Culture and History

One of the less important goals on my bucket list is to visit all seven continents. But checking off "Asia" as a result of this trip to Japan did not seem right. Keen as I was to visit, part of what I looked forward to was that there would not be the same culture shock as some of the previous trips—several of which had been to places where we couldn't even drink the water. Pictures of modern Japan by contrast showed just that: a modern, western-standard world with roads, phones, power, wealth, fashion, and yes, sufficient drinking water that it is even flushed down the toilet. So what a fascinating additional challenge it was to find myself almost continuously thrown off kilter by the non-stop stream of events large and small that were strange, surprising, or both, and/or which I just can't imagine experiencing anywhere else but which somehow do seem to add to the picture of who these fascinating people are. I've gathered some of them here, with nothing in common other than they didn't fit into the story-thread of the travelogue (which is seriously long enough already) but which were fun enough for me to record. I loved them all.

- Pop Culture

- Respect for personal space

- Pachinko

- Jiro Dreams Of Sushi

- Nihon Sankei

- Shinto or Buddist?

- Only in Japan

- Bars and Drinking

- History

One of the things I most enjoy about researching a trip is when it clarifies or explains observations made on the ground. Of course it would have been better to have made the connections before the trip, but you can't win them all. This blog is full of such observations, but this one was a true "Aha!" moment, and one that frankly, had I put all the pieces together in advance would not have had nearly the same impact. So, the first thing that's important to know is that my first introduction to regular folks on the street was when we exited the station at Shibuya Crossing.

One of the things I most enjoy about researching a trip is when it clarifies or explains observations made on the ground. Of course it would have been better to have made the connections before the trip, but you can't win them all. This blog is full of such observations, but this one was a true "Aha!" moment, and one that frankly, had I put all the pieces together in advance would not have had nearly the same impact. So, the first thing that's important to know is that my first introduction to regular folks on the street was when we exited the station at Shibuya Crossing.

It was hard not to stare at the teeming throngs of trendy young things. Dressing decisions for each body section seem to be made independently of one another. Sandy-brown dress shoes were popular with guys, but could be worn with suits of any color—or shorts. Women's shoes could be from flat to 4 or 5 inch platforms. Again even a pair of clunky-looking gothic-come-Doc Martins with 2 inch platforms were under a pin-stripe suit with shorts. Skirts were either mini or looser to-the-knee jobs. A popular variant of this latter style was school-girl. Dark pleated skirt, crisp white blouse and knee-highs. Adam thought they probably were school-girls. But what were they doing in uniform at 8pm on a Sunday night?

Some mini skirts came with socks/stockings that came half way up the thigh but always stopped 3 or 4 inches below the skirt. Conspicuously absent were jeans (even long pants were fairly rare) except occasionally on a guy. If they wore shorts they were invariably below the knee for guys, and short short short for women. Also absent sandals, rips, tears, or any other dishevelled sort of choice. The overall effect was of extreme individuality, but somehow a lack of overall style, or class? Perhaps, but it was fun, and the lack of conformity was down-right refreshing. With the exception of the school girl uniforms, no two people were wearing anything close to the same thing. But also if not exactly provocative, there was a definite stamp of femininity, a starker contrast between male and female styles.

|

Then six months after the trip I was searching Google's image library and what I'd asked for threw up a bunch of images from Japanese comic books and anime, in my defense neither of which were something I pay much attention to. But the connection slapped me right in the face. I was looking at the trendy young things at Shibuya. It was amazing actually: the scantily clad female characters with the gigantic breasts of cartoon women, but the huge eyes and button noses of cartoon children had somehow been replicated perfectly by the trendy young things in a fascinating real-life homage. Back to Shibuya: even my trusty Eyewitness Travel explains that why it is a must visit attraction is that "Shibuya is the sakariba (party town) for Tokyo's youth. It has been so since the 1930's, [ ... and is ..] the place to see the latest in fashion ..." That explains absolutely everything, from why I felt so old there, to why Shibuya felt like the epicenter, and although we saw these trends everywhere, the further away we got, the more frequently we saw more mainstream styles, such as jeans, skirts or even kimonos. |

