Hermit of the Jungle

A day in the life | Settlers | Hermit | Tapioca/Cassava | Meeting of Waters | Lists | Manaus | M/Y Tucano | Ecology | Maps

Back in the spring, Brian sent me an interesting article from the New York Times, entitled ‘Hermit of the Jungle.’ We wondered where the Hermit might hang out in relation to where we were planning to be? He could quite easily have been a thousand miles away, or less than a thousand yards, and we would have had no way to tell the difference. I might have put the article out of mind, but I never forgot the photograph from the article (below) and how much it reminded me of a (real life) Indiana Jones movie set.

Imagine our surprise and delight to find the canoes edging up to the ruins we clearly remembered from the article. Where the hermit, Shigeru Nakayama, is standing, he would now be up to his crotch in water, because as we pulled up the water was lapping against the top step.

Remembering the Times photograph, it was like seeing the movie and now finding yourself on the set.

Imagine our surprise and delight to find the canoes edging up to the ruins we clearly remembered from the article. Where the hermit, Shigeru Nakayama, is standing, he would now be up to his crotch in water, because as we pulled up the water was lapping against the top step.

Remembering the Times photograph, it was like seeing the movie and now finding yourself on the set.

Airão was once a village of medium importance, then named St. Elias do Jaú. It was founded by missionaries in 1694, the first town on the banks of the Rio Negro. Missionaries went about competing for souls here, delivering sermons to indigenous people in a stone church for the better part of two centuries.

Before Brazil gained its independence in 1822, the authorities in distant Lisbon changed the name of the settlement to Airão, which persisted on maps as a tiny dot on a vast frontier—1000 miles from the coast, and only whatever there was to Manaus in between. In the mid-nineteenth century the rubber trade started to pick up with a vengeance, and this is where Souza’s story picks up.

|

|

|

Francisco Bizerra was basically a human trafficker, aka slave-trader. Using debt bondage he provided “volunteers” with a loan to pay for transporting them out to Airão and to set them up. The worker of course is expected to “work off” the loan, but in practice, the amount owed continues to grow over time, and the loan can never be repaid. He did this by paying minimal prices for the latex and pelts the workers brought back to the town, and charging high prices in his store. To make sure you had no chance, there was never any cash: every transaction was just a debit or a credit in the company ledger, and because the workers could not read, it was easy to cook the books. One worker who could read, and kept his own copy of the account, finally insisted on being paid in cash for what he was owed. He was given the cash, but the story goes that he never made it out of the jungle.

Francisco Bizerra was basically a human trafficker, aka slave-trader. Using debt bondage he provided “volunteers” with a loan to pay for transporting them out to Airão and to set them up. The worker of course is expected to “work off” the loan, but in practice, the amount owed continues to grow over time, and the loan can never be repaid. He did this by paying minimal prices for the latex and pelts the workers brought back to the town, and charging high prices in his store. To make sure you had no chance, there was never any cash: every transaction was just a debit or a credit in the company ledger, and because the workers could not read, it was easy to cook the books. One worker who could read, and kept his own copy of the account, finally insisted on being paid in cash for what he was owed. He was given the cash, but the story goes that he never made it out of the jungle.

As Souza told the story, we were buzzed by some wasps which were only noticeable because it was so unusual. Claudia was rightly paranoid about wasps, what with her anaphylaxis and all, and because she was nervous, I was too, so I watched them intently, willing them away from her, and not caring where else they went. So I was focused on her small flock when without thinking I put my hand up to scratch an itch in the corner of my eye, and I was immediately stung for my trouble. I didn’t dare say or do anything, and amazingly, it never swelled up or even turned red. After 15 minutes or so the pain eased and the incident was therefore forgotten.

That was the end of Souza’s story, but here’s a brief description of how we got from then to now. Hundreds of people are thought to have lived here at the outpost’s height, as the New York Times article puts it “strolling down cobblestone streets past imposing colonial-style trading houses, shops and municipal buildings, shielded from the tropical deluges under roofs made of Portuguese tile.” This is hard to reconcile against Souza’s darker story, but I suppose it is possible that there is some sort of middle ground.

Like Manaus itself, when the rubber trade collapsed in the first half of the 20th century, so did Airão. Now called Airão Velho, because the departing families had started Novo Airão further down the river towards Manaus, a few families tried to repopulate the city. A schoolhouse for children from nearby communities offered some vitality to Airão Velho.

|

|

|

In 1985, the Brazilian Navy began using the abandoned city as a target for bombing practice. In 2005, the city was listed by the Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute National IPHAN, ending the bombing. I’m not sure what it says about the Brazilian Navy that after 20 years of bombardment, some of the buildings are still standing. Worst Wikipedia entry ever (or at least as translated): “Since 2005 about seven families returned to the village, making their homes around the ruins and help in the execution of tourists visiting the old village.” Around that time, Gloria Bizerra, a descendant of the Bizerra clan, asked Mr. Nakayama to care for the abandoned outpost.

