Nagoya

Nagoya as a destination was not high on my agenda, but as the Shinkansen stop closest to Adam's friends Alistair and Maiko-chan, it rapidly gained promenance. An opportunity to spend the weekend as the guests of a Japanese family was a huge draw for me, and of course the opportunity to hang out with his old friends was a huge draw for Adam. It was touching to see how much they enjoyed each other's company, and we had an absolutely fabulous time with them. They were first-rate hosts, and had planned the whole weekend out in great detail. The only think I remember about Nagoya was eating and drinking. Partly because it was some, not to say most, of the best eating and drinking we did the whole trip, but partly because I really don't think we did anything else in town. The rest of the weekend we spent all sorts of other places. But for now let's get back to Nagoya.

We started out on Friday afternoon when Alistair meet us off the train late in the afternoon. Unheard of, he'd had to take time off work to do so, and it seemed like the whole factory knew about this scandalous behavior. We dropped our bags off at the car, when we finally found it. Part of the careful choreography, Maiko-chan had driven in that morning, and Alistair had taken the train from work into town. This way we had the car so we could be driven home, but Alistair had not parked it himself.

Alistair wanted to have a couple of beers at the Bristish pub, which was fair-enufski, but I quickly switched to shōchū. It's hard to describe, but you can recognise a "British Pub" the world over. They all have the same sort of feel, and they all, as Douglas Adams might have observed "taste/look/feel/smell almost, but not quite entirely, unlike a British Pub. For a start, the real thing would never dream of calling itself British. English, Scottish, sure. Welsh maybe. Perhaps even the occasional (Northern) Irish. But never British. Then there's the booze. A good pub has at least a couple of cask-conditioned beers, which need pull-handles to draw the beer up without putting it under pressure. And all the liquor is hanging upside down in a row at the back of the bar with optics on the bottom, allowing a very precise measure of liquor to drop into the glass pressed up under it. Without these it just isn't right. The last major thing that springs to mind is that "real" pubs always include a large measure of homely, local, unique, old bits and pieces that are part of the long life and history of the pub and the people it has served. Not things hidden behind glass and locked in cabinets, but odds and ends sitting on tables and mantlepieces, leaning against walls. British Pubs are not bad, they just don't remind me of "home." Anyway who cares about me? Adam and Alistair enjoyed several pints, and I enjoyed listening to their sparring while I mentally critiqued the decor, and soon enough it was time to meet Maiko-chan and on to the evening's real entertainment: Saami Restaurant.

We were shown to our spot, along the short end of the L-shaped bar, behind which the sushi chefs worked their magic. Maiko-chan took immediate control (hurrah!) to the point that the waiter only brought one menu and handed it to her. Let the performance begin. You can't taste how incredible everything was, but at least you can see what a visual feast it was from these few snaps I took of my favorites.

Maguru. This is tuna. There are three grades on the plate, as you can clearly see from the different colors. On the left is toro, the fattiest, from the belly. It was still tuna, but it was so rich in texture and flavor it reminded me of fois gras. In the middle was chutoro, the medium fat, and on the right that familiar meaty red of akami, "regular" tuna. For everyday use, I definitely prefer the leaner flavor of the "regular" tuna, but I'll never forget the regal flavor of the belly cut. One was clearly eating something very special.

Probably the highlight presentation-wise, the ishidai or striped beakfish was swimming around in the aquarium when we arrived, and I didn't noticed him being scooped out, but he was definitely gone later. I was very relieved that he wasn't still moving when the plate was presented, but wow, what a presentation. Note the rose at top right. Ishidai, or at least this representative, had a very very subtle flavor, and was a little chewer than I was expecting, so I gave it more marks for presentation than consumption, but nevertheless outstanding.