Although we worked hard to control the crowds (visiting in the off season, travelling in off times, seeking out activities off the beaten path) we were intensely aware of the population density. I was curious to see a sign on the subway platform floor indicating that at certain times of day the cars that stopped here were for women only. Really? They have a gropping problem in this intensely reserved, polite society? The train pulled in, I got on, and even though Adam was right behind me, it was not clear that he would be able to get on. No problem. As the doors were about to close it was as if we took a collective breath and the crowd suddenly compressed. This was several hours after rush hour, and we were so tightly locked together that if I could move my fingers I certainly couldn't move my hands, and my arms were locked into position like one of these casts of Pompeii victims. Whatever my anatomy was doing, wherever parts of someone else they were pressed against they were there until the next stop. Holy shit, it was intimidating enough as an old guy, never mind a young woman.

But this brings us to the next point: the emphasis on bathing. Americans think Europeans don't bathe enough, but the fact that every hotel no matter how cheap, made it clear by the emphasis on their baths, and the clean cloths they provided for you to change into afterwards, that this was a different standard again. And on that subway it paid off: at least we were not assaulting each other's senses.

Riding the subway a significant number of people are studying their portable devices, just like anywhere else. But we never once were able to hear any of them. If you shut your eyes you would have no idea you were within 20 feet of a dozen of them. When a cell phone went off on the Shinkansen one day, the culprit looked like he'd been caught shop-lifting and he rushed out of the carriage trying to stifle the noise. Perhaps the best example of all was the lounge floor in the module hotel, with two televisions on the wall perhaps 10 feet apart. They were tuned to different channels, but the sound was turned so low that you could watch one and not the other, or tune out both of them if you were simply reading/snoozing.

Lastly, in the module hotel, there are twenty or thirty other folks in the room, and each module had a curtain for a front door. Not only did folks leave their luggage on their beds when they left for the day, but at night every wall socket was a Christmas tree of unattended smart phones plugged in to recharge.

I can't pronounce even the simplest things because it appears to be impossible to utter any word without stressing any of the syllables. It makes such a difference that often as not when they pronnounce the word I don't even recognize it. But even knowing the rules, I don't seem to be able to make my mouth do the right thing.

Words fail me. A pachinko parlour is the Japanese equivalent of a slot arcade. That's about where the similarity ends. They were very common in big cities, and always had a big glass store front, like a regular store. The glass did a good deal of soundproofing, because when I opened the door, my first reaction was to let it swing shut again. The deafening barrage of noise, and smoke so thick I needed a machete to chop a path through it gave me no enthusiasm to proceed any further, but Adam shoved me inside.

|

A pachinko machine is a cross between a one-armed bandit and a pinball machine. The ammunition is steel marbles, which players can control projection velocity for, then all they can do was watch it tumble back to the bottom, hopefully hitting a good number of winning ostacles along the way. Hence pachin the sound of the bouncing ko, ball. The clanging and banging of the balls bouncing earthward in all the machines was only part of the noise. Each machine was playing music or a video, and more music from overhead speakers tried to drown all the other sources. "Apparently," Adam shouted over the cacophany, "people come in here to relax." |

|

Flourescent lighting overhead, and of course each machine constantly flashing its "pick me! pick me!" lights made me wonder how often it triggered epilepsy.

Best of all, gambling is illegal in Japan. So most people are playing for ... yes, more steel marbles, which come crashing out of the machine so regularly that everyone has spare buckets at their side in case they need one quickly to catch the spill. You can actually cash in the trays for alcohol or stuffed animals and the like, but if you really insist on a cash pay out, then they will give you plastic tokens that you can finally exchange for cash in a different store up the street. By disconnecting the cash winnings from the actual sport in this way, it appears that it does not count as gambling, at least as defined by the Japanese legal defination.

I probably lasted about 60 seconds before I had to run screaming from the room. I describe it here, a) because it haunts me still, b) because it represents the absolute opposite of everything that I loved about Japan, c) because it's a mystery: why, despite b) does it seem to be so quintessentially Japanese?

