracated myself and went back to my own bench. We'd have cared if we were not laughing so hard. The audience went back to looking out of the window.

After returning to the hotel for a shower and change of clothes we set off again on the prowl for supper. We walked passed Nishi and Higashi Hongan-ji Temples, two almost identical buildings, side by side and only a block from the rail station. One of them was completely enclosed in one of the biggest sheds I've ever seen. It needed to be substantial: one of the halls in the complex claims to be the largest wooden structure in the world, the other one looked just as large to me, so must be #2. Either way, too big for me. We took it all in, took a few pictures because one should, but then moved on.

In another mile or so, and with night falling, we found ourselves in the main shopping district, and then crossed the river into Gion, Kyoto's best-known geisha district. The street we strolled up and down comprised the long, low, wooden buildings of old Japan that we would become so familiar with in Takayama, and on the Nakasendo, and in stark contrast to the bright lights of the modern city we'd left moments ago on the other bank of the river. It was just as bustling this side, but lit solely by the lanterns hanging outside the inns, restaurants and teahouses. Somehow the place gave off a vibe that it was wholely beyond the price range of the plebs like us who were on foot. This feeling was aided by the occasional limo that floated through the crowd, stopping briefly to let their charges scurry into the safety of their chosen hostelry. Finally just as we were leaving, it was completely confirmed by the momentary scene, scarred into my memory, of a genuine geisha trying to shuffle the 20 yards from whereever she'd been prepping to whereever she was working. Despite having three or four handlers around her, she nearly lost her footing in the crush of onlookers trying to grab a better look, or better still a photo. It made me sick to my stomach, and I conciously looked to make sure that the offenders were not just the few westerners in the throng. I got some small glimmer of relief from confirming that, contrary to type, the locals were just as bad. Just accidently being on the periphery of the mob made me feel dirty enough to need another shower. We hurried on.

We'd now been on our feet a good twelve hours, with at least two miles to go to get back to the hotel, and we still hadn't eaten. Even Adam was so tired that he needed to find one of those places where we could just point at pictures on a printed menu, and pay by shoving money into the kiosk by the door rather than having to negotiate. We finally found one he liked, and flopped down at an empty table. A huge bowl of I-don't-know-what, miso soup, unlimited rice, and a beer worked wonders.

We'd now been on our feet a good twelve hours, with at least two miles to go to get back to the hotel, and we still hadn't eaten. Even Adam was so tired that he needed to find one of those places where we could just point at pictures on a printed menu, and pay by shoving money into the kiosk by the door rather than having to negotiate. We finally found one he liked, and flopped down at an empty table. A huge bowl of I-don't-know-what, miso soup, unlimited rice, and a beer worked wonders.

We set off again, re-passed the largest wooden structures in the world, and were within a quarter mile of home when we came across a small alley lined with bars. Multiple tragedies. The only way you could tell they were bars was the smell, and a patron was coming out of one as we passed, giving us a peek through the open door. Each bar was two double sliding doors wide. The bar ran pretty much the whole length, but the most interesting part was that there was about the same amount of room on the barkeep's side as there was on the customer side. You sat down on the empty stool, turned around and slid the door shut. It was so close you could lean back on it. So you had to open the correct door, there was no way to move around once inside the bar. So maximum capacity was perhaps a dozen patrons. We found the only one with two free stools next to each other, and slid the door up behind us. We were warmly greeted, and immediately a dish of pickles arrived. The whole bar seemed to approve of our desire to drink local brews. I think Adam had a Sapporo and I had shōchū. There was another murmur of approval when they learned that our next stop was Hiroshima. To my horror, despite its cramped confines and how tiny the audience, someone fired up a karaoke machine. I haven't tried karaoke because I hate it. Hate it. Worse than dancing. But here's the thing. There was absolutely no sense of ridicule or shame. On the contrary, the audience seemed more appreciative and encouraging the worse the performance. It was like a sort of group therapy, everyone helping everyone else out of their shells. Perhaps that's what it is like in other countries too, but given our TV appetite for laughing at one another rather than with one another, it's hard for me to imagine.