By contrast, what the teriyaki tuna cheek lacked in presentation it made up for in abundance in the eating. I could have eaten this every night for a month. A sort of Japanese spare rib, the meat literally fell off the bone, and in fact that was the sport: using one's chop sticks to poke and prod at the crevaces, it rapidly became something of a competition to see if you could find something the previous guy had overlooked. Absolutely delicious, succulent, flavorful, OMG good.

By contrast, what the teriyaki tuna cheek lacked in presentation it made up for in abundance in the eating. I could have eaten this every night for a month. A sort of Japanese spare rib, the meat literally fell off the bone, and in fact that was the sport: using one's chop sticks to poke and prod at the crevaces, it rapidly became something of a competition to see if you could find something the previous guy had overlooked. Absolutely delicious, succulent, flavorful, OMG good.

In amongst these were also garlic tuna steak, tempura, eel wrapped in egg, eel, octopus, salmon, and ugly shrimp sushi, and copious quantities of sake and shōchū. A Royal feast. But we were not done yet.

Next up came the miso soup and rice. Instead of the usual miso soup mix (an art in itself as we will discover tomorrow) this time the miso was hand-made from a stock created from the debris discarded by the sushi chef as he prepared our feast.

Finally the waiter brought this cake, which had clearly been one of the items Maiko-chan had been carrying to the restaurant. The other item was a present for me: a very nice bottle of sake. I know it was nice a) because that's the kind of people they were, and b) because when I got home, I got a few friends together and we did a tasting with a couple of other bottles. They did not know which was the local purchase, and which was the gift, but we were unanimous that the the gift was the superior bottle which I suspect means that it was very nice. Thank you!

Back to the challenge in hand, the waiter had brought the lit cake, but nothing to serve or eat it with. This left Maiko-chan with something of a dilemma: to point out that we needed something obvious like a spoon or a fork would have caused them loss of face—they made an error in not bringing them in the first place. So she says "I have to ask for something that functions like a spoon." As I recall they brought out melon spearers or something. They had just enough blade to work.

We staggered home. If Alistair and Maiko-chan had lived in a house with sliding paper doors and nothing but tatami mats on the floor, I think I would have died and gone to heaven. But of course they did not, that would have to wait for the Nakasendo. It was a western-style apartment, but still very small at least by American standards (but then what isn't?), and still had a distinctly Japanese character. The area inside the door had a different floor covering, and plenty of low shelves for switching from outdoor shoes to indoor slippers. We just went in bare feet. The kitchen was small enough that the dishwasher was a little unit that sat on the draining board. On the balcony, a set of drying stands had giant cloths pegs clipped to them, clearly big enough to even pin down a duvet and prevent it from blowing away.

We staggered home. If Alistair and Maiko-chan had lived in a house with sliding paper doors and nothing but tatami mats on the floor, I think I would have died and gone to heaven. But of course they did not, that would have to wait for the Nakasendo. It was a western-style apartment, but still very small at least by American standards (but then what isn't?), and still had a distinctly Japanese character. The area inside the door had a different floor covering, and plenty of low shelves for switching from outdoor shoes to indoor slippers. We just went in bare feet. The kitchen was small enough that the dishwasher was a little unit that sat on the draining board. On the balcony, a set of drying stands had giant cloths pegs clipped to them, clearly big enough to even pin down a duvet and prevent it from blowing away.

Over the balcony the railway line ran very close, and when the first train of the morning came by at about 6am I thought it was coming through the open window. I had no trouble falling back to sleep though, the night had been too short. When I finally did get up I was still the first to stir, so I sat out on the balcony, watched the trains, and this old man carefully tending this tiny plot of what would otherwise presumably have been wasteland. But nothing is wasted here.

Let the record show that Alistair and Meiko-chan were all around, hands-down, perfect host and hostess, and I will never forget their generosity and their kindness. When we returned for one final nightstop after the Nakasendo, they took us to yet another great restaurant, and then to an amazing whiskey bar that I describe in the discussion on Bars.

