Nakasendō 中山道

The Nakasendo was actually on my radar a long time before Japan as a destination became a real target. I'd been looking for other long distance walks. It has been more than 15 years since we walked the coast-to-coast, and arguably the most famous US walk, the Appalachian Trail has no redeeming features. The Nakasendō came up and some accounts made it seem very appealing: hiking this ancient path by day, and staying in traditional inns at night. Sign me up.

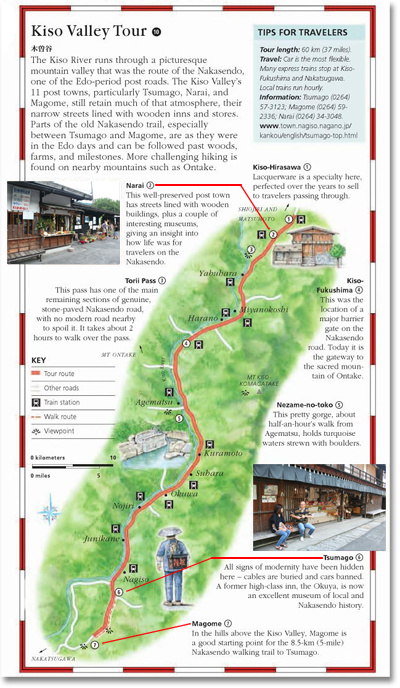

But as we started to do more serious research, the target became more ellusive. A couple of tour operators offered exactly what we were looking for, but the prices seemed crazy—$300-$500 per night. But as all-knowing as the interweb has become, there was spectacularly little information available for us to make the logistics work for ourselves. Adam tried getting help from Alistair and he too found himself grasping at straws. Finally, to my surprise, once again Eyewitness Japan came to the rescue. At this point we were only a couple of months from departure. But right there in the book was this whole-page spread on the Kiso valley, and the Kiso valley is famous for a) being pretty, b) being on the Nakasendō. Armed with actual place names, and now far enough into planning that I knew how to plan railway trips, I was able to cobble together a plan that could at least give us a taste, and that at least on paper, could be achieved using public transport.

But as we started to do more serious research, the target became more ellusive. A couple of tour operators offered exactly what we were looking for, but the prices seemed crazy—$300-$500 per night. But as all-knowing as the interweb has become, there was spectacularly little information available for us to make the logistics work for ourselves. Adam tried getting help from Alistair and he too found himself grasping at straws. Finally, to my surprise, once again Eyewitness Japan came to the rescue. At this point we were only a couple of months from departure. But right there in the book was this whole-page spread on the Kiso valley, and the Kiso valley is famous for a) being pretty, b) being on the Nakasendō. Armed with actual place names, and now far enough into planning that I knew how to plan railway trips, I was able to cobble together a plan that could at least give us a taste, and that at least on paper, could be achieved using public transport.

The two most interesting-looking sections of path seemed to be between Magome and Tsumago and Narai and Yabuhara. These two sections seemed well-preserved, away from the main road, reasonably long stretches (3+ hours). Better still, these were also far and away the three most historically significant towns, in that they were well-preserved, and indeed took pride in eliminating any signs of the 20th century in the hearts of the towns. At the very bottom of the map is Magome, then Tsumago, then Nagiso, the railway station. At the very top of the map is Narai, and a little to the south of that is Yabuhara. So a plan: take the train to Nagiso, walk back through Tsumago and follow the path to Magome, where we would need accommodation. In the morning, walk all the way back to the station at Nagiso and take the train north to Narai, where would spend the second night. In the morning, walk "over the mountain pass" (sounds fabulous) back south to Yabuhara, from where we could take the train all the way back to Nagoya and "civilization" again. So now we know we need accommodation in Magome and Narai. At least we have town names. Now the trick was to not just find accommodation, but of course we were looking for ryokans, these traditional inns. Another remarkably frustrating search, but finally I opened an ancient PDF file and found a list of ryokans in Narai. The best rated, now found, was also mentioned in a couple of other places. It was extremely well rated, but the warnings about it being small and difficult to get a reservation were unanimous. Here we were with only about a month to go now, but Adam called, and got the night we wanted. Holy moly. It was expensive. But we agreed that this was one place where we needed to splash out. We eventually secured a somewhat cheaper place in Magome. Done. The Nakasendō, and one of the highlights of the trip, was a lock.

That's the story of how hard it was to plan the trip, here follows the story of how easy it was to take it apart. And how much better it got as a result. First off, Alistair wanted to join us, at least for the first day, which meant he had to take the day off. Another day off. We had no choice on days, because now our night-stops were locked in. This also gave us an extra day with Alistair, which especially from Adam's perspective, was of course a huge plus. Alistair was happy to drive, so we had the luxury of no timetable, just a relaxing chauffer-driven ride with someone else taking care of navigation. We even caught a glance of the little castle at Gifu, which looked like a miniature Himeji. (My notes say Iwasaki but actually neither of these seem close to the route we should have taken, so something of a mystery.)

We drove straight to Magome, figuring we would find our lodging, then walk some of the trail with Alistair. Except we couldn't find the lodging. We didn't seem to be able to call it either, a piece of information I failed to fully comprehend until much later, because I knew I had a copy of the contact details in my trip notes, which I'd left in the car. Had I known this was the actual issue, I could so easily have fixed it. The good news is that as a result, Alistair instead made us a new reservation. In Tsumago. Brilliant! If we could find a way to get Alistair back to Magome, that means that we could now not only complete this section of the walk, but we would be able to have Alistair along for the ride! The bad news is that the following day the original reservation hit Adam's credit card with a 100% no-refund no-show fee. A severe dent in our beer kitty, but if that's the worst thing that happened on the trip, a small price to pay.