Fushimi Inari-taishi

The next day we devised a cunning plan. The Fushimi Inari Shrine out to the south-eastern edges of town promised some interesting pictures, but the bus-train-bus thing seemed too much of a hassle for a place that only seemed to be about 10 minutes by cab. Instead the plan started with a cab from the station. Then we would take a train back from Fushimi to the north-eastern side of town, and walk back along the Philosophers Path, a canal-side walk, said to be very popular especially in the cherry-blossom season. At the top of the walk was also The Silver Pavilion—not on my A-list but we should check it out since we were in the area. Best laid plans and all that, but as usual we would just take one thing at a time until time ran out.

So after breakfast, and after hanging out for a while while Adam ran back for his rail pass—again—and by then the camera shop was open so he could buy some more memory, we grabbed the cab from the station and were driven out to Fushimi Inari Shrine. From early times, Inari was seen as the patron of business, and therefore merchants and manufacturers have traditionally worshipped the god. Each of the torii at Fushimi Inari is donated by a Japanese business. First and foremost, though, Inari is the god of rice.

So after breakfast, and after hanging out for a while while Adam ran back for his rail pass—again—and by then the camera shop was open so he could buy some more memory, we grabbed the cab from the station and were driven out to Fushimi Inari Shrine. From early times, Inari was seen as the patron of business, and therefore merchants and manufacturers have traditionally worshipped the god. Each of the torii at Fushimi Inari is donated by a Japanese business. First and foremost, though, Inari is the god of rice.

Once again, signage was remarkably lacking. If it wasn't so unthinkable, I'd have said we'd been dumped somewhere convenient but random. It was a narrow shopping street. One store appeared to sell nothing but chop sticks. The driver pointed up an alley on the other side of the street, so we headed up it. Sure enough, it was a side entrance to the shrine, and we came in at the top of a grand main avenue down the hill. It would have been more spectacular to approach from the bottom, but oh well. We walked down the hill some to get the shot everyone else seemed to be taking, with this massive torii framing the temple.

The earliest structures were built in 711 on the Inariyama hill in southwestern Kyoto, but the shrine was re-located in 816 on the request of the monk Kūkai. The main shrine structure was built in 1499. At the bottom of the hill are the main gate, "tower gate" and the main shrine. Behind them, half way up the mountain, the inner shrine (okumiya) is reachable by a path lined with thousands of torii which was the attraction that had drawn us to the site in the first place. At the top of the mountain are tens of thousands of mounds for private worship. We looked around for the avenue of torii, and eventually found it behind the temple.

|

Maps on sign posts seem to indicate that the avenue wound all the way up Inari mountain to the shrine at the top. It looked hopelessly out-of-scale, but the improbable implication was that it was a mile or more to the top. I looked at Adam. Adam looked at me. "The rule is, we take as long as it takes, right?" "It is," I agreed. It was hot, as usual. 90°+F 30°+C as usual, and we only had one bottle of water between us, but a rule is a rule. We were rewarded immediately. We both kept stopping every few seconds to try to get a better shot. With people, without people. Without sometimes took a while. Just like traffic when you are pulling across a road, just as the view was about to clear in one direction, someone would appear coming from the other. Remember: each torii is an individual donation. It's a mile or more to the top. The backs of the torii were inscribed, presumably with details of the donor, or the donor's wishes. They thinned out a little after a while, but not much. |

|

Every so often we would come across an obviously new one, and at one point workman were busy preparing the huge poles that would soon become a particularly large specimen. They were manoevering one of the massive posts into its hole. Not as tall as a telegraph pole but twice as wide at the bottom it was as much as the three workmen could do to move it, even though it was balanced on a dolly. By the time we got to the fuelling station about one third of the way up we were drenched in sweat. There were several stores selling knick-knacks and more importantly cold drinks and ice cream in which they were doing a steady business. It was also enough for 80% or 90% of the crowd for whom this counted as far enough (and there was a good view out across Kyoto), and so after downing one bottle of water and stashing another we set off again on a markedly lonelier road. Just the way we like it.