But before we leave the subject of wining and dining, I would be remiss if I did not discuss the meal that Meiko-chan prepared for us using the Hida beef she bought in Takayama. Of course this dish had a name, and I forgot to get it written down. The basic idea was this: everybody got a bowl, a steep-sided thing like a giant teacup. We cracked a raw egg into it. Meanwhile, Meiko-chan had a large cast-iron pot in front of her, sitting on a hot-plate. There was either nothing or just a few herbs/spices in the pot to start with. Then she lay a strip or two of the Hida beef in the bottom to seer it. She turned it over for a few seconds, and dropped the result into someone's bowl. We fished it back out again and ate it. And so it went around, kinda like a parent bird bringing food back to the gapping-mouthed chicks. Of course as we went along, out eggs got a little more cooked, and both in the cooking pot and in our bowls, a very tasty soup was starting to build up. When there was enough of this stock, Meiko-chan threw chopped up vegetables into the pot where they could steam for a minute or two in the stock. Again,I'm woefully ignorant of the vegetables, but I did watch her prepare them and noticed that most if not all of them were unfamiliar.

Now as you know, I have a very high tolerance for eating and drinking, and while of course I have my favorites, I will try pretty much anything, and can digest pretty much everything. But there are two things that I really cannot do: milk and raw eggs. Don't know why. I had done a fabulous job at overcoming the egg thing so far, but I'd reached the end, and after all the incredibly delicious, but incredibly rich beef, I was really looking forward to the greens, and knew that I couldn't cope with dropping them in my egg. I poured my "miso" into Adam's bowl. No one had a problem. Of course they didn't. I wished I'd simply had the heart/nerve not to crack the egg in the first place, but no harm done. I needed to try it the way it was supposed to be done before I started making adjustments. The fried/steamed greens were served, and hit the spot, spiced up with pot's miso, and some other splashes, dashes and pinches than Meiko-chan had added. What a feast, and again, the whole experience was just fab. Meiko-chan tried to get us to go back to the beef, but we were stuffed to bursting. Washed down with shochu, tired from the day of walking, all anybody wanted to do was roll over onto the living room floor, chat a while, and fall asleep. Which is exactly what we did. I hope someone reading this can fill in the details for me. I really did not do the chef justice.

Hida no Sato (Folk Village)

I love travelling by train, it is by far my favorite form of transport. But after a week of nothing but trains and the occasional local bus, the freedom of departure time and destination afforded by Alistair's Toyota "Clown" was an immensely enjoyable luxury. We just sat in the back and watched the world go by. And of course it was a different world too. They drive on the left, making the UK feel not quite so out-of-step, and on the whole drivers seemed safe and curteous. No wonder with the number of cautionary signs, and even ads on the radio every few minutes, urging one to do something, or not do something else "for the safety" as Adam and Alistair regularly called out, often in unison. Two cops wafted by in their cruiser, and they were wearing crash helmets, yes inside the car.

We talked about how few older cars there were on the road. Alistair explained that after 11 years, taxes on cars increase 10% per year, encouraging folks to get them off the road. But perhaps this all fits with a culture that seems to be at peace with the idea of renewal, from the 25 year half life of the property on a piece of land, leading to house prices dropping with the passage of time, instead of improving, to the repeated reconstruction of treasured historical buildings, and of course the amazing stoic determination to rebuild everything after events such as 2011's Tōhoku earthquake and Fukajima nuclear disaster, and countless others before that. "It's what we do."

We had left the itinerary for the weekend in Alistair and Maiko-chan's capable hands, and for Saturday they chose Takayama. This was inspired, because although it was on my list, I'd abandoned it to the B-list on the grounds that it was too far off our beaten track. But it occupied a double-spread in Eyewitness Travel, which made it pretty important.

We had left the itinerary for the weekend in Alistair and Maiko-chan's capable hands, and for Saturday they chose Takayama. This was inspired, because although it was on my list, I'd abandoned it to the B-list on the grounds that it was too far off our beaten track. But it occupied a double-spread in Eyewitness Travel, which made it pretty important.