So he was still here, and we were going to meet him! How cool was that? Not so fast. The path to the “village” was waterlogged, but Edi and Souza knew of a back way to the village. The canoes pulled away again and came ashore about 100 yards further back. This gave us an opportunity to examine and discuss a rubber tree with the scars made by latex collection, before making our way along the sandy path to the cemetery. I was not the only one who noticed a sort of voodoo vibe to the place, helped considerably by the clearly recent grave of Gloria Bizerra, marking the final end of the evil empire, and providing all-too-real hard evidence to back up Souza’s excellent but otherwise rather fanciful tale.

|

An attractive morning glory-like vine was flowering over a trail-side bush. "Clitoria" says Souza. The small group within ear-shot exchanged fertive glances. "Whatever you are thinking ... " Souza says, pausing for dramatic effect "... you are probably on the right track." The more brazen members of the crowd stepped in to take a closer look, others looked like they wanted to. "It is one of many flowers that change color when they have been pollinated." Sure enough, the next time we came across a patch of it while out in the canoes, all the buds had developed a lovely purple blush (right). |

|

Just as we approached the main compound, we came to a cacao tree. I can’t resist a small rathole: unusually, the flowers (and therefore the fruit) are produced in clusters directly on the trunk and older branches, and here’s the fun part: this is known as cauliflory—you can't make this stuff up.

Just as we approached the main compound, we came to a cacao tree. I can’t resist a small rathole: unusually, the flowers (and therefore the fruit) are produced in clusters directly on the trunk and older branches, and here’s the fun part: this is known as cauliflory—you can't make this stuff up.

One of the fruit pods was ripe and easily accessible, and Edi cut it down, then deftly scored around the middle so that he could pull the top half off the pod off like a cap, leaving the seeds (don’t start all that again), okay, beans still embedded in their white pulp. Waste not want not, this pulp is edible, so of course we ate it (meh) but apparently it has recently started to be harvested for fermenting into a fashionable new liquor. Another project.

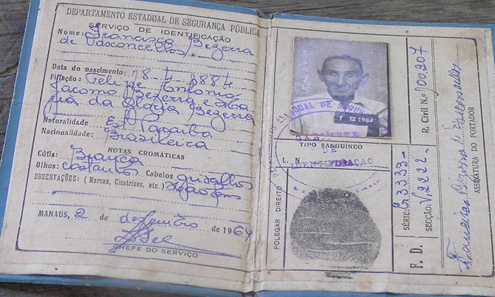

Then on to meet and greet Mr. Nakayama, who started out by taking us on a tour of his “museum.” He invited us in to the hovel with dirt floors where he lives. A faded poster on the wall near the entrance, which features a brunette in an animal-print bikini and grasping a spear while astride a tiger, hangs alongside a road map of Brazil (though this heavily forested region has almost no roads; boats provide most transportation). An oil painting in his museum depicts what Airão Velho might have looked like in its heyday during the Amazon rubber boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when the settlement emerged as a busy hub for rubber tappers and traders. But the prize in his collection, in my humble opinion, is Bizzera’s passbook.

Then on to meet and greet Mr. Nakayama, who started out by taking us on a tour of his “museum.” He invited us in to the hovel with dirt floors where he lives. A faded poster on the wall near the entrance, which features a brunette in an animal-print bikini and grasping a spear while astride a tiger, hangs alongside a road map of Brazil (though this heavily forested region has almost no roads; boats provide most transportation). An oil painting in his museum depicts what Airão Velho might have looked like in its heyday during the Amazon rubber boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when the settlement emerged as a busy hub for rubber tappers and traders. But the prize in his collection, in my humble opinion, is Bizzera’s passbook.

|

|

|

The compound was well cared for. Mr. Nakayama clearly relished receiving visitors as we were all invited to sign his detailed visitor’s book. His resilience and enthusiasm helped to make the place feel like a lovingly tended historical site, blowing away my earlier sadder feelings of neglect and loss as I stared at the soccer field with only one person to play on it, or the old school house with writing still on the board as if the children had only gone for lunch instead of gone for a generation.

“I’m glad there’s someone taking care of Airão Velho,” said Victor Leonardi, a historian of Amazonia at the University of Brasília who explored the ruins here in the 1990s. “It smelled of jaguar urine back then, but it was obviously a place of riches at one point, where people dined on porcelain from England and consumed Cognac from France.”