We passed several shrines, and the "main" one was so unassuming that combined with the lack of view we were someway along the downhill loop before we convinced ourselves that the last shrine had indeed been the summit. So not overly impressive then. Therefore, speaking for myself I admit, the real highlight of the pilgrimage was another store shortly after the summit. In addition to torii of all sizes that one could purchase as a donation (and leave behind to be prayed over) there were souvenir torii that a tacky tourist such as myself could purchase and for an extra couple of bucks could have inscribed with the date, one's name, and a proverb/prayer/quote of one's choice painted on it in script. "Safe travels" was my choice, and Yoshihiro Kimura (he had his own business card) painstakingly painted the symbols while he even more painstakingly tried to converse with me in English. One of my favorite souvenirs, it is now nailed to the lintel of my home office so that I pass under (through) it every day. Personally I think Adam's highlight was the icecream he bought when we returned to the rest stop. I had lemonade. Delicious.

There's definitely something more satisfying about having to put a little effort in. Had the avenue of torii only been a few yards the picture would have been exactly the same, but the lasting impression made by the journey up and down the mountain turned the adventure into something altogether more moving. Looking back at the end of our trip, this spontaneous addition to our agenda was one of our highlights. We retraced our steps to the bottom, and several hours later than we'd expected, bought two tickets at the little private railway station. Two minutes later a two-car train rattled into view and off we went to the north east end of town, and our next serendipedous surprise.

So the next stop was the Silver Pavilion. We had low expectations. It had a kind of symmetry with the Golden Pavilion, and it was convenient, but that's all it had going for it. As luck would have it, the route took us passed a restaurant with a huge octopus for a sign, waving it's tentacles. "Takoyaki" Adam says, "must be time for lunch." We watched the cook turning the little batter balls in their pan, which was set up in the window for that purpose. There was a choice of sauces but I couldn't really tell the difference. The balls were served at the temperature of molten lava, but the crisp fried outside, the chewy bite of the octopus pieces on the inside, a touch of vinegar from the mayonaise, and the smoky katsoubushi on the top were just world-class delicious. I washed it down with shochu, my new adult beverage of choice.

As you walk in through Ginkaku-ji's main entrance (left-most image above) the first thing you see is the (apparently) famous dry garden with its even more famous sand pile (middle and right-most images above). Compared to what we'd already seen, these did not move me in the same way, and I actually took the picture more for a record of the four gardeners who were all up in a tree pruning it leaf by leaf. They were taking the same care over a life-size tree as bonsaii lovers lavish over their pint-sized specimens. Also, as usual, it was tough getting an image of the sand that did it any kind of justice.

As you walk in through Ginkaku-ji's main entrance (left-most image above) the first thing you see is the (apparently) famous dry garden with its even more famous sand pile (middle and right-most images above). Compared to what we'd already seen, these did not move me in the same way, and I actually took the picture more for a record of the four gardeners who were all up in a tree pruning it leaf by leaf. They were taking the same care over a life-size tree as bonsaii lovers lavish over their pint-sized specimens. Also, as usual, it was tough getting an image of the sand that did it any kind of justice.

Ashikaga Yoshimasa initiated plans for creating a retirement villa and gardens as early as 1460 and after his death, Yoshimasa arranged for this property to become a Zen temple. It turns out the symmetry I imagined with the golden Kinkaku-ji is well-founded. Yoshimasa was the grandson of Ashikaga Yoshumitsu who commissioned Kinkaku-ji and this was to be a tribute to him. The two-storied Kannon is the main temple structure. Its construction began February 21, 1482. The structure's design sought to emulate Kinkaku-ji. It is popularly known as Ginkaku, the Silver Pavilion because of the initial plans to cover with a distinctive silver-foil overlay but this familiar nickname dates back only as far as the Edo period (1600–1868). Despite Yoshimasa's intention to cover the structure, this work was delayed for so long that the plans were never realized before Yoshimasa's death.