"Jiro Dreams Of Sushi" is a highly recommended documentary about the legendary sushi master Jiro Ono whose sushi restaurant in Tokyo's Ginza Tokyo subway station is the only restaurant in Japan with a Michelin Three Star rating. It looks as if it was made ten or fifteen years ago, (the video definition is not great) but it provides a fascinating insight into a Japanese way of thinking, which I think explains a lot about why it feels so different there. For example, Jiro is constantly talking about quality and consistency, which to be fair, is one of the things that Michelin rates on: is every dish of the same quality, are they all the same high quality day in, day out, month in, month out? Some times this plays out understandably: merchants at the Tsukiji tuna market will hold a fish back "because only Jiro appreciates the quality" but it is harder for me to get my head around his son Yoshikazu who is now in his 50's has worked in the restaurant all his life, but claims he "couldn't possibly make sushi as good as Jiro does, because he has 30 more years experience." It takes Jiro 10 years to train an apprentice. One of them explained he'd made egg sushi every day for four months before Jiro finally announced "this one is okay." Jiro literally dreams of sushi. He takes national holidays off, but otherwise is at the restaurant all day every day. Every day looks exactly like the one before, and the one after, which is just what he likes. His other son, on his father's instruction, opened a second restaurant. Because he is left-handed, although it otherwise looks exactly the same as the first restaurant, the entire place is a mirror image of the original. The fanatical attention to detail, and detail at every level, is mind-numbing. It reminds me of another story I heard where some imported product was rejected by the retailer because they didn't like how scruffily the items were shrink-wrapped.

This repetition, which gives one the impression of mindless obedience, is in fact a concious, calculated effort to create consistent quality, and it was evident everywhere, but my favorite other example was the train driver who made this pointing jesture with his white-gloved index finger as we approached every signal. With a little nod he was obviously obeying his training, but he was also making himself conciously aware of the fact that he had seen the signal, and acknowledged its message.

Everyone keeps lists, and the Japanese are no different. Three most beautiful gardens, top five temples in Kyoto, and so on and so on. Miyajima the island off the coast as Hiroshima where we visited the Itsukushima Shrine is on perhaps the most famous list of all, the Three Most Scenic Places in Japan. What makes this list so fascinating to me is that it was created in the first half of the 17th century by a Confucian scholar, Shunsai Hayashi, and has remained unchanged and undisputed ever since. He wrote a book based on his experiences as he traveled throughout Japan on foot. In the book, "Nihon Kokujisekikou" ("Observations About the Remains of Japan's Civil Affairs"), he bestowed his unqualified praise on the three locations in Japan he thought offered travelers the most scenic beauty in the nation. The scenic masterpieces of Matsushima, Amanohashidate, and Miyajima. I don't doubt that they are spectacular (Miyajima certainly is) and who is to say that the fact that they are as spectacular today as they were in the Edo period may in part be because they are on the list. I guess it doesn't matter. They are still being enjoyed, and that's a good thing. I just mention it because it seems to say something about the people and the culture that it has endured so well, for so long.

To the uninitiated, (that would be me for a start) these two religions are hard to tell apart, but given how much of our time was spent visiting one or the other's sites, it seems right to at least attempt to do so. Torii and shimenawa (twisted rice-straw ropes) are Shinto. Anything -ji is Buddhist. Shrines: Shinto. Temples: Buddhist. Charms and votive tablets for sale: Shinto. Jizo statues with their red bibs and caps: Buddhist.

Shinto is the natural spiritual cult of Japan. Literally "the way of the Gods" Shinto was originally adopted from ancient Chinese inscriptions. On the other hand, Buddhism is a tradition envisaged as the ultimate path of salvation which is to be achieved through an imminent approach into the absolute nature of reality and existence.

Shinto is a unique religion where the ritual practices, actions and rites are a lot more significant than the words or preaching. On the other hand, Buddhism is a religion that does not recognize many religious rites or practices. It primarily focuses on the relation and study of the words and philosophies of the Buddha and the paths of existence as showed by him.

Shinto exemplifies the worship of the abstract forces of nature, the ancestors, nature, polytheism, and animism. The central focus remains on ritual purity which revolves around the honoring and celebration of the existence of Kami which is the ultimate spirit of essence. In a differing way, the foundation of Buddhism lies on the performing of altruism and following the paths of ethical conduct. Some of the common practices of Buddhism are cultivation of wisdom through meditation and renunciation, invocating the bodhisattvas and studying the scriptures.

