A day in the life

A Day in the life | Settlers | Hermit | Tapioca/Cassava | Meeting of Waters | Lists | Manaus | M/Y Tucano | Ecology | Maps

5:20 am: Reveille ...

No trumpets, just Souza knocking on every door. I was impressed that everybody always got up, and no one ever seemed to complain, we just suited up, grabbed a coffee if there was time, and spilled into the canoes, or, on a couple of (voluntary) occasions, kayaks. The difference between an ecotourist and a regular tourist or a local is that the regular tourist/local must be protected from the weather no matter what the view, whereas the ecotourist must be able to view, no matter what the weather. So you can spot the ecotourists a mile off, because their transport has no canopy. Therefore the canoe was an open longboat, with just enough room for nine passengers and a pilot perched beside the outboard at the stern and a guide perched at the bow. Our seven plus two configuration was much more comfortable.

On the first day, Edi prepped us for the trip: "What do you call mosquitoes in the US?" Chorus: "Err, mosquitoes?" Edi (triumphant): "Here we don't have to call them, they come by themselves." Arf. But they did not come! The rumors were true: no mosquitoes on the Rio Negro. Claudia got more bites on the first day back in our own yard than she did during the whole time on the river. I think I set the record for bites and/or stings while we were there, and if that's not true then I certainly set the record for bites per second, but we'll get to that in due course.

I know this might be a bit of a shock, but in Amazonia it rains. A lot. Even though we were not in the rainy season, it rained pretty much every day, and often more than once, though thankfully the average length of a shower was ten minutes—give or take not very much—as we started to time them. I say shower, but it felt more like a deluge if you were caught in it, which we were once, and several times missed doing so by mere seconds. The other thing to note, while we’re on the subject of the “bleedin’ obvious” is that it is a forest. A big one. Day after day, two hundred plus miles and nothing but trees. And we were just scratching the surface (check out the maps). This is presumably why they call it a rain forest. The sheer volume of water is hard to comprehend. At Manaus the Rio Negro is about 5 miles wide, and the water level difference between the end of the rainy season and the end of the dry season is about 40 feet. Two hundred miles upriver, our canoes were still maneuvering through tree tops.

I know this might be a bit of a shock, but in Amazonia it rains. A lot. Even though we were not in the rainy season, it rained pretty much every day, and often more than once, though thankfully the average length of a shower was ten minutes—give or take not very much—as we started to time them. I say shower, but it felt more like a deluge if you were caught in it, which we were once, and several times missed doing so by mere seconds. The other thing to note, while we’re on the subject of the “bleedin’ obvious” is that it is a forest. A big one. Day after day, two hundred plus miles and nothing but trees. And we were just scratching the surface (check out the maps). This is presumably why they call it a rain forest. The sheer volume of water is hard to comprehend. At Manaus the Rio Negro is about 5 miles wide, and the water level difference between the end of the rainy season and the end of the dry season is about 40 feet. Two hundred miles upriver, our canoes were still maneuvering through tree tops.

I learned long ago that there are three ways that I’ll see a bird: if it is big enough; if it is colorful enough; if there is a large enough flock. It's better if I can get two out of three. There were plenty of contenders here, especially in the colorful category. For a catalog of all sightings, and any photographic evidence folks have shared, see the Lists page. Below I call out a few of my favorites. But first some vocabulary:

- Leaf parrot: A bird that on closer inspection (especially by a third-party) turns out to be a bunch of not-so-interesting leaves.

- Jungle pigeon: Any unidentified parrot. Very common until and unless a guide saw it too.

- Bush turkey: The unmistakable hoatzin, which we sighted so often they got a nickname, despite the many accounts we read about them being hard to find.

5:50 am ... Dawn Patrol

There’s no question that the dawn and dusk patrols yielded the most sightings, partly because more things are active at these cooler times of day, and partly because being out on the water there’s just so much more visibility than when walking among the trees. I loved the quiet of just floating along with only the occasional quiet splash of a paddle to ease us along.

Images courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015

The sound of the morning trips was the howler monkeys, or rather I should say monkey, singular. Only the pack leader howled, establishing his strength (of vocal chords if nothing else) and his territory. The guides estimated his distance from us as anywhere from 1 km (loud!) to 5 km (still totally audible). Aptly named, the noise was eerily like the wind howling around the house on a desolate moor one dark and stormy night. One kilometer or several, they were generally far too far away to be seen, though there were a couple of fleeting exceptions.