Even after 21st century restoration, there is still no silver foil used. After much discussion, it was decided to not refinish the lacquer to the original state. The lacquer finish was the source of the original silver appearance of the temple, with the reflection of silver water of the pond on the lacquer finish.

Even after 21st century restoration, there is still no silver foil used. After much discussion, it was decided to not refinish the lacquer to the original state. The lacquer finish was the source of the original silver appearance of the temple, with the reflection of silver water of the pond on the lacquer finish.

The present appearance of the structure is understood to be the same as when Yoshimasa himself last saw it. This unfinished appearance illustrates one of the aspects of "wabi-sabi" quality.

Like Kinkaku-ji, Ginkaku-ji was originally built to serve as a place of rest and solitude for the Shogun. During his reign as Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa inspired a new outpouring of traditional culture, which came to be known as Higashiyama Bunka (the Culture of the Eastern Mountain). The tea ceremony, Noh, flower arrangement and ink painting all acheived new levels of refinement here.

In 1485, Yoshimasa became a Zen Buddhist monk. After his death on January 27, 1490 the villa and gardens became a Buddhist temple complex, renamed Jishō-ji after Yoshimasa's Buddhist name.

In addition to the temple's famous building, the property features wooded grounds covered with a variety of mosses. One of these has-to-be-seen-to-be-believed moss gardens is captured here. We also saw gardeners picking out single strands of rogue grass that had dared to try to grow there. The Japanese garden, supposedly designed by the great landscape artist Sōami have undergone extensive restoration, started February 2008, and the Ginkaku-ji we visited was again in full glory. The sand garden of Ginkaku-ji has become particularly well known; and the carefully formed pile of sand which is said to symbolize Mount Fuji is an essential element in the garden. Well I'm not sure about the Mount Fuji symbol, it was not obvious to me. The angles were all wrong, or perhaps Fuji is more of a French curve to me, not this perfect trapezoid.

In addition to the temple's famous building, the property features wooded grounds covered with a variety of mosses. One of these has-to-be-seen-to-be-believed moss gardens is captured here. We also saw gardeners picking out single strands of rogue grass that had dared to try to grow there. The Japanese garden, supposedly designed by the great landscape artist Sōami have undergone extensive restoration, started February 2008, and the Ginkaku-ji we visited was again in full glory. The sand garden of Ginkaku-ji has become particularly well known; and the carefully formed pile of sand which is said to symbolize Mount Fuji is an essential element in the garden. Well I'm not sure about the Mount Fuji symbol, it was not obvious to me. The angles were all wrong, or perhaps Fuji is more of a French curve to me, not this perfect trapezoid.

What I am sure about is that we were both blown away by this garden, despite the fact that our normally infallable Eyewitness Guide claimed that some people found it overrated. In its defense it also says others call it an unequaled masterpiece. Take my word for it: whatever it was like before 2008, today it is an unequaled masterpiece. Small and exquisite, there was no particular spot like there was at Kinkaku-ji, but every step seemed to reveal another photo op.

Then it was time to find the Philosopher's Walk. The Philosopher's Walk. "One of Kyoto's best loved spots" it merits an entire page in the guide. How could it not be on our list? "A veritable promenade during cherry blossom and maple seasons." Well. Call me picky, but I've learned that I'm partial to there being water in my canals and other waterways. I don't necessarily need it to be moving, but if you can actually see the bottom, if it so dry you could walk along its bed, it seems to suck the beauty out of the scene. Lack of negative ions or something I guess. |

|

We trudged along, trying to imagine how much of a transformation the scraggly cherry trees could manage even in full bloom. Naturally the shops, restuarants, and art stalls that dotted the route all seemed to have closed up for the winter even though it was September and hot as hell.