Summary:

1. Shinto is an ancient religion from Japan whereas Buddhism is a tradition envisaged in India by Siddhartha Gautama.

3. Shinto lays importance to religious actions and rites rather than words and preaching whereas the foundation of Buddhism is the words and preaching of Buddha. Buddhism focuses on an altruistic life that leads to salvation.

5. Shinto worships the forces of nature, polytheism and animism whereas Buddhism is all about following an ethical code of conduct in one’s life and practice meditation and renunciation.

According to wikipedia, a 2008 survey showed 39% of Japanese reporting some sort of religious belief. Of those, 34% declared following Buddhism, compared to 3% Shinto. Figures that state 84% to 96% of Japanese adhere to Shinto and Buddhism are not based on self-identification but come primarily from birth records, following a longstanding practice of officially associating a family line with a local Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine.

A random collection of pictures and one-paragraph observations."We are not in Kansas anymore Toto." "No Dorothy, we're in Japan."

|

The number of names for the same thing could be truly baffling. The Golden Pavilion is actually called Kinkaku-ji, except that's not really true either because its formal name is Rokuon. Senso-Ji is also known as Asakusa Kannon. Sugidama the dried leaf balls hanging outside sake breweries are also known as sakabayashi. A name may or may not be hypenated. Ryoanji or Ryoan-ji? Shachi-gawara or shachi; bakamatsu or bakufu. My totally unresearched theory is that when your written language is so ambiguous that all but the simplest messages need to be interpreted to decypher the most likely meaning, (it is like listening to a fortune-teller reading the tea leaves), it does not seem a stretch that names would also be ambiguous, especially as often the name is some sort of description. Nakasendo means road through the central mountains, Shinkansen means New Trunk Line. So everything is a story, and the story start with kanji, the logographic Japanese writing system. It seemed to me that even the kanji itself could not be relied on. I was delighted when Adam pointed out to me that To-kyo and Kyo-to were the same pair of syllables and so the kanji was two symbols reversed. But when we got to Kyoto this no longer seemed to be true. While we are on the subject of language, Japan is not alone in liking to use English (or perhaps I should just say "western") words to name things, but the results are just as delightful: Ciaopanic clothing store, "Too Sweet Ass" (a bar we visited several times in Shibuya), and what appeared to be an advertizement for a restaurant called Love & Joy, with the byline "Powered by Miso Soup." In Nagoya, where we spent time in the car, listening to the radio, the ads were a constant barrage of advice about how to behave "for the safety" and for economy (not accelerating and breaking hard for example). On the highway we were passed by a police cruiser, and it was impossible not to notice that the troopers (or whatever they are called) were wearing helmets inside the car. In other (safe) news, a common sight when cars and pedestrians have to share space (sidewalk under repair, cars emerging from parking garages) was a crossing guard, who invariably looked like a Christmas Tree, no exaggeration. One smaller old man was so covered in (blinking) lights, reflectors and flourescent bands that it was almost impossible to see the (orange) jacket he was wearing underneath. He even had those orange illuminated batons aircraft ground handlers use in each hand, also flashing. |

Okay, Japan counts as Asia. Continent 5. |

Another personal wild theory attempts to answer our frequent observation that the Japanese appear to have the same distaste for being mistaken for Chinese that Canadians have for the assumption that they are American. It's not hatred, but it is still a strongly stated aversion, especially for such an otherwise non-confrontational people. And yet everywhere we went things were influenced by Chinese painters, poets, landscape, you name it. Even Shinto, the local religion was adopted from China. On reflection, it seemed as if the favorable stuff is all historical, the negative stuff is Meiji and beyond. Displaying my ignorance in full, it was only while researching my history for the more accurate piece below on the remarkable 19th century transformation of Japanese society that I discovered the first SinoChinese War (1894) and probably more particularly the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) one or both of which would seem extremely likely candidates to explain the phenomenon.

"Go away and come back yesterday." = You are an idiot. Putter golf: 9 or 18 holes, but no fairways. Chip shot to the green, then putt. Come to think of it, that's not such a bad idea. For a start, it could be played in a much more reasonable amount of time. While we're on space-restricted golf, you can't beat a two-storey driving range for square foot bang-for-the-buck. |

It's just not a western bike. Are the wheels even different sizes or is that an optical illusion? |

|

|

"Happou bejin" Eight-faced smiling person. (I can't corroborate this). The Japanese equivalent of "two-faced" but in Japan you can have eight different faces. Some of these additional faces were doubtless required for the additional characteristic of a happou bejin namely that of being a yes-man. A truly slippery customer.