Since I knew it was in the same general vicinity as the Shokawa valley, which featured another highly recommended attraction, a couple of villages with gassho-zukuri ("praying hands") houses (right) I asked if they knew anything about them. Alistair said no, but he thought there was some sort of open air museum that had old houses like this right on the outskirts of Takayama so we could try to find it.

For a few seconds we caught a long glimpse of Iwazaki castle (or was it Gifu?) which I recognized from my guide book, but it was gone before could even lift my camera.

He shoots, he scores: not only did Alistair find it (Hida no Sato) but it did indeed include several gassho-zukuri houses, and not only that, being a museum we were able to look around them inside and out!

Hida no Sato 飛騨の里 (Hida Folk Village) is an exhibit of over 30 traditional houses from the Hida region, the mountainous district of Gifu Prefecture around Takayama. The houses were all built during the Edo Period (1603 - 1867) and were relocated from their original locations to create the museum in 1971.

In this village-like atmosphere, the museum features a number of gassho-zukuri farmhouses. These are massive farmhouses named after their steep thatched roofs which resemble a pair of hands joined in prayer ("gassho"). They were moved here from nearby Shirakawago, (one of the villages in the Shokawa valley I had mentioned) where the gassho-zukuri houses are the reason for the region's World Heritage status. The village is built on a hillside overlooking the Takayama Valley and surrounds a large pond.

By the Goami pond a bread stand invited one to donate about 50c and take a small baguette of bread with which to feed the koi. I swear they could hear the coins drop in the box because within seconds fish from as far way as that swan were making wakes as they steamed towards us. Within a minute the water at our feet was a broiling mass of fish.

|

We set off on the longest route, the 1 hour course. There seemed to be no rhyme nor reason to which of the buildings were open, which we could wander into, and which had some artisan toiling away inside. So every building was a surprise. Before long we came to Wakayama's house, which the brochure conveniently identifies for me as one of the gassho-zukuri (合掌造) houses I've been looking for. |

|

Gassho-zukuri is one style varient of minka, homes for non-samurai castes. They have vast roofs that are a large form of the sasu structural system, which is a simple triangular shape with a pair of rafters joined at the top to support the ridge pole. The ends of these rafters are sharpened to fit into mortice holes at either end of a crossbeam. I neglected to record any of this in pictures, though I did get one (below left) of the straw rope used to replace nails in the construction. As this system does not rely on central posts it leaves a more unobstructed floor plan.

Gassho-zukuri is one style varient of minka, homes for non-samurai castes. They have vast roofs that are a large form of the sasu structural system, which is a simple triangular shape with a pair of rafters joined at the top to support the ridge pole. The ends of these rafters are sharpened to fit into mortice holes at either end of a crossbeam. I neglected to record any of this in pictures, though I did get one (below left) of the straw rope used to replace nails in the construction. As this system does not rely on central posts it leaves a more unobstructed floor plan.

I think this open floor served to give the obviously old house an ambiguously modern feeling inside. One could almost imagine living here, until one noticed the total lack of plumbing. The upper floors of the two and three storey houses are used for sericulture (silk farming), with storage space for the trays of silkworms and mulberry leaves.

Fires lit in the “irori” (sunken hearths) every morning not only keep the houses in good condition but also creates a peaceful atmosphere. So says the literature. More important by far in my book is the sense of life it breathes into the room. It turned the house into a home instead of a still life preserved in a museum.

|

|

|

The stairs were a tree trunk leaning in the stairwell, with steps hacked out of the upper surface. Adam and I spent some time putzing about upstairs and down, taking pictures of anything there was enough light to capture—many things did not.

|

I think this was a woodshed. It is the same roof through the window in the photo above right. On the right here is looking straight up the thatch of Wakayama's house again. Reminds me of many a roof in the UK, except there you never see those odd pins sticking through the roof ridge. I assume they anchor it, I'm just used to these pins being flush with the roof. |

|

Below left is Maida's House and to the right is the "wheel-shaped rice field." Apart from naming them on the map, the brochure says nothing more about either other than the fact that the rice planting in May, and reaping in September are "Events". So I fed "wheel-shaped rice field" into Google and this is what it returned: "Rice harvesting in kurumada, wheel-shaped rice fields. The method of planting rice plants concentrically around a rod standing at the center of the rice paddy is a very rare method in Japan and is a unique method developed in Hida." Another great explanation of everything and nothing. Why do it? Is it symbolic? Practical?