We trudged along, trying to imagine how much of a transformation the scraggly cherry trees could manage even in full bloom. Naturally the shops, restuarants, and art stalls that dotted the route all seemed to have closed up for the winter even though it was September and hot as hell.

We wondered out loud whether the lack of tourists had shut the shops or the shut shops had stopped the tourists. Either way, the closed shutters only added to the depressing scene. The only thing open along the entire mile was two women sitting by the path selling post-card-sized water-colors out of a plastic supermarket bag. No good deed goes unpunished, as they say, and I'm pretty sure that the $1 or so I spend there was off-set by leaving them my prescription sun glasses.

We realized that if we hurried to the end, and treated ourselves to another cab, we could probably tack one more stop onto the agenda, which seemed a much more positive way to finish the sight-seeing portion of the day. So hurry we did, and lucky as ever quickly found a cab as soon as we returned to the nearest main street at the end of the walk.

We chose Sanjusangen-do as our extra stop. It was on the A-list, and was close enough to the town center that we knew we would not have to rely on there being buses to get home. To be more accurate, it was on my A-list. But when we got there, Adam realized it was not the one he was thinking of. Re-reading the guide, and thinking about his description, I suspect he was thinking of Ninna-ji or Nanzen-ji either or both of which sound worth a visit next time around.

Sanjūsangen-dō was originally built in 1164, and claims to the the longest wooden structure in the world (not to be confused with Higashi Hongan-ji which claims to be the largest wooden structure in the world). The temple name literally means Hall with thirty three spaces between columns, describing the architecture of the long main hall of the temple. The main deity of the temple is Sahasrabhuja-arya-avalokiteśvara or the Thousand Armed Kannon.

Sanjūsangen-dō was originally built in 1164, and claims to the the longest wooden structure in the world (not to be confused with Higashi Hongan-ji which claims to be the largest wooden structure in the world). The temple name literally means Hall with thirty three spaces between columns, describing the architecture of the long main hall of the temple. The main deity of the temple is Sahasrabhuja-arya-avalokiteśvara or the Thousand Armed Kannon.

The statue of the main deity was created by the Kamakura sculptor Tankei and is a National Treasure of Japan. But for us regular folks, for whom Eyewitness Travel Japan claims there is "an almost hallucinatory effect once inside its elongated main hall" the main attraction is the one thousand life-size statues of the Thousand Armed Kannon which stand on both the right and left sides of the main statue in 10 rows and 50 columns. Of these, 124 statues are from the original temple, rescued from the fire of 1249, while the remaining 876 statues were constructed in the 13th century. The statues are made of Japanese cypress. Around the 1000 Kannon statues stand 28 statues of guardian deities.

When it says elongated, it's not kidding. In this photo, taken at one end, the portal jutting out in the distance is not the other end, it is at the half-way point.

When it says hallucinatory, it is close, but I would add creepy to that. Not for the first time, we could not take photographs, so these images are stolen from the interweb. The left image below (I'm certain taken from the half way point looking to one end) is indeed closer to the hallucination state. But what we saw was closer to the right hand image, which I think you'll agree is closer to creepy. I have no idea what it takes to get from one to the other. Perhaps they are cleaned occassionally? Anyway, an unforgettable image, even if one would actually be somewhat relieved to be relieved of the memory.

When it says hallucinatory, it is close, but I would add creepy to that. Not for the first time, we could not take photographs, so these images are stolen from the interweb. The left image below (I'm certain taken from the half way point looking to one end) is indeed closer to the hallucination state. But what we saw was closer to the right hand image, which I think you'll agree is closer to creepy. I have no idea what it takes to get from one to the other. Perhaps they are cleaned occassionally? Anyway, an unforgettable image, even if one would actually be somewhat relieved to be relieved of the memory.