"Happou bejin" Eight-faced smiling person. (I can't corroborate this). The Japanese equivalent of "two-faced" but in Japan you can have eight different faces. Some of these additional faces were doubtless required for the additional characteristic of a happou bejin namely that of being a yes-man. A truly slippery customer.

This sign on a telephone pole is typical of a style we saw all over the place, from bus tickets, to, well, NIppon Telephone and Telegraph warnings. Any sort of "generic" customer information as opposed to advertizing or marketing. This one I liked in particular not least because it reminds me so much of "Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel" but also because it is so understandable and effective. It even says it's not just any cable, it's a telephone cable. But like the pop culture and the anime, it also seems to speak of a less cynical, I would even go so far as to say less aggressive way of thinking. Not "10 billion volts!!! Touch this and die!!!" more of a "Hey, we've got stuff we care about buried here. Please do try to be careful and avoid damaging it if you can."

Exactly the culture that has a shop assistant use both hands to offer up a tray to you for you to put your money in so that you do not have to touch, or even both have hold of it simultaneously, for even a brief second. I assume this has something to do with avoiding the appearance of dragging the money from the customer, and instead the willing customer proffers it up and having left it for you, you are then free to collect it. And then count the change back out into the tray so that in turn you can retrieve it.

Wheat iced tea. Tastes like grass. Surprise.

"Be mindful of others with rolling luggage." I also saw an item on a TV news magazine show where the reporter tried to take a stroller on a subway train. Message: do not be so antisocial! They are a struggle for you and inconvenient for other passengers. It made me realize how few strollers I saw. I asked Alistair about it: "no, as soon as you can walk, you walk." For every one stroller we saw, we must have seen 50 toddlers and beyond trotting along with their parents. A staggering number of them had backpacks on.

'Nuff said |

"I hope you drank the slops in the box: it was a gift." Oh yeah. |

Harvesting rice. Right next to a crop that is just sprouting. |

The attention to detail, pride, cleanliness, service is world reknown, but you don't fully appreciate what that means until you experience it. In the Post Office, the clerk would not let us lick the stamps we just bought. We were asked to hand over our envelopes and post cards, and she licked and placed the stamps for us. One day in a latrine (never pass a servicable laterine) the attendent was on his hands and knees, scrubbing out the urinal trough. There is no such thing as an unbussed table, and the Shinkansen was cleaned and wiped each time it turned around, not that there was ever any litter to pick up. Heck, even the garbage piles on the street were neat. Even the trash carts were so clean and polished you could see your reflection in the hubcaps, which on most trucks were chromium-plated, so a good shine could be had.

The attention to detail, pride, cleanliness, service is world reknown, but you don't fully appreciate what that means until you experience it. In the Post Office, the clerk would not let us lick the stamps we just bought. We were asked to hand over our envelopes and post cards, and she licked and placed the stamps for us. One day in a latrine (never pass a servicable laterine) the attendent was on his hands and knees, scrubbing out the urinal trough. There is no such thing as an unbussed table, and the Shinkansen was cleaned and wiped each time it turned around, not that there was ever any litter to pick up. Heck, even the garbage piles on the street were neat. Even the trash carts were so clean and polished you could see your reflection in the hubcaps, which on most trucks were chromium-plated, so a good shine could be had.

In the supermarket you could buy four slices of bread. Or six, or eight. After that you had to buy a whole loaf.

And last but by no means least, I kid you not, we passed by a drive thru telephone ... telephone what? Kiosk isn't the right word if you can get a car into it, surely? And how did it work? I imagined a 1960s, American Graffiti sort of scenario, with a cross between a hotel clerk and those chicks on roller-skates serving customers at the drive in, only they have a phone on a long cord balanced on their little trays. Obviously long deceased, no one had the faintest clue how it might have worked. Even the interweb seems to be stumped.