Okay, that's the pre-amble. Now down to business. This is what the interweb has to say ... The Nakasendō trail linked Kyoto to Tokyo during Japan’s feudal (Edo) period. It was the "road through the central mountains" (as opposed to four other routes, such as the Tokaido route which travelled the Pacific coast). These roads were travelled by feudal lords and their retinues, samurai, merchants, and travelers. Along the Nakasendō route were 69 post towns, where weary travelers could rest before continuing on the next leg. Naturally, Magome, Tsumago, and Narai were three of them. By the way, the first three characters on the stone here (中山道) mean Nakasendō

and even I need to learn that, since this is often the only indicator of the route.

Okay, that's the pre-amble. Now down to business. This is what the interweb has to say ... The Nakasendō trail linked Kyoto to Tokyo during Japan’s feudal (Edo) period. It was the "road through the central mountains" (as opposed to four other routes, such as the Tokaido route which travelled the Pacific coast). These roads were travelled by feudal lords and their retinues, samurai, merchants, and travelers. Along the Nakasendō route were 69 post towns, where weary travelers could rest before continuing on the next leg. Naturally, Magome, Tsumago, and Narai were three of them. By the way, the first three characters on the stone here (中山道) mean Nakasendō

and even I need to learn that, since this is often the only indicator of the route.

Although there has been much modern development along the Nakasendō, a few stretches remain in its original form, while others have been restored in more recent decades. The most well-known section lies in the Kiso Valley, between Tsumago-juku in Nagano Prefecture and Magome-juku in Gifu Prefecture. This eight-kilometer section of the Nakasendō can still be travelled along comfortably by foot, and both Tsumago-juku and Magome-juku have preserved and restored the traditional architecture. The walk between the historical post towns requires two to three hours to walk, with forests, restored paving and fine views of waterfalls along the way. See? I told you.

Magome was not exactly what I had in mind by restored and historical, but it was quant enough, and definitely touristy, with its steep narrow main drag clearly paved as a sidewalk rather than a road. As one of my brochures claimed about another site "it is not particularly remarkable, but still quite pleasant." Ironically, there were a significant number of foreign tourists about, and even more ironically, give the trouble we had gone to to wrinkle this place out, several fairly large groups were clearly walking the Nakasendō. I know this because I asked them. Americans and Brits. And yes, they were on guided tours so perhaps paying those megabucks prices. I'm not sure why this gave me such a smug sense of independence, but it can't be denied even as I acknowledge the vital role Alistair was playing in keeping our "independence" afloat. I'll put it down to resistance to their rather smug tone. Anybody would think they were on the home straight of the Appalachian Trail.

That's Magome's main drag below, with Alistair and Adam in the background, doubtless looking for lunch. Which of course they found, and the other snap below is the view out of the back of the cafe. Life is good. We think the peak in the clouds must be Ontake, an apparently famous local hiking attraction.

I don't remember what the boys ate, but I had oyaki, a local delicacy. "Honorable cooked thing" Alistair assured me was what these were. Since I ordered all three flavors, what looked like three small loaves were served up, to the obvious consternation of the waitress. Alistair muttered something to her along the lines of "foreign lunatic" and shrugged his shoulders. Much relieved that I seemed to be in good hands, she beat a hasty retreat. Obviously I had to finish them all, and just as obviously it was way more fun for the boys to refuse to help than it would have been to share them, so we sat for a while admiring the spectacular view as I slowly turned myself into the honorable stuffed thing.

|

Finally I washed down the last piece of oyaki with my last mouthful of beer (doubtless also a blasphamous way to consume honorable cooked things) and we were ready for the off. Magome to Tsumago is 5 miles (8 km). "The 3-hour walk can be most enjoyable during the seasons of fresh verdure and autumnal tints." Oh well, we missed both of those. At least it wasn't January and February's half meter of snow.

I didn't capture the bear warning, but around this time we were also seeing these warning about excavating through not just any old cable, but telephone cable specifically. |

|

Despite the lack of autumnal tints, it was a pleasure to just wander along, lagging a little behind the boys, watching them chatting, which they seemed to be able to do for hours on end. It was also noticably cooler up here in the mountains. It was still hot, but by comparison it was quite pleasant.

Some of the stands of trees were bamboo, thirty or forty feet high, and with trunks 4-6 inches in diameter. For reasons none of us really seemed to understand, Adam started to flex one of them to test its tensile strength. It snapped like a pencil about five feet above the ground, leaving a huge ugly gash of a stump, and the top thirty feet, still attached, now lying across the road. Like naughty schoolboys in unison and in silence we all grabbed the "pole" and managed to stuff it behind the guard rail at the side of the road. Then we hurried on.

|

We took a short detour to visit the Odakimedaki Waterfalls. The sign made it clear that they are a pair, male (on the left) and female (on the right). I'll go out on a limb and suggest that the name means male (Odaki) female (Medaki) . If you can figure out why, even if your explanation is wildly inappropriate, I still want to hear it. I got nothin'. I thought we knew more about them than that, but all I can find now is a note in a brochure to the effect that the waterfalls famously feature in the romance between the great swordsman Musashi (1584-ish to 1645) and his sweetheart Otsū in Eiji Yoshikawa's (apparently) famous book "Miyamoto Musashi." Anyway, a pleasant enough spot, and I'm quite pleased how well the results came out, considering how little light there was in this shady glen. |

|

Below Left: Kanji lessons for RT. Three different Nakasendō signs of clearly different vintages, though as here, most of the time the path was not exactly difficult to find or follow.