As we came out, the sun was starting to set. Standing on the same spot the main temple picture was taken, I turned to the other side of the court yard and caught this anonymous building in the evening light.

We started to walk back into town.We paused a couple of minutes to snap this traditional house in the last rays of the afternoon sun, then hopped a bus for a couple of stops with our day passes, and arrived back at the hotel at nightfall. Usual routine: shower, change, figure out where to eat. Our friendly concierge/desk clerk recommended a yakatori place across town where we'd get an authentic experience, and everything on the menu, including drinks were all the same price, about $2.00 a pop. All we had to do was find it.

We started to walk back into town.We paused a couple of minutes to snap this traditional house in the last rays of the afternoon sun, then hopped a bus for a couple of stops with our day passes, and arrived back at the hotel at nightfall. Usual routine: shower, change, figure out where to eat. Our friendly concierge/desk clerk recommended a yakatori place across town where we'd get an authentic experience, and everything on the menu, including drinks were all the same price, about $2.00 a pop. All we had to do was find it.

The usual couple of mile walk, then some wandering around, and finally someone was able to point at it. Not for the first time, we'd been caught by what we called the third dimension: what was happening at street level often had absolutely nothing to do with what was happening on the second or third floor, or as high as the seventh floor in this case. We took the rickety two person 'vator to the top, and it opened into a different universe. Rustic tables, benches and stools, saw dust on the floor, and the level of laughter and chatter I would normally associate with a lively bar. Which I guess this was, if the drinks really were $2 each. As the doors opened, the entire staff shouted a welcome in unison, and someone came over and guided us to a couple of stools together right in front of the cook. She was turning the yakatori skewers on a little hibachi grill. It was non-stop work. After an hour or so one of the waiters took over and "our" cook returned to serving tables. Excellent. And everything really was $2. 12 pairs of sticks, 6 beers, 2 shots, $40. Great night.

We tried to get a bus home. We always figured it was easier to get a bus into town that to risk one coming out, which could end up who-knows-where. But none of the buses seemed bound for the railway station and when we finally found one heading roughly the right direction, after one more stop incredibly it did a u-turn and left us futher away from home than when we'd got on it. We walked home, after which we were too tired for a night cap. Since it was only about 10:30pm the front door was unlocked, and our buddy was still on duty. We chatted about our plans for the morning. Since we were leaving before he came on duty, he gave us the gift he'd planned for a leaving present: a pair of chop-sticks each. "Made in Japan, not made in China" he said emphatically. He was then even more enthusiastic about visiting Himeji on our way back from Hiroshima. Even though, yes, it had a huge shed over it like the one over Nishi, he said this was good, and we needed to reserve "birds-eye" tickets. We knew a gift horse when we saw it, so we got him to help us to make the reservation on the lobby computer. We had no idea what we were buying, but that's what serendipity is all about. With that, Kyoto was done, and we crashed.

It took us a while, because every photo op needs to be recorded, but eventually we were done, and we found ourselves on the street again, which was lined with small stalls that all seemed a somewhat classier than the average tourist trap. I bought pickles from a woman who was only selling pickles, and a bottle of ramune because I was intrigued by the bottle, but in fact the cider itself was excellent and perhaps more important at that moment, thirst-quenching. Finally, I could not resist a wheel of Baumkuchen (green tea flavor no less) because it was crazy to see it here so far from its home, and amusing that it was actually called Baumkuchen, even in Japanese.

It took us a while, because every photo op needs to be recorded, but eventually we were done, and we found ourselves on the street again, which was lined with small stalls that all seemed a somewhat classier than the average tourist trap. I bought pickles from a woman who was only selling pickles, and a bottle of ramune because I was intrigued by the bottle, but in fact the cider itself was excellent and perhaps more important at that moment, thirst-quenching. Finally, I could not resist a wheel of Baumkuchen (green tea flavor no less) because it was crazy to see it here so far from its home, and amusing that it was actually called Baumkuchen, even in Japanese.