Ecology

A Day in the life | Settlers | Hermit | Tapioca/Cassava | Meeting of Waters | Lists | Manaus | M/Y Tucano | Ecology | Maps

The reason this page is here is because pretty much everything else about the geography and ecology came as a surprise to me. Also this seemed like a perfect place to showcase Claudia's fabulous collection of flora details. All the pictures on this page are from her collection.

In temperate climes, we are used to something of a monoculture: beech woods, pine forests, aspen stands. Even the names imply that if you find a tree of one type, the odds are great that the next tree will be of the same type, and if it isn’t the next one is not far away. In Amazonia, it is extremely common for the next tree of a particular type to be miles away, and there will be hundreds of different types in between.

Although the zillion square miles of rain forest that make up the Amazon rain forest are all in the tropics, and are reasonably flat (so elevation differences do not play a big role until you get to the Andes in the far west), there are in fact a considerable number of different habitats.

First up, the world can be divided into blackwater and whitewater (not to be confused with a kayaker's whitewater rapids). The Amazon itself, because it starts in the foothills of the Andes (which are dissolving) gathers its payload of silt eroded from the relatively young, nutrient-rich soils in the Andean foothills and as a result of the silt is milky colored (white). The fast-moving current can carry large volumes of suspended material long distances. However, as the water slows down on its journey across the Brazilian plains eventually, inevitably, quantities of these soils drop out of suspension and form extensive flood plains. Successive floods and high waters pick it up and move it along. The abundant vegetation that grows in this rich soil needs to grow quickly and it produces a flooded forest community of species called varzea.

Meanwhile, the blackwater regions, most notably those of the Rio Negro watershed, have their origins in the nutrient-poor soils of the lowlands themselves. The same tectonic plate movement that is pushing the Andes skywards have exposed the Brazilian lowlands to long bouts of weathering and erosion. Not only have the ancient mountains long weathered away, but most of the nutrients such as phosphorous, nitrogen, and potassium have long since been leeched out, leaving nothing but white sand. This is in fact one of the oldest geological formations on earth. We can attest to the sand: kick away an inch or so of dead leaves, and there it was. And unlike temperate climates, where there is only a relatively short period each year when the bacteria, fungi and other soil organisms that make decomposition possible can be active, here this material is consumed immediately and so never gets a chance to build up into any sort of humus. This community is called igapo.

The silt-free water flowing in the igapo regions does not stay clear of course. The trees and shrubs in these areas, lacking the natural fertilizers that the whitewater rivers provide their forests, can only produce leaf material at half the rate of their whitewater cousins. Thus if a herbivorous insect eats a leaf of a blackwater-associated plant, it is in serious trouble. The destroyed leaf means that the plant has that much less photosynthetic surface, and it cannot be replaced quickly. Therefore the plants develop extra defenses to protect themselves, and a commonly used defense is the production of toxic chemicals, which make the herbivores sick or at least make the material significantly harder to digest. These toxins, mainly tannins and phenols, leach out of the leaves that do fall, and turn the waters of the surrounding streams and rivers the color of dark tea—no coincidence, since tea itself contains tannins, which is why tea is the color it is. By the way, in another indicator of the impoverished environment, deciduous trees can't afford to drop all their leaves at the same time (of course they don't have the problems of dealing with seasons either) but that's how deciduous trees are also green all the year around: they literally drop one leaf at a time.

Other adaptations include growing roots sideways instead of down--most roots in the forest are within 12 inches of the surface, allowing them to be ready as soon as whatever nutrients there are, are released. A high percentage of trees in the igapo also associate with ants, which bring in detritus and food particles to store in nests in the tree. This "garbage" breaks down and the tree can absorb it.

Both varzea and igapo are flood plains--in the rainy season they are underwater. The ground that is not flooded during the rainy season is aptly named terra firme, which naturally has its own ecosystem. Furthermore, it is easy to imagine how terra firme can, and does, exist as "islands" (some larger than others) separated by varzea or igapo areas.

Rathole within a rathole: Riparian forest This discussion would not be complete without a mention of riparian areas, zones, forests. Riparian references litter the material I used to create the background discussions (ratholes) on these pages, but all the actual definitions I found felt vague. They seemed to be describing something that could also be igapo or varzea without ever mentioning either of them, and therefore never allowing me to deduce the relationship between the three terms. Finally I discovered that the word "riparian" is derived from Latin ripa, meaning river bank. Many references had of course used the term, but generally in conjunction with weasel words like "adjacent" or "interface." So the riparian zone is extremely localized, focused as its name implies just on the river bank and its immediate surroundings. How narrow? Environmentalists in Brazil are trying to change some legislation that currently defines the riparian zone as anything within just 60 meters of the waters edge. Therefore any other ecosystem could easily include riparian areas within it. In fact that would be normal! I finally found a scientific paper that describes riparian forest as “azonal.” I rest my case. So riparian forest is yet another habitat to add to the complexity of the rain forest biodiversity. Despite this incredibly narrow footprint, riparian zones are frequently visually obvious (for example, trees lining the banks in an otherwise grassy landscape) and therefore it should be no surprise that they are ecologically important. Riparian zones are instrumental in water quality improvement for both surface runoff and water flowing into streams through subsurface or groundwater flow. The vegetation surrounding the stream helps to shade the water, mitigating water temperature changes. The riparian zones also provide wildlife habitat, increased biodiversity, and provide wildlife corridors, enabling aquatic and riparian organisms to move along river systems. The meandering curves of a river, combined with vegetation and root systems, dissipate stream energy, which results in less soil erosion and a reduction in flood damage. Sediment is trapped, reducing suspended solids to create less turbid water, replenish soils, and build stream banks. Pollutants are filtered from surface runoff which enhances water quality via biofiltration. |