Eventually we came to this little hamlet. I say hamlet: there were two buildings, an outhouse on the right (perfectly timed and placed) and this building on the left. The proprietor, who can be seen in the gloom of the second picture, was standing in the road. He was about 900 years old, and was trying to persuade another couple we had just caught up with to step inside. The scene reminded me eerily of The Witch trying to persuade Snow White to take the poisoned apple. The couple scurried on. Our turn. What did we have to lose? Seriously this was some highway robbery scam with its own building? Alistair said "he wants us to take tea."

Eventually we came to this little hamlet. I say hamlet: there were two buildings, an outhouse on the right (perfectly timed and placed) and this building on the left. The proprietor, who can be seen in the gloom of the second picture, was standing in the road. He was about 900 years old, and was trying to persuade another couple we had just caught up with to step inside. The scene reminded me eerily of The Witch trying to persuade Snow White to take the poisoned apple. The couple scurried on. Our turn. What did we have to lose? Seriously this was some highway robbery scam with its own building? Alistair said "he wants us to take tea."

To me, it was just a priceless cultural experience. It was something straight out of the museums we'd visited over the weekend. Except that the fire was burning in the grate. It gave the room a warm, toasted, smell, and cast a little light into the overall gloom. It was easy to imagine how cosy it would be when snow drifted up against the door-assuming all these open doors and screens could be closed up effectively. We were served our little cups of tea, along with a small cookie. It was certainly not matcha, but it was nice, not too strong, and naturally sweet. I could happily have downed half a dozen more of the typical itty-bitty cups, but this was clearly unacceptable.

We sat savoring the scene for several moments, then it was time to push on. The old man didn't even want any money from us. It was just a service he provided to passing travelers. We were somewhat conscious of the time: we were not exactly rushed, but at the same time we were also not exactly sure where we were, and until we had found the bus station, and confirmed the rumors about the bus and its schedule, it was hard to relax.

We sat savoring the scene for several moments, then it was time to push on. The old man didn't even want any money from us. It was just a service he provided to passing travelers. We were somewhat conscious of the time: we were not exactly rushed, but at the same time we were also not exactly sure where we were, and until we had found the bus station, and confirmed the rumors about the bus and its schedule, it was hard to relax.

So on we marched. This next picture tries to capture one of the last farms we passed by before entering Tsumago. Somehow the scene was the essence of rural Japan for me. As I mentioned before, rice grew in every available space. Here it is growing in strips of what, a quarter acre each? In the middle is a tree in flower, despite it being the last week in September. It's pale violet flowers reminded me of Jakarunda. Finally there is the cemetery, and the beautifully manicured trees surrounding it, and all set against the darker green of the forest we'd popped out of, and would shortly pop back into. The whole scene is very pale which somehow makes it even more difficult for the image to do the scene justice.

And with that, before we knew it, we were in Tsumago. Which looked just like the brochures, and therefore just like I'd imagined it. Somehow the contrast between old and new is starker than, say, the US or the UK. Especially the UK. There are plenty of buildings in the UK that are 15th, 16th, or 17th century, and they look older than modern buildings, but most modern buildings are not exactly cutting edge—they reflect their heritage. I think part of the issue is that these Japanese buildings look so flimsy, but that's because they are. They are designed to be rebuilt, and rebuilt often. It was true of the temples too. The vast majority had been rebuild multiple times over the centuries. In a world of earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons, this makes a lot of sense, and also makes sense of Alistair's observation that the half-life of a house was 25 yrs. All the value in a 25 yr old home was the land, which you then rebuilt on. He was hunting for a 25 yr old property with a house that he could tolerate NOT rebuilding. Meanwhile, the new buildings in Japan, either because they only need to last for 25 years, or more hopefully because technology can now help hugely in standing up to the forces of nature, tended to be extremely modern-looking, which is an approach that is somewhat harder to pull off in London or Boston, although it would seem that some are now trying (The Shard?).

And with that, before we knew it, we were in Tsumago. Which looked just like the brochures, and therefore just like I'd imagined it. Somehow the contrast between old and new is starker than, say, the US or the UK. Especially the UK. There are plenty of buildings in the UK that are 15th, 16th, or 17th century, and they look older than modern buildings, but most modern buildings are not exactly cutting edge—they reflect their heritage. I think part of the issue is that these Japanese buildings look so flimsy, but that's because they are. They are designed to be rebuilt, and rebuilt often. It was true of the temples too. The vast majority had been rebuild multiple times over the centuries. In a world of earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons, this makes a lot of sense, and also makes sense of Alistair's observation that the half-life of a house was 25 yrs. All the value in a 25 yr old home was the land, which you then rebuilt on. He was hunting for a 25 yr old property with a house that he could tolerate NOT rebuilding. Meanwhile, the new buildings in Japan, either because they only need to last for 25 years, or more hopefully because technology can now help hugely in standing up to the forces of nature, tended to be extremely modern-looking, which is an approach that is somewhat harder to pull off in London or Boston, although it would seem that some are now trying (The Shard?).