The bell isn't mentioned at all, not even as a label. Below right is Yoshizane's house (left) and Tomita's house (right) over the roof of "paper making" About Yoshizane's house the brochure bursts with information: "only this house in the village avoided collapsing down when the big earthquake ocurred in 1858. It is said that 'the forked pillar' used in the house prevented it from a big damage."

|

|

|

Below left is nearly the same shot again, this time with Alistair and Adam in front of Tomita's house. And the last picture I just like. But I can't for the life of me place it anywhere on the map. Not even the sequence number of the photo helps—it is after the one on the left, and the houses in the left photo are definitely two of the last houses on the tour ...

And so on to Takayama. Eye-witness Travel: "Its isolated mountain location has meant the survival of un-spoiled Edo-period streets lined with tiny shops, museums and eating places, while the pure water is ideal for sake brewing." It is where Japanese TV crews congregate to broadcast the first snows of winter because it has the reputation for being "the snowiest place in Japan."

But Alistair and Maiko-chan had an ulterior motive. Takoyama is in the Kobe region, and if Kobe is famous throughout the world for its beef, in Kobe itself, Takoyama is where you go for the best of Kobe. If I've done my research correctly, the beef was actually called Hida (and yes, I'm sure it's not a coincidence that this is also the name of the folk village) and I'm sure Maiko-chan actually bought Hida-gyu, known as one of the finest quality varieties of beef, meeting every standard, and of the highest quality in marbling, luster, color, texture and smell. Perhaps she bought several grades, but this was one of them. It certainly took a lot of careful selecting. Apart from the distinctive meaty smell, the transaction was much more akin to selecting a piece of jewelry than a regular purchase at the butcher. Which perhaps it was. Just like gem hunting, we wandered passed several stores peering at their wares before Maiko-chan finally settled on the one she wanted.

But Alistair and Maiko-chan had an ulterior motive. Takoyama is in the Kobe region, and if Kobe is famous throughout the world for its beef, in Kobe itself, Takoyama is where you go for the best of Kobe. If I've done my research correctly, the beef was actually called Hida (and yes, I'm sure it's not a coincidence that this is also the name of the folk village) and I'm sure Maiko-chan actually bought Hida-gyu, known as one of the finest quality varieties of beef, meeting every standard, and of the highest quality in marbling, luster, color, texture and smell. Perhaps she bought several grades, but this was one of them. It certainly took a lot of careful selecting. Apart from the distinctive meaty smell, the transaction was much more akin to selecting a piece of jewelry than a regular purchase at the butcher. Which perhaps it was. Just like gem hunting, we wandered passed several stores peering at their wares before Maiko-chan finally settled on the one she wanted.

The main objective complete, we could now turn our attention to the second order of business: touristing. We contented ourselves with a wander up and down the main drags rather than seeking out the museums and temples, but these old shops and eating places were really the major draw anyway.