With the notable exception of the British Pub in Nagoya, the most conspicuous characteristic of all the bars we went to was that they were tiny. In turn this meant that even if the bar was crowded, at most that meant there were perhaps a dozen patrons, and so one never lost the sense of personal service. Every time you ordered a drink there was a process, some ceremony, a ritual that needed to be performed, whether it was refreshing the dish of pickles, or chipping a new block of ice so that it was small enough to slip into the glass, the polishing of the glass, or the careful placement in front of you of a selection of options. It made the experience more like being in a top flight restaurant, leaving "regular" bars to be compared instead to a fast food joint.

With the notable exception of the British Pub in Nagoya, the most conspicuous characteristic of all the bars we went to was that they were tiny. In turn this meant that even if the bar was crowded, at most that meant there were perhaps a dozen patrons, and so one never lost the sense of personal service. Every time you ordered a drink there was a process, some ceremony, a ritual that needed to be performed, whether it was refreshing the dish of pickles, or chipping a new block of ice so that it was small enough to slip into the glass, the polishing of the glass, or the careful placement in front of you of a selection of options. It made the experience more like being in a top flight restaurant, leaving "regular" bars to be compared instead to a fast food joint.

When drinking in company (and therefore more likely to have ordered a whole bottle of something), common courtesy is that you never serve yourself: You may serve everyone else, but then one of them should serve you. The one exception is shōchū which is commonly regarded as a hassle to serve, because it typically involves ice, water, or both. In this case, the youngest or most junior-ranked person does the serving and "because everyone (else) is drunk by now" is allowed to serve himself also. (I think this rule is male-oriented/biased.)

The bar illustrated here was a stand out in that it was a genuine top flight experience. For every day use I prefer something a little more earthy, but this is the one I will remember the longest and which deserves the attention here. No surprise that we were brought here by Adam's friends Alistair and Maiko-chan, we'd never have known to look for it, never mind find it, on the seventh floor of its building. We also needed to make a reservation. It specialised in Japanese and Scotch whisky. The waiter looked, moved, and dressed like Pee-wee Herman, but he knew his single malts. Always one open to be surprised, I needed to try the Japanese options, but I was not optimistic. While many new-fangled places (Massachusetts to name one purely at random) are doing an excellent job with their own gins, I'd never found a single malt from anywhere outside its Celtic Scotland/Eireland origins that was anything other than just plain terrible. Alistair and Pee-wee took on the challenge with gless, and agreed on Nikka Taketsuru 17 Year Old.

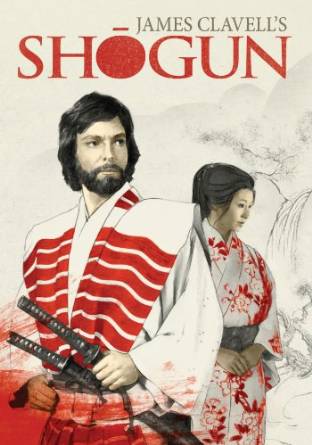

Most of what I knew about Japanese culture and history was based on watching that great early 1980’s TV mini-series, Shogun, James Clavell’s saga of an English adventurer in 16th century Japan. I was deeply influenced by the stunning beauty of the people, the clothes, the architecture and the gardens. Everything. But the nagging thing then, and really up until now, was a mismatch, a break in the time-space continuum. Fact or fiction, Japan either seemed to be represented as a mediaeval feudal society, or as a 20th century society rivaling even the most modern Western countries. There was no in-between. One minute feudal, the next 20th century. Could that really be? How? When did it happen?

Most of what I knew about Japanese culture and history was based on watching that great early 1980’s TV mini-series, Shogun, James Clavell’s saga of an English adventurer in 16th century Japan. I was deeply influenced by the stunning beauty of the people, the clothes, the architecture and the gardens. Everything. But the nagging thing then, and really up until now, was a mismatch, a break in the time-space continuum. Fact or fiction, Japan either seemed to be represented as a mediaeval feudal society, or as a 20th century society rivaling even the most modern Western countries. There was no in-between. One minute feudal, the next 20th century. Could that really be? How? When did it happen?

Short answer: yes. Basically between 1853 and 1867 Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as sakoku and changed from the Edo feudal shogunate Bakumatsu (幕末) to the Meiji government. This late Tokugawa Shogunate literally means "end of the curtain". There is a great article on this in Wikipedia (of course) but here’s my synopsis.