That said, after restoring 20 of the houses to their Meiji (1858-1912) glory, in 1971 a charter was agreed to preserve the town and that no place in Tsumago should be "sold, hired-out, or destroyed." Good luck with that. In 1976 the preservation effort was intensified to include (no) TV aerials, telephone poles or electricity cables to be visible. We did a quick lap of the main drag, looking for a bar to return to once we'd located the bus station. We had about 45 minutes to spare. Perfect! We had enough time to also locate our inn, for Alistair to confirm that our reservation was all set, and that we'd be fine after this despite our lack of language skills. Then back to the bar, where the boys had a beer, and I had sake, both served with pickles. Adam: "Naturally."

Finally it was time to see Alistair onto the bus, punctual of course, and then after a brief stop in a store where I bought a single serving of sake sold in it's own glass (just in case) we made our way back to the inn. Tonight we were in a minshuko, a family-run inn. Not as expensive as the ryokan booked for the following night, but fairly special by our standards, and at least was "traditional." So was the ryokan of course, about which we knew nothing, hence some of our reluctance to spend too heavily when we didn't even know what we were paying for, so this would make an interesting comparison.

The minshuko was down a little side alley, and although not 50 ft off the main drag, it was a bit of a shock to find that once we were inside, it was surprisingly modern, and western-feeling. It was of course very cramped by American standards, but I've been in many very comfortable English homes that were no bigger. The proprietor had warned Alistaire that they only had a "four-and-a-half-tatami-mat room" and this was the first real sign that we were not in Kansas anymore, because the four-and-a-half tatami mats were the only things in the room.

The minshuko was down a little side alley, and although not 50 ft off the main drag, it was a bit of a shock to find that once we were inside, it was surprisingly modern, and western-feeling. It was of course very cramped by American standards, but I've been in many very comfortable English homes that were no bigger. The proprietor had warned Alistaire that they only had a "four-and-a-half-tatami-mat room" and this was the first real sign that we were not in Kansas anymore, because the four-and-a-half tatami mats were the only things in the room.

The proprietor brought in two stacks of bedding, which he put at one end of the room, along with towels, and of course our yukatas. We had about an hour until dinner time, so we quickly changed into our yukata and made our way to the bathroom. Again nothing to write home about, modern, a one-holer where we surprised a fellow guest who was so apologetic we assumed until we saw him later at dinner that he was a member of the household stealing some quality time. Man it feels good to scrub off the sweat of the day and then float in the almost-but-not-quite-too-hot-to-sit-in water. Suitable cleaned up and probably glowing a little from the soak, we then went back to our room and hung out reading a little (and drinking the emergency sake) until the call to dinner. I remember distinctly realizing that this was the first time we were home in time to want to do anything other than crash. It was very relaxing.

There were four tables at dinner. On my left was a Dutch couple. Quietest Dutch people I ever met. They didn't seem to want to talk to each other much, never mind us. The few things that passed back and forth between them were whispers. To my right was our friend from the bath, and his companion. They were university types, spending a couple of days up-country. They were much more forthcoming, but of course mostly wanted to know about us, where we were from, what the heck we were doing here. At the far end of the line were three middle aged women who were having a ball, laughing, joking, drinking sake.

The proprietor brought out huge trays, each crammed full with little dishes, and placed one in front of each guest. The Dutch couple were vegetarians, so for some reason they seemed to have the same tray, but with a different type of fish. There were pickles of course, and tempora, (top right) and we were also able to identify the edamame at the stern end of the green boat at the top of the bottom left quadrant. What was really getting my attention was in the bow of the boat. Our friend at the next table did not know either, but he asked the ladies who thoroughly impressed me by not only knowing the Japanese (inago) but also the English: crickets. I think Adam was being polite because he didn't eat some of his pickles and instead offered them to me (yum) but otherwise we polished off everything, washed down with a small bottle of shochu (nod of approval from the professor). Both the fish and the crickets were highlights because of their strong teryaki flavor which I love, but the fish was also sort of smoky, and so well cooked that it was easy to pick chunks off with one's chop sticks, leaving a clean spine connecting the head and tail when one was done.

The proprietor brought out huge trays, each crammed full with little dishes, and placed one in front of each guest. The Dutch couple were vegetarians, so for some reason they seemed to have the same tray, but with a different type of fish. There were pickles of course, and tempora, (top right) and we were also able to identify the edamame at the stern end of the green boat at the top of the bottom left quadrant. What was really getting my attention was in the bow of the boat. Our friend at the next table did not know either, but he asked the ladies who thoroughly impressed me by not only knowing the Japanese (inago) but also the English: crickets. I think Adam was being polite because he didn't eat some of his pickles and instead offered them to me (yum) but otherwise we polished off everything, washed down with a small bottle of shochu (nod of approval from the professor). Both the fish and the crickets were highlights because of their strong teryaki flavor which I love, but the fish was also sort of smoky, and so well cooked that it was easy to pick chunks off with one's chop sticks, leaving a clean spine connecting the head and tail when one was done.