|

The sugidama ball hanging next to Alistair's head tells us that this is a sake brewery. Sugidama originated in the Edo Period (1604 to 1868), and have taken many shapes and sizes over the past centuries, sometimes appearing more like bales or bound stalks of thin branches. As the pictures here show, they are always spherical these days. Also known as sakabayashi, they are balls constructed of the needle-like leaves of the sugi, or Japanese cedar tree. The sugi holds religious significance in the Shinto religion, particularly in connection with a shrine named Miwa Jinja in Nara Prefecture, wherein resides a deity related to sake. Although today not all sugidama are made from sugi boughs from this shrine, it is still one traditional source. Naturally we had to go in. There was a beautiful sunny courtyard behind the shop front, with few people in it, but we guessed this lack of popularity might have been because there was quite a steep price for sampling. I'm not saying it would not have been worth it, it seemed like there was some ceremony around it which would have been fun, but this all implied a little too much of a time commitment for this trip. First time we'd ever let that happen, but we were surely taking cues from our hosts, and we were very comfortable taking their lead. Instead I bought two of the square cedar box drinking vessels which served not just as a souvenir of Takoyama, but as a permanent reminder of the glass-in-the-box experience in Hiroshima. |

|

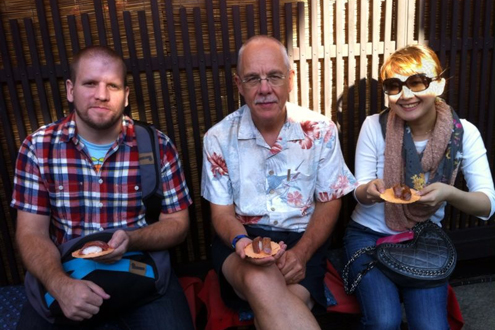

We were less able to resist the next temptation: beef sushi. Another first: there was a line. A woman sat in a little kiosk that seemed only just big enough for her to sit in. She made the little rice blocks by hand, then taking a strip of raw beef in one hand, she used the other to pick up a blow torch and waved its flame over the floppy beef strip, a couple of seconds each side. She laid the rice block on a disk of rice cardboard, then laid the strips of barely-scorched meat along the top. Done. That's us with our fare below right.

Notice the plate, which is rice-cardboard. So you can eat it, or if you throw it away, something else will eat it, or if nothing eats it, it will rot/disolve in days or weeks. A tad difficult to eat because it is two big for one mouthful, I ate the first strip on its own, and then the second one with the rice. The first mouthful was therefore just a delicious strip of beef, the flame having been enough to make the juices run, but the tangy flavor of the raw steak coming right through. For the second mouthful, there was the delightful sharp flavor of the sushi rice, but my mouth was still expecting it to accompany some sort of fishy flavor, despite the warning from the first mouthful. Very easy to get used to though.

Notice the plate, which is rice-cardboard. So you can eat it, or if you throw it away, something else will eat it, or if nothing eats it, it will rot/disolve in days or weeks. A tad difficult to eat because it is two big for one mouthful, I ate the first strip on its own, and then the second one with the rice. The first mouthful was therefore just a delicious strip of beef, the flame having been enough to make the juices run, but the tangy flavor of the raw steak coming right through. For the second mouthful, there was the delightful sharp flavor of the sushi rice, but my mouth was still expecting it to accompany some sort of fishy flavor, despite the warning from the first mouthful. Very easy to get used to though.

Another store seemed to sell nothing but miso mix. Two giant vats were in the middle of the store, and the shelves and table tops seemed to be covered in a huge range of sizes from ounces to gallons. They were handing out micro-samples from each of the vats. They were remarkably different. I asked how how they would keep, and the question seemed to phase them but I couldn't tell if they were wondering who keeps it long enough to care, or if like ketchup or hot sauce, it basically has an infinite shelf-life. "Six months?" was the vague reply. I bought about a pint of the darker flavored one. A good number of months after opening it, it's still as good as new, so I'm going with the infinite option.

I think this was the only time we saw a rickshaw with a passenger. And boy, did she look right at home in it. The top of the main drag was a T-junction where this second rickshaw begged to be photographed. From there we wandered across "the red bridge." Images of the bridge litter the interweb, from multiple view points and in multiple seasons. But not once is it given a Japanese name. It is not listed on my brochure either. Why there is so little to say about it is just another mystery. |

|

Last stop on the way home was Misen, a McDonalds-like Formica table and flourescent lighting kind of place, doing a frantic amount of business. The waitresses were literally running everywhere, and we had to wait twenty minutes for a table.