From the beginning of the 19th century, whaling and trade with China significantly increased the number of western ships in Japanese waters. It was hoped that Japan could become a base for supply or at least a place where shipwrecks could receive assistance. Frictions with foreign shipping and in particular violent demands made by the British frigate Phaeton in 1808 led Japan to take defensive action. In 1825, the Bakumatsu issued an Edict to expel foreigners at all cost, prohibiting any contacts with foreigners. It remained in place until 1842.

After the victory of the British over the Chinese in the 1840 Opium War, many Japanese realized that traditional ways would not be sufficient to repel Western intrusions, but when Commodore Matthew C. Perry's four-ship squadron appeared in Edo (Tokyo) Bay in July 1853, the Bakumatsu was thrown into turmoil. Commodore Perry was fully prepared for hostilities if his negotiations failed, and to demonstrate his weapons, Perry ordered his ships to attack several buildings around the harbor.

The American fleet returned in 1854. The chairman of the senior councillors, Abe Masahiro, tried to balance the desires of the senior councillors to compromise with the foreigners, of the emperor who wanted to keep the foreigners out, and of the feudal daimyo rulers who wanted to go to war. Lacking consensus, Abe compromised by accepting Perry's demands for opening Japan to foreign trade while also making military preparations. In March 1854, the Treaty of Peace and Amity (or Treaty of Kanagawa) maintained the prohibition on trade but opened the ports of Nagasaki, Shimoda and Hakodate to American whaling ships seeking provisions, guaranteed good treatment to shipwrecked American sailors, and allowed a United States consul to take up residence in Japan.

The American fleet returned in 1854. The chairman of the senior councillors, Abe Masahiro, tried to balance the desires of the senior councillors to compromise with the foreigners, of the emperor who wanted to keep the foreigners out, and of the feudal daimyo rulers who wanted to go to war. Lacking consensus, Abe compromised by accepting Perry's demands for opening Japan to foreign trade while also making military preparations. In March 1854, the Treaty of Peace and Amity (or Treaty of Kanagawa) maintained the prohibition on trade but opened the ports of Nagasaki, Shimoda and Hakodate to American whaling ships seeking provisions, guaranteed good treatment to shipwrecked American sailors, and allowed a United States consul to take up residence in Japan.

Townsend Harris, the first U.S. Consul, persuaded the Japanese to sign the "Treaty of Amity and Commerce" by pointing out that the aggressive colonialism of France and Great Britain against China in the current Second Opium War (1856–1860), suggested that these countries would not hesitate to go to war against Japan as well, and that the United States offered a peaceful alternative. An important point of the Treaty was that the ports at Edo, Kobe, Nagasaki, Niigata, and Yokohama were opened to foreign trade.

The opening of Japan to uncontrolled foreign trade brought massive economic instability. While some entrepreneurs prospered, many others went bankrupt. Unemployment rose, as well as inflation. Coincidentally, major famines also increased the price of food drastically. Foreigners also brought cholera to Japan, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths.

During the 1860s, peasant uprisings and urban disturbances multiplied. Several missions were sent abroad by the Bakumatsu, in order to learn about Western civilization, revise unequal treaties, and delay the opening of cities and harbour to foreign trade. These efforts towards revision remained largely unsuccessful. A Japanese Embassy to the United States was sent in 1860 and a First Japanese Embassy to Europe was sent in 1862.

Belligerent opposition to Western influence further erupted into open conflict when the Emperor Kōmei, breaking with centuries of imperial tradition, began to take an active role in matters of state and in the spring of 1863 issued his "Order to expel barbarians". The Shimonoseki-based Chōshū clan, under Lord Mori Takachika, followed on the Order, and began to take actions to expel all foreigners. Openly defying the shogunate, Takachika ordered his forces to fire without warning on all foreign ships traversing Shimonoseki Strait.

A Second Japanese Embassy to Europe was sent in December 1863, with the mission to obtain European support to reinstate Japan's former closure to foreign trade, and especially stop foreign access to the harbor of Yokohama. The Embassy ended in total failure as European powers did not see any advantages in yielding to its demands.