We hatched up another cunning plan for the following day. Now we were only about an hour's walk from the station at Nagiso. The original plan called for us to travel to Narai, then walk back across the mountain pass the following morning. Now we had gained this extra time, what if we took the train to Yabuhara and walked north to Narai? If we had time to do that, it would mean that the following morning we would be ready to travel back to Nagoya right after breakfast. Potentially we could be back there as early as lunch time, gaining half a day. Adam: "Kobe!" RT: "Done!"

Despite the early night we were out like lights, and the next thing I was aware of was the breakfast gong and time to eat again. Multiple tragedies.

We headed out of the village looking for Nakasendo signs, and this time they also included the arabic letters JR: Japan Rail, confirming the route. Along the way, multiple photo ops. One we looked for for some time was called Carp Rock, which was mentioned on several maps, and apparently was striking enough to be mentioned in a novel. There were sketches of it even, showing that indeed it looked most carp-like. So why was it so hard (impossible) to find? Later while re-reading some of our literature I finally discovered a reference to the fact that the rock was "damaged" by an earthquake. In 1891.

I love the color of ripe rice. It looks so promising, so full of life and stored up energy, like a loaf of bread fresh out of the oven, or the cream on top of a bottle of milk. This ready to harvest field on the northern outskirts of Tsumago was close enough to the path for me to finally get in for a close up. Looks just like grass, by strange coincidence. I'd still like to see the terraces of the far east, the farmers in coolie hats bent over in their fields. but that is probably the spring season. The harvest will now always remind me of Japan. |

|

|

There were countless fish ponds. It was more common for village houses to have one (or two) than not, though most were just galvanised tanks. Occasionally the setting was more elaborate, like this one, and their occupants tended to be prettier too. One guesses that additionally their life-expectancy was also significantly longer. But again this was just a random view at a random house—I even had to step off the path a little in order to take the picture.

There were countless fish ponds. It was more common for village houses to have one (or two) than not, though most were just galvanised tanks. Occasionally the setting was more elaborate, like this one, and their occupants tended to be prettier too. One guesses that additionally their life-expectancy was also significantly longer. But again this was just a random view at a random house—I even had to step off the path a little in order to take the picture.

Jizō is a Bodhisattva, one who achieves enlightenment but postpones Buddhahood until all can be saved. One of the most beloved of all Japanese divinities, Jizō is popularly venerated as the guardian of unborn, aborted, miscarried, and stillborn babies (Mizuko Jizō). Local women usually take care of the Jizō statues and provide them with the hand-knitted hats and hand-sewn bibs. It has been suggested that by doing so, the women are accruing merit for the afterlife, a common theme in Buddhism. Jizō loves company, and the many sites we came across generally had half a dozen or more patiently standing in line like this.

Soon we were following the rail line into the center of Nagiso. We checked the train schedule and we had about an hour before the next local train which would take us to Yabuhara. So we grabbed a hot coffee from the vending machine across the street and then headed down the road to see if we could find the Momosukebashi Bridge which we'd noticed on a couple of posters, and finally glimpsed from the path as we approached Nagiso.

To our pleasant surprise, the bridge was a) constructed out of wood, b) pedestrian only. Narrow guage rail tracks ran down the center, implying an interesting history—they were clearly no longer in use. Discovering it was for foot traffic only increased the desire to walk all the way across it. Next to the bridge was a map that implied that it ought to be possible to walk across, and return via another bridge, getting us back to the station in plenty of time for the train. So off we went. Right in the middle we were stopped by a old couple coming the other way, who wanted to practice their English on us, so we spent a couple of minutes satisfying their curiosity.

To our pleasant surprise, the bridge was a) constructed out of wood, b) pedestrian only. Narrow guage rail tracks ran down the center, implying an interesting history—they were clearly no longer in use. Discovering it was for foot traffic only increased the desire to walk all the way across it. Next to the bridge was a map that implied that it ought to be possible to walk across, and return via another bridge, getting us back to the station in plenty of time for the train. So off we went. Right in the middle we were stopped by a old couple coming the other way, who wanted to practice their English on us, so we spent a couple of minutes satisfying their curiosity.

The other side was a sort of park. It looked like a rough golf course, with stretches of open and fairly short grassy areas threading in between clumps of big pines and all confined by the boulder-strewn river with its turquoise water swirling by. It turns out it was a sort of golf course. Trust the Japanese to come up with a varient called "putter golf" where there are no real fairways, you just chip from the tee onto the green and then putt. You only need two clubs. This one was fairly basic, so it looked more Scottish than American (Scottish greens in my limited experience looking like American fairways, and American greens looking like English snooker tables).

The local train meandered up the narrow tree-covered Kiso valley for over an hour, criss-crossing the fast-flowing river and stopping every five or ten minutes at the next little town. It was little wonder that the area was such a tourist trap with brochures advertizing scores of temples, hot springs, walking trails (for "forest therapy"), even horse farms, and skiing.

The local train meandered up the narrow tree-covered Kiso valley for over an hour, criss-crossing the fast-flowing river and stopping every five or ten minutes at the next little town. It was little wonder that the area was such a tourist trap with brochures advertizing scores of temples, hot springs, walking trails (for "forest therapy"), even horse farms, and skiing.

As soon as we got off the train we needed to find lunch. Firstly because it have been well over 90 minutes since we last grazed on something, but more importantly because presumably once we started walking, there would be no opportunity until we reach Narai. We'd walked the length of Yabuhara and even passed the sign indicating where the Nakasendo set off up the hill and found nothing open. Finally Adam stops outside this building and says "Phew. A restaurant."