Maiko-san ordered a bunch of things again, water spinach, squid balls, "chinese" dumplings, but excellent as they were, they were eclipsed by the Taiwan ramen. By far the hottest dish we ate in Japan, and one of the hottest I've eaten anywhere. A real endorphin rush. Some of us were sweating quite profusely. Naming no names. Alistair.

Maiko-san ordered a bunch of things again, water spinach, squid balls, "chinese" dumplings, but excellent as they were, they were eclipsed by the Taiwan ramen. By far the hottest dish we ate in Japan, and one of the hottest I've eaten anywhere. A real endorphin rush. Some of us were sweating quite profusely. Naming no names. Alistair.

Meiji-Mura

Sunday's destination was Meiji-Mura, just outside Inuyama, which in turn is not far from Nagoya, so a much shorter trip this time. Meiji-Mura is an open-air architectural museum/theme park. It was opened on March 18, 1965. The museum preserves historic buildings from Japan's Meiji (1867–1912), Taisho (1912–1926), and early Shōwa (1926–1989) periods. Over 60 historical buildings have been moved and reconstructed onto one square kilometre (250 acres) of rolling hills alongside Lake Iruka.

Sunday's destination was Meiji-Mura, just outside Inuyama, which in turn is not far from Nagoya, so a much shorter trip this time. Meiji-Mura is an open-air architectural museum/theme park. It was opened on March 18, 1965. The museum preserves historic buildings from Japan's Meiji (1867–1912), Taisho (1912–1926), and early Shōwa (1926–1989) periods. Over 60 historical buildings have been moved and reconstructed onto one square kilometre (250 acres) of rolling hills alongside Lake Iruka.

Nine of the buildings are designated as Important Cultural Assets, and nearly all the rest are registered as tangible cultural assets. That makes sense, and that alone would seem to make the project worth doing. But the museum also includes buildings from Hawaii and Seattle in the United States, and also Brazil. That seems to make less sense to me.

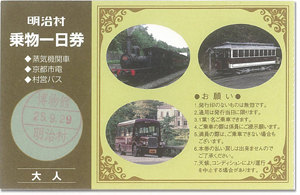

Three modes of transport are available in the park, and the most expensive ticket allows you to ride on all of them, which is definitely part of the fun. One terminus for the steam locomotive was right outside the ticket booth, so that seemed a logical place to start, but there was also a street car, along with shuttle buses and apparently horse-drawn carriages, though we saw hide nor hoof of these.

Three modes of transport are available in the park, and the most expensive ticket allows you to ride on all of them, which is definitely part of the fun. One terminus for the steam locomotive was right outside the ticket booth, so that seemed a logical place to start, but there was also a street car, along with shuttle buses and apparently horse-drawn carriages, though we saw hide nor hoof of these.

We waited a few minutes for the engineer to prepare the engine, giving us a chance to watch it chuff out of its shed, overtake the carriages and then be backed up and coupled to the front of the train. We all piled on for the two minute ride to the other end of the line, about half way down the park. From there we jumped on a bus to take us all the way to the bottom. Total distance traveled perhaps half a mile, but probably less. It was a strange place. No question that it is an open air museum. But other museums designed to preserve buildings of cultural or at least historical significance, such as Beamish in the north of England, or Sturbridge Village in New England somehow manage to take you back in time. They feel like real places, whereas this was just, well, a museum. A bunch of buildings collected together but no sense of belonging together.