Images courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015

All eyes were on the trees, (below left) but some saw a lot more fauna than others, and Adam in particular gave the guides a run for their money. Perhaps more importantly, he rarely committed the sin of calling out leaf parrots, so when he piped up the guides paid attention. The rest of us scrambled to get our binoculars on the target before the inevitable “Oh! It’s gone …” Even the three-toed sloth, which National Geographic describes as “the world's slowest mammal, so sedentary that algae grows on its furry coat” had a way of moving out of the line of sight as we watched. It goes on: “All sloths are built for life in the treetops. They spend nearly all of their time aloft, hanging from branches with a powerful grip aided by their long claws. Dead sloths have been known to retain their grip and remain suspended from a branch.” But our favorite factoid was that despite all this, once a week they descend from the tree to defecate. It seemed like a lot of trouble to go to, when gravity would have done the job pretty effectively, but ya gotta do what ya gotta do.

|

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015 |

With the water level so high (above right) it was possible to get into the trees and float past the trunks. This was a good way to find sloths, but mostly on these daylight trips these sorties through the woods were taking a short-cut from one channel to another.

Yellow-crowned Brush-tailed Rat. Big name for a little guy. Image courtesy and © Claudia Mueller Thomson 2015 |

Sometimes this required machete work (right), but I often wondered how much of this was either because Souza loved the work, or because it was orchestrated to help the guests feel like we were truly in the heart of the jungle. Either way, it was on one such excursion that I lifted a particularly low-hanging branch to help us skim underneath and within seconds was rewarded with an armful of ants that gave me a couple of dozen bites before I could shed them. There were a few moments of squeeking and stamping behind me as some of my guests survived the brush off and set about exploring the rest of the canoe. |

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015 |

With peace more-or-less restored, I examined the branch more carefully and the ants were pretty obvious, so I was able to avoid making that mistake again.

The southern tamandua is a two foot long anteater that is common enough for us to be able to find one, but one is all we found, and as usual it was way way up in the trees. It moved slowly enough for us to be able to get a good look through binoculars, but between the distance and the intervening foliage, still photography shots were all but useless. As any self-respecting jungle-dweller knows, rule number one for becoming invisible is to be still. So something you can see clearly as it moves through and behind the twigs and leaves becomes all-but invisible again in the stillness of a photograph. We had better luck with this yellow-crowned brush-tailed rat (above left), who was snug enough in his hole that he let us get very close in the canoes. Apparently guarding the entrance to his den is a favorite spot for this little guy who we found exactly where Wikipedia says we would "at the entrances of their dens, in tree holes on the borders of rivers."

Apart from the monkeys, this small list was about it for mammals. I'm not complaining, or not much anyway. Unless they were swimming (which does happen, but would be extremely rare) the ground-based mammals would by definition not be visible from the canoes, and in the close quarters of the forest, and on foot, game animals would have been scary enough (for them and for us). To come face to face with a hunter, even a small one, was more or less unthinkable. So by far the most frequent, easy, and therefore dependable sightings, were birds.

Image courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015

Having gotten itself seen, I've now realized that my favorite birds all have one thing in common: they have character. Yes, anthrophomorphism. What's your point? This would definitely explain my affection for the hordes of parrots, especially the festive parrots which seemed to travel in pairs, squabbling back and forth as they flapped frantically to maintain altitude flying between committee meetings. I’m told it was just exercise, but when a perched parrot started to rock the branch up and down until it was moving so wildly that everyone else fell off, it was hard not to interpret that as pure mischief. Edi: "Richard!" "Yessir!?" "Who's making that noise?" "Err, parrots sir?" "Yes, yes. Parrots. What kind of parrots?" "Festive parrots sir?!" "Good." "Phew."

|

Rathole: Why are birds so conspicuous? Why are birds so much more conspicuous than other vertebrates--in general, but in the jungle in particular? The reason is simple: they can fly. The ability to fly is one of nature's premier anti-predator escape mechanisms, and animals that can fly well are released from the danger of being stalked by a large portion of the predators in the area. Most mortality from predators in tropical birds comes while they are eggs or helpless young in the nest. Once they reach adulthood, their mortality rate by predation falls to very low levels. By being able to escape most predation, they are released from much of the tyranny of natural selection that places a premium on camouflage, unobtrusiveness and shyness. Thus they can be both reasonably conspicuous in their behavior and also reasonably certain of daily survival. Most flightless land vertebrates, tied by gravity to moving in or over the ground or on plants, are easy prey unless they are quiet, concealed, and careful, or alternatively, very large and fierce; many smaller ones, in fact have evolved special defense mechanisms such as poisons or nocturnal behavior. Therefore birds are relatively easy to watch, and can be very beautiful. We saw many, despite none of us really claiming to be bird-watchers. |

| Image courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015 The only thing preventing the Chestnut-eared Araçari being a handsdown favorite was that we saw saw so few of them. | |

I’ve always loved the Secretary Bird. It scores high marks for size and color, has a lunatic look about it, and is a snake-eater, killing by stomping on them. What’s not to love? They prove nature has a sense of humor. To this "Mad Hatter" category I am delighted to include the hoatzin, a splendid addition that looks like it came off the drawing board on day one of design school.

The hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin), also known as the stinkbird (and in our canoe also known as the "bush turkey") is notable for having chicks that possess claws on two of their wing digits. The chicks are good swimmers and if the nest is disturbed they drop into the water and swim under the surface to escape, then later use their clawed wings to climb back to the safety of the nest. The alternative name of stinkbird is derived from the bird's "manure-like odour," caused by its unusual digestive system. It has an enlarged crop, used for fermentation of vegetable matter, in a manner broadly analogous to a cow's digestive system. As a result it is only hunted by humans for food in times of dire need. The hoatzin's crop is so large it displaces the flight muscles and keel of the sternum, much to the detriment of their flight capacity. Adults can fly clumsily for short distances, but they spend most of their time perched, digesting their leafy food (again, cow-like). A large rubbery callus on the bird’s breastbone acts as a tripod to keep it from falling over when its stomach is distended. You can't make this stuff up. This is a noisy species, with a variety of hoarse calls, groans, croaks, hisses and grunts. Calls are used to maintain contact between individuals in groups, warn of threats and intruders and by chicks begging for food. |

Image courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015 Image courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015 |

The hoatzin is the only member of the genus Opisthocomus (Ancient Greek: "wearing long hair behind", referring to its large crest), but its taxonomic position has been greatly debated, and is still far from clear. Rumors of the hoatzin being related to the Archaeopteryx appear to be exaggerated, and indeed EvolutionWiki claims that Archaeopteryx was probably the more competent flier. Redmond O'Hanlon had this to say:

| There was a rasping and hissing noise; something began to thrash the leaves above us. And then I saw a hoatzin right above me—it was pheasant-sized, chestnut and orange-white, with spread wings and fanned up tail, moving awkwardly on a branch, tipping back and forth swearing. [...] they peered down at us with their red eyes and blue faces, a crest of spiky feathers standing straight up from their skulls; and then they would hurl themselves away at the next tree, crashing into the leaves and branches without restraint, all feathers spread. Their wings were large but badly assembled; you could see strips of light through their primaries. [...] 'You can't eat them' [Culimacare] said, 'they smell like Chimo's hammock.' |

|

|

|

Other than the hoatzin, the three runners-up prizes went to the chaps above: parrots, toucans, and of course the macaws. Due to the light and the distance, they were all hard to photograph; often the best sightings were of them in flight. A trio of toucans flapped overhead. Edi didn't turn around, he just pointed to the sky in his customary style and said more-or-less to himself "threecans." Arf. Redmond O'Hanlon again:

| [On Channel-billed toucans] they decided, one by one, that we were not to be trusted: a jump off the frond, a few quick flaps, and they were seemingly towed down and across the river by their bills, missiles following their nose-cones, each bird entering the foliage on the opposite bank in a low, mad glide. |

8am: Breakfast

I can’t say we’d actually earned breakfast, having just sat on our derrières all morning, but we were certainly ready for it, and it did not disappoint. Fresh fruit, sliced deli meats, some sort of egg dish, sausages, and a freshly baked cake (every day something a little different). The trouble was the usual buffet trouble: even if one can resist the strong urge to clear the buffet, one cannot resist the urge to try at least a little of everything, resulting in a large plateful of food every time.

Before we can eat, Edi has to explain the manioc thing. “This,” he says, lifting up a spoonful of yellow granules from what I’d assumed until that moment was a sugar bowl “is manioc. It isn’t a meal if it doesn’t have manioc on it.” He sprinkled the spoonful over the rest of the food on his plate. Out of respect many of us dutifully do the same, or at least make a little pile of it on the edge of the plate. Souza picks up the story: “Once in the early days, when Mark Baker [the proprietor] was on the boat, we ran out of manioc. ‘No problem’ he said, ‘We can get some more when we return to town in a couple of days.’ We said to Mark ‘we don’t think you understand. Without manioc we cannot eat. And if we cannot eat, we cannot work.’ Mark sent a canoe out to the next settlement we came to, and bought enough manioc to last the trip. We’ve never run out of manioc since.”

10am: Jungle Walk

Image courtesy and © Lucy Mueller 2015 |

Jungle-walking required a full suiting-up: hats, long sleeves, long pants, boots, gaiters. This was not just protection from the animals, flying or otherwise. One day Edi was poking around looking for nuts in the debris from a fallen tree with spines like a sea urchin and he gently backed into one of the fallen limbs. A spine slipped straight through his rubber boots and stabbed his foot. To get to terra firme, the canoes often had to travel some distance from the boat, and as we got out into open water, the pilot opened up the throttle, or “turned on the AC” as Souza liked to call it. If the bumpers were out this could cause some splashing, and Lucy heard the pilot call out to Edi at the front (in Portuguese of course) “the Americans are getting wet!” Edi immediately turned and called for the bumpers to be pulled inboard, but the damage was done. Whenever we were getting splashed we would call out from the back “the Americans are getting wet!” and the bumpers would be adjusted. As we approached the far edge of one of these full-speed open water stretches, Pakito headed straight for a