RT: "Seriously? Where?"

Adam: "Right here."

RT: "I see right here. But I see nothing indicating a restaurant. What are you looking at?"

Adam: "That purple awning says it is a restaurant, and the flag on a stick says it is open."

RT: "Sheesh. I'd starved to death before figuring that out. How's a mere mortal supposed to know that?"

And so began one of my favorite experiences of the whole trip. All the more so because of its serendipitous

discovery.

And so began one of my favorite experiences of the whole trip. All the more so because of its serendipitous

discovery.

Once again we entered a historical scene, all the more surprising this time because it was not an old man's barn, it was a commercial operation, a restaurant that presumably had to live up to 21st century health and safety regulations. The fire was set into the middle of a large Japanese-low table. After removing our shoes, we stepped up onto the platform floor, and then stepped down again against the table. The seat was the edge of the platform. The trough under the floor was decidely cool, so much so that it was something of a relief for my toes to find that there was a heating pad down there.

There was one other customer already there, and he spoke better English than pretty much anyone else we met. Wouldn't you know it: he and Adam were in very related professions. They practically had common connections. He was a regular customer, and when we went to take a picture, a) he insisted on taking it, and b) he got his friend the chef to come out too. I love this picture, capturing the atmosphere as well as the moment.

The house speciality was zarusoba (soba noodles), so I had the classic. The nutty flavor of the cold noodles, contrasted the hot (temperature and spicy) miso make a delightful contrast in the mouth.

|

When we were done, the chef brought out these tiny perilla (plum, according to our fellow guest) sorbets as a complimentary dessert. They were perfect of course. I could have sat here all afternoon, or at least long enough to eat it all again, but we had a mountain to climb, so we paid our dues, said our good-byes, bowed our exit and headed back out into the heat. It did not take us long to get back to the path, and immediately it started to climb out of the village. As with walks everywhere, in my vast experience, the number of folks still on the trail tapers off exponentially, and within an hour we were pretty much on our own. |

|

So apart from the little Buddhist shrines that cropped up on a regular basis, this was much more of a solitary, steady uphill push, with no reason to stop except to catch our breath and try to drink enough to keep ahead of the sweat. The Torii Pass, for which this section of the Nakasendo is famous, was considered one of the most difficult ones to get through on the whole highway. It is a 2000ft (600m) climb up and then down in less than 4 miles (6 km to be exact), which is fairly respectable I suppose, especially in your Shogun finery. The towns either side (and especially Narai) prospered because travelers rested and stayed there in order to prepare for crossing the pass.

So apart from the little Buddhist shrines that cropped up on a regular basis, this was much more of a solitary, steady uphill push, with no reason to stop except to catch our breath and try to drink enough to keep ahead of the sweat. The Torii Pass, for which this section of the Nakasendo is famous, was considered one of the most difficult ones to get through on the whole highway. It is a 2000ft (600m) climb up and then down in less than 4 miles (6 km to be exact), which is fairly respectable I suppose, especially in your Shogun finery. The towns either side (and especially Narai) prospered because travelers rested and stayed there in order to prepare for crossing the pass.

Near the top we took a "short" detour to check out the Ontake Shrine. We were somewhat taken aback by how far and steep it was, and were pleased to find a second exit that brought us out closer to the top and saving us from losing all the height again (only to have to regain it once more of course). The shrine had a commanding view down the valley, and reminded us both much more of an excellent military base than a religious one. It also had a neglected air that reminded me a lot of some of the places we visited in Ghana. Not so much that they had been great once, something a little more desperate than that: something that someone had tried hard to make great, but had then abandoned.

Once back on the main path, we were immediately confronted with multiple choices, which is a serious problem on top of a mountain—you do not want to end up in the wrong valley. Luckily, we had just passed the only other folks we'd seen on the mountain, two old men laying out a picnic. It was surprising difficult to get them to understand what we were asking. They didn't even seem to understand the words Nakasendo or Naraii. Eventually they agreed on a direction to point, and we were relieved to have their choice confirmed just a few minutes later when we crested at what was clearly the Torii in Maruyama Park, and the namesake of this section of the Nakasendo.

Again, not exactly a well-visited spot, and the air of neglect was amplified by the yellow Do Not Cross tape which I'm pressed up against to avoid it getting in the picture. We'd seen plenty of torii that were clearly concrete, which doesn't seem quite right to me, but this is the only one not painted vermillion. Still, vermillion or not, a torii is a torii, and the confirmation of location was worth it if nothing else.

As you can see from this picture looking down on our target Narai, taken as soon as we got a clear view through the trees after crossing through the Torii pass (1197 m or 3927 ft), this is not exactly the Himalayas, so the pass was a fairly low key experience. It certainly didn't feel like a White Mountain 4000 footer. I guess it could be a very different story in the winter, but on this hot autumn afternoon it was benign enough.

As you can see from this picture looking down on our target Narai, taken as soon as we got a clear view through the trees after crossing through the Torii pass (1197 m or 3927 ft), this is not exactly the Himalayas, so the pass was a fairly low key experience. It certainly didn't feel like a White Mountain 4000 footer. I guess it could be a very different story in the winter, but on this hot autumn afternoon it was benign enough.

Reading back through this, I realise I make it seem like a bit of a slog, which I suppose it was, but don't think for a second that we did not thoroughly enjoy it. We did. It was pretty, it was peaceful, it was (mostly) effortless to navigate, and it was just the contrast to some of the days before and others to come that we were hoping for.