Which isn't to say we didn't have a good time wandering in and out of the various buildings. Often there was an exhibition inside, in which case there was a connection. For example in the old telephone exchange each room featured telephone equipment from a different era. Another building was furnished, decorated, and set out ready for a formal dinner as if the guests had all just fled when they heard us coming. But for some reason, three buildings in particular stood out for me: St John's Church; Shinagawa Lighthouse and the adjoining Keepers cottage (though this seems to be from a different lighthouse); and the Main Entrance Hall and Lobby from the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Including the telephone exchange these represent four of the nine Important Cultural Assets, and the only one that was not was Frank Lloyd Wright' Imperial Hotel which was not only best of show for me, but is the only one featured in the brochure?

|

|

|

St. John's Church from Kyoto (1907) designed by James McDonald Gardiner was built as an Anglican Church. The first floor is brick, the second floor wood, and the roof is tiled with sheet copper. Apparently "these are ingenuities make the church quakeproof." They definitely give it great style. Its brick exterior is a beautiful blend of Romanesque and Gothic design, the interior features distinctively Japanese designs appropriate to Kyoto’s climate, such as the "bamboo blind in the ceiling." The dark brown bamboo ceiling and wooden clustered columns provide a distinctly Asian atmosphere. The interior shot below, shamelessly stolen from Ginkgo Telegraph shows the "bamboo blind" ceiling really nicely. It was way too dark for me to even attempt to get a shot.

|

At the end of the line, like any other trolley, the trolley pole must be unhooked, walked around to the other end of the car, and hooked back onto the line. I'd never actually seen that done before, so that was excellent. Some settings seemed more natural than others, but this house looked quite at home in its surroundings. I can't identify it however. |

|

|

Maiko-chan said this was a favorite of hers. The vendor cracked an egg onto his hot plate, then used a wide spackling blade to smear the egg out into a thin layer. He added a spoonful of pickled ginger, something spicy, and mayonaise. After folding the oval over into a semi-circle, it was placed onto one side of a rice-cardboard plate. He used his spackling knife to press a crease across the middle of the plate, then folded it over the egg, creating a sort of Japanese taco. Wrapped in a napkin, it's yours. God knows what happened if there was a line because he was slow, methodical, and somehow made it clear that there was absolutely no way to speed the process up, no matter how aggrevated the line was getting. As usual: delicious. |

|

For no reason that I could figure out, this young girl was just sitting in an open doorway. There was no way I could interpet it as anything other than posing for the camera, especially with her stone cat. Other folks were taking her picture. I had no choice.

The Kureha-za Theatre was another important cultural property, taking my total count to five out of nine. Not bad considering there were 67 structures to choose from, and I was not looking for them, I was just taking pictures of structures that drew me to them. It looked like we had just missed a performance, but especially if we hadn't, it was a nice touch to make it feel that way.

But for me,we saved the best for last, the reconstructed main entrance and lobby of Frank Lloyd Wright's landmark Imperial Hotel, which originally stood in Tokyo from 1923 to 1967, when the main structure was demolished to make way for a new, larger version of the hotel. It took 20 years to move and rebuilt brick by brick, and though only the entrance and lobby remain, it is the largest structure in Meiji Mura. Wright traveled to Japan in 1905. Japan was emerging from centuries of isolation into the modern world, and the committee in Tokyo wanted a forward-looking design for the hotel that would represent the emergence of Japan as a modern nation and symbolize Japan’s relation to the West. Wright had long been intrigued by Japanese culture (he was an avid collector of Japanese prints), so when the opportunity came he lobbied for the Imperial Hotel project. Japanese friends and colleagues recommended him as architect to the committee. Commissioned in 1916, Wright designed the building as a hybrid of Japanese and Western architecture. Designing and building the hotel took eight years, during which Wright traveled between Japan and America. Wright designed the building around a central courtyard with a reflecting pool so that the hotel rooms would have a lovely view and the guests would feel isolated from the city around them. Wright found that Japan had a type of soft lava stone called Oya that could be carved with very intricate patterns, and he used it throughout the entire structure. Wright created impressive spaces to emphasize the exclusive nature of the hotel. The central lobby was three stories tall. The dining room and ballroom were each two stories tall. I loved it. |

|

|