Western nations planned an armed retaliation against the Chōshū clan with the Bombardment of Shimonoseki, which occurred in September 1864. This conflict threatened to involve America, which in 1864, was already torn by its own civil war. Following these successes against the imperial movement in Japan, the Bakumatsu was able to reassert a certain level of primacy at the end of 1864.

The military interventions by foreign powers also proved that Japan was no military match against the West, and that expelling foreigners was not a realistic policy. The structural weaknesses of the Bakumatsu however remained an issue, and the focus of opposition then shifted to creating a strong government under a single authority.

As the Bakumatsu proved incapable to pay the $3,000,000 indemnity demanded by foreign nations for the intervention at Shimonoseki, foreign nations agreed to reduce the amount in exchange for a ratification of the Harris Treaty by the Emperor, a lowering of customs tariffs to a uniform 5%, and the opening of the harbours of Hyōgo (modern Kōbe) and Osaka to foreign trade.

The Bakumatsu led a second punitive expedition against Chōshū from June 1866, but the Bakumatsu was actually defeated by the more modern and better organized troops of Chōshū. The new Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu (aka Keiki) managed to negotiate a ceasefire due to the death of the previous Shogun, but the prestige of the Shogunate was nevertheless seriously affected. This reversal encouraged the Bakumatsu to take drastic steps towards modernization.

Naval students were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years, starting a tradition of foreign-educated future leaders, such as Admiral Enomoto. By the end of the Bakumatsu in 1868, the Japanese navy of the shogun already possessed eight western-style steam warships, which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin war, under the command of Admiral Enomoto. A French Military Mission to Japan (1867) was established to help modernize the armies of the Bakumatsu. Japan participated in the 1867 World Fair in Paris.

Naval students were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years, starting a tradition of foreign-educated future leaders, such as Admiral Enomoto. By the end of the Bakumatsu in 1868, the Japanese navy of the shogun already possessed eight western-style steam warships, which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin war, under the command of Admiral Enomoto. A French Military Mission to Japan (1867) was established to help modernize the armies of the Bakumatsu. Japan participated in the 1867 World Fair in Paris.

Keiki reluctantly became head of the Tokugawa house and shogun following the unexpected death of Tokugawa Iemochi in mid-1866. In 1867, Emperor Kōmei died and was succeeded by his second son, Mutsuhito, as Emperor Meiji (left). Keiki tried to reorganize the government under the Emperor while preserving the shogun's leadership role. Fearing the growing power of the Satsuma and Chōshū daimyo, other daimyo called for returning the shogun's political power to the emperor and a council of daimyo chaired by the former Tokugawa shogun. With the threat of an imminent Satsuma-Chōshū led military action, Keiki moved pre-emptively by surrendering some of his previous authority.

After Keiki had temporarily avoided the growing conflict, anti-shogunal forces instigated widespread turmoil in the streets of Edo using groups of rōnin. Satsuma and Chōshū forces then moved on Kyoto in force, pressuring the Imperial Court for a conclusive edict demolishing the shogunate. Following a conference of daimyo, the Imperial Court issued such an edict, removing the power of the Bakumatsu shogunate in the dying days of 1867. The Satsuma, Chōshū, and other han leaders and radical courtiers, however, rebelled, seized the imperial palace, and announced their own restoration on January 3, 1868. Keiki nominally accepted the plan, retiring from the Imperial Court to Osaka at the same time as resigning as shogun. Fearing a feigned concession of the shogunal power to consolidate power, the dispute continued until culminating in a military confrontation between Keiki and allied domains with Satsuma, Tosa and Chōshū forces, in Fushimi and Toba. With the turning of the battle toward these anti-shogunal forces, Keiki then quit Osaka for Edo, essentially ending both the power of the Tokugawa, and the shogunate that had ruled Japan for over 250 years.

But the weirdest part was that although Miss Marple would have found many of the choices shocking, for some reason there was nothing provocative about it. It seemed too innocent, like little girls dressing up as women.

But the weirdest part was that although Miss Marple would have found many of the choices shocking, for some reason there was nothing provocative about it. It seemed too innocent, like little girls dressing up as women.

There is a video simulation game where you are a Shinkansen driver, and the object of the game is to keep as closely as you can to the timetable.

There is a video simulation game where you are a Shinkansen driver, and the object of the game is to keep as closely as you can to the timetable.