Like rides in the car, walking is one of my favorite forms of family quality time. There is no pressure to make conversation just to ensure the other person doesn't wander away. Instead there is the silent pleasure of simply sharing a common experience, and so we just marched along letting the scenery drift by, each absorbed by his own thoughts.

Breaks in the trees gave us regular hints that we were on the right track as we descended towards the roofs of the houses, and a couple of times folks passed us in the opposite direction, everyone seeming a little surprised to meet anyone else, so there was a polite tip of the hat as they went by.

Here a bridge crosses a deep ravine, and the path twists and turns sharply to reappear on the right of the photo as it headed on down following the left bank of the ravine.

Here a bridge crosses a deep ravine, and the path twists and turns sharply to reappear on the right of the photo as it headed on down following the left bank of the ravine.

A final flurry of shrines and markers, and then we done.

A large welcome sign at the edge of the village proclaimed, in English: "Narai-juku was one of the post towns on the Nakasendo highway officially ruled by the Edo Shogunate and situated exactly between Edo and Kyoto. As it retains a historical row of Edo period houses along the street, it was confirmed as a Cultural Asset in 1978 and is maintained by the government grant system. [ ... ] The buildings are unique in that the second floor overhangs the first, with eaves sloping further to overhang the entire building. Most of the roofs now have steel sheets, but originally they were wooden slats held down by rocks."

Well, I say done. We were in Narai all right, but we agreed that we had two orders of business before we could look for a bar: find the ryokan, and confirm that we knew where the station was, and what time the trains left in the morning. And of course the station was as close to the northern edge of the village as we were now to the south.

As advertized, the town was awash in buildings with the second floor jutting out over the ground floor, and the roof overhanging both by a considerable margin. If the streets had not been so wide, it could have been quite claustrophobic, like The Shambles in York.

As advertized, the town was awash in buildings with the second floor jutting out over the ground floor, and the roof overhanging both by a considerable margin. If the streets had not been so wide, it could have been quite claustrophobic, like The Shambles in York.

We must have passed by the ryokan but never noticed it, but only being mid-afternoon we were in no particular hurry, so we wandered in and out of some of the shops. I was vaguely looking for some laquer-ware, for which this region is famous. The better the quality, the more it seemed to resemble a plastic imitation, both in look and feel. And the expensive stuff was very expensive. My enthusiasm wained.

Eventually we ended up at the station, where I was heartened to find that the schedule confirmed to the minute what I'd noted down from my interweb research. With all our ducks lined up we wandered back up the street, stopping often to take pictures in the perfect afternoon light, and looking more carefully at the signs since it was now clear that nothing would be in English.

Eventually we found it, about two-thirds of the way back. I suppose eventually I would learn how to read the clues, but once again I was amazed at how difficult it was to identify a commercial establishment from a residential one.

Echigoya-Ryokan was expected to be a highlight, and it did not disappoint. As we stepped inside, the inn-keeper appeared, as if he had just been waiting for us. He welcomed us warmly, even though we couldn't understand what he was saying. It was obvious that we needed to remove our shoes and leave them here in the foyer. He carried our back packs as he led us passed the little garden (a requirement in the ryokan "definition") and into the back of the building. When he got to our room, just like they do in the movies, he knelt down on the floor before sliding the paper door open, then shuffled through on his knees, dragging our packs with him. We were not sure if we were supposed to do the same, but inside he got to his feet again, so we sort of shuffled quickly through the door and hoped he wouldn't be too offended. I think we bowed too for good measure, good will, and to make ourselves as low as possible. I figure we'd have looked even bigger chumps if we'd been on our knees but we were supposed to be on our feet.

The washbasin was a cedar tray, four feet wide, two feet across, and about a three inch lip all around, and the whole tray set at about a thirty degree angle so the water ran to the front, and then down to one side and out. This was in the corridor. In a room by itself was the bath (with an anti-room for changing). The bath was about a four foot by three foot by three foot box filled to not-quite-the-brim with water, and with slats across the top covering it until you were ready to use it.

The washbasin was a cedar tray, four feet wide, two feet across, and about a three inch lip all around, and the whole tray set at about a thirty degree angle so the water ran to the front, and then down to one side and out. This was in the corridor. In a room by itself was the bath (with an anti-room for changing). The bath was about a four foot by three foot by three foot box filled to not-quite-the-brim with water, and with slats across the top covering it until you were ready to use it.

Done with our tour, we returned to our room and the inn-keep served us tea. Again, of course not the full tea ceremony, but this time there definately was more ceremony. After whisking the matcha in its pot and steeping it by cupping the pot in his hands, he served it out into our two little cups by going back and forth between them. After half a dozen passes, and the stream had turned to drips, I noticed that the drips were the same: five into one cup, five into the other. Three into one, three into the other. Then two, and finally, slowly, the last single drip into each. The resulting tea is almost thick enough to stand a spoon in, like a good French hot chocolate. He prompted us carefully by placing the cups in the palm of our left hands, and we dutifully turned the cup clockwise about 90 degrees with our right. We were then supposed to drink it in three gulps, but I confess to taking a couple more than that, I was so keen to savor the flavor and the moment.