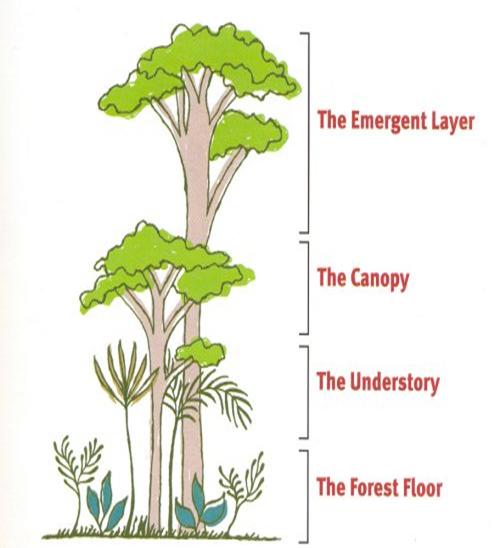

So far we've only talked in two dimensions. However the diversity happens vertically also, with four distinct layers: ground cover, the understory, the canopy and the giants of the emergent layer.

All this adds up to diversity on an unimaginable scale. On one 3 mile path in the western Amazon, lepidopterists found almost 1200 species of butterflies, (not including moths), many more than found in the whole of North America. |

From a single tree another biologist found more species of ant than occur in all of England. From the canopy of another tree a researcher collected 1 kilogram of insects and spiders, which contained nearly 2000 species, all but 100 of which were completely new to science.

The outside images are lianas, woody vines that start at ground level and use trees and other structures to support them as they climb towards the light, not always using the most direct route.

And this is where it starts to get really interesting.

A tree might be miles from another of its own species. With no summer and no winter, there is no good time to flower, fruit or breed: each to their own. So you need to be able to travel from one food source to another as it becomes available, or you need mutualisms and commensalism to help you out.

Two things become dramatically obvious: the vast majority of the nutrients in the environment are locked in the plants themselves, not in the ground. Second, any sort of monoculture (aka farming), would be a complete non-starter. Anything that grows here is totally dependent on everything else that grows and lives here for its survival. We keep not learning this. The majority of the deforestation is a result of earlier clearing, itself not three to five years old, now being incapable of producing a crop, and incapable of regenerating the forest, possibly ever, but certainly in less than hundreds, or even thousands of years. It therefore doesn't even make local sense, never mind planetary sense. Just a small handful of white guys getting rich at the planet's expense.

But to understand the area’s current diversity, we also have to look at the fourth dimension: time. Over the last 100,000 years or so there apparently have been ten-thousand year cycles of drought and heavy rainfall. These cycles may have changed some parts of this immense forest region by contraction and expansion of the geological ranges of different species of animals and plants. Some species less tolerant to climate changes may have become isolated, other species more tolerant may have become widespread. Because of the Andes Mountains and the shape of the continental coastline, rainfall across the Amazon Basin is not, and probably never has been, uniform.

Even today, in the middle of a high rainfall part of the cycle, small pockets of forest with 10 to 13 feet of annual rainfall can be surrounded by forest areas with less than 5 feet of annual rainfall. During the most severe drought epochs, annual rainfall totals were probably cut by a third or more. Some or even many species of plants and animals became isolated from their kin in contracting ranges. Isolated for tens of thousands of years, these populations evolved into different species and were no longer capable of breeding with members of their former species in other isolated areas. When the drought cycle shifted back to high rainfall, the isolated populations were again able to expand and reclaim areas in which they could now occur. Eventually the expansion of these species brought them into contact again with their long-separated kin. Where the expanded populations met, no longer able to breed together, the new species instead mixed, thus greatly enriching the diversity of the species.

Scientists are struggling with interpretations of data that show conflicting timing and positioning of these climatic events, and there is little agreement on the details. However, most scientists will agree that the forests of Brazil have not been static, and that changes, subtle and not so subtle have occurred over the last several hundred thousand years that have affected the present distribution of species and helped increase their number.

Rathole within a rathole: The Fifth Dimension

"The Ingano at Puerto Limón, for example, recognized seven types of yagé. The Siona, a neighboring tribe, had eighteen, which they distinguished on the basis of the strength and color of the visions, the trading history of the plant, and the authority and lineage of the shaman who used it. None of these criteria made sense botanically, and as far as Schultes could tell, all the plants were referable to one species, Banisteriopsis caapi. Yet the Indians could readily differentiate their varieties on sight, even from a considerable distance in the forest. What's more, individuals from different tribes separated by large expanses of forest identified these same varieties with amazing consistency." "While with the Ingano, [ ... ] Schultes made one of the most important and curious discoveries of his career. The preparation in question was ayahuasca, known also asyagé, the vision vine, the vine of the soul, the most celebrated hallucinogen of the Amazon. [ ... ] Sacred to all the tribes of the upper Amazon, it is the embodiment of the jaguar, a magical intoxicant capable of freeing the soul, allowing it to wander into mystical encounters with ancestors and animal spirits. Shamans maintain that under its influence collective visions occur and it is possible to communicate across great distances in the forest. Usually taken alone, but in Puerto Limón it is taken sometimes together with the bark of another vine—the chagropanga. It is said to be almost the same leaf, but a harder and stouter vine." "Here was evidence of pure empirical experimentation of a specificity he had never before encountered. [ ... ] Now his Ingano informants insisted that by manipulating the ingredients of the preparations, in this case by adding chagropanga, it was possible to change the nature of the experience. Schultes did not question the word of the Indians. Instead he elected to test their preparations for himself. " The rest, as they say, is history. |

Thanks to an incredibly generous gift by the Gourlies I am able to add this rathole gleaned from the pages of my very own copy of "

Thanks to an incredibly generous gift by the Gourlies I am able to add this rathole gleaned from the pages of my very own copy of "