The innkeep then showed us our yukatas, though these were far more than that. Let's call them robes, because they were not kimonos either. He said he would return later with our meal, and in the meantime of course we could bathe. Again there seemed no choice about what to eat, but we could choose our beverages. Obviously this meal called for something traditional so it had to be sake or shochu. We chose shochu.

Not choosing from a menu, having food brought to you until you have had enough, is hands down my favorite way to be served. This can come about for a number of reasons: some restaurants (like this one) are just one setting; I've also been places where they know the folks at the table well enough that they just bring out dishes until we call a halt; and of course the most frequent way is when someone at the table just takes control. Part of what makes these occasions special is knowing that someone had the courage to make a decision on everyone else's behalf, some of it is in taking the responsibiity to play ones part, and to be prepared to eat whenever is set down in front of you whether you like it or not. But mostly it is the simple pleasure of not having to do any thinking, and best of all, every arriving dish is a surprise.

So while we enjoy the anticipation of our surprise dinner, time to bathe. After a good shower, the hot tube is as usual at the exact temperature that does not make you think you are going to burn yourself, but as you sink in you wonder for a second if you might pass out. The vertical sides to the tube are not condusive to a long soak, but everything else is, especially the clean, sharp smell of the cedar. So five minutes or so is a compromise, plus I confess I'm looking forward to trying on my robes. Then back to enjoy the room. I tried to read, but I couldn't focus, trying to take in every detail of the dream I felt I was in, so I could remember it when I woke up.

|

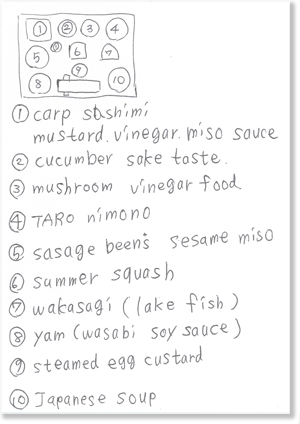

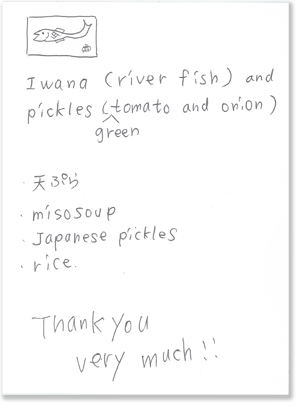

Due to a minor miscommunication, tragically we ordered sake and shochu rather than sake or shochu. Oh well, them's the breaks. I asked the innkeep if he would write down what we were eating. Even if it was in Japanese, at least I could have it translated later. He said he would ask his wife, and asked if was okay to get it in the morning. These scans are the little masterpieces she came up with. Best of show was the carp sashimi (1) was served over flaked ice, which is causing the blurred appearance. Once again I was in heaven with all the different pickles. Perhaps not surprisingly the carp was only surpassed by the iwana that followed. |

|

|

|

|

Well refreshed from the sake-shochu combo, I helped Adam finish his pickles and then after a perfectly timed interval, the innkeeper returned and took away all the dishes. When he came back, he was carrying bedding, and quickly turned the dining room into a bedroom. Again, I tried to read, and got a little further this time but conditions were ripe for sleep, and we both soon succumbed.

|

We never did figure out how things were timed so precisely, but a few minutes after we awoke, the process was reversed, the bedding disappeared and the room was converted back to a dining area for breakfast. We were touched and I have to say a little honored, given the Japanese emphasis on decorum, position, and protocol, when the inn keeper felt comfortable enough tp ask if it would be okay to bring his daughter to meet us, as she was dying to see these strange creatures. Of course she was very shy, but nevertheless could not resist staring at us and after a little coaching, and a lot of smiling, proudly produced the three or four words of English that she so wanted to try on us. I'm not complaining, it's a lot more than the 1 or 2 words that I knew of her language. |  |

The receipt for our stay was a work of art, complete with a postage stamp which I assume indicates some sort of tax paid. All settled up it was time to get to the train, but not before the whole family came out to say good bye. The kids were even allowed to interupt their teeth-cleaning. That's our little morning visitor on the right, still clutching her toothbrush.

The receipt for our stay was a work of art, complete with a postage stamp which I assume indicates some sort of tax paid. All settled up it was time to get to the train, but not before the whole family came out to say good bye. The kids were even allowed to interupt their teeth-cleaning. That's our little morning visitor on the right, still clutching her toothbrush.

We had about twenty minutes to stroll back through the town one last time, grab hot coffees from the vending machine outside the station, and at 8:26am as the slow train pulled out of the station, our Nakasendo adventure was officially over.

We changed trains in Kisofukushima, and after an event-free 150 minutes, we were back in Nagoya in time for lunch. Or, more accurately, in time for Kobe. We booked two seats on the Shinkansen, bought a couple of bento boxes, and by noon were on our way to our next (short!) adventure.

The path climbed at a steady pace out of the village criss-crossing the road at regular intervals. As soon as we got more than 50ft or so away from the road, there would be a bell hanging by the path, and more signs about the dangers of bears. Everybody we saw dutifully clanged the bell, and so we did too. Japanese warning signs, which were everywhere, always did a great job overcoming the language barrier.

The path climbed at a steady pace out of the village criss-crossing the road at regular intervals. As soon as we got more than 50ft or so away from the road, there would be a bell hanging by the path, and more signs about the dangers of bears. Everybody we saw dutifully clanged the bell, and so we did too. Japanese warning signs, which were everywhere, always did a great job overcoming the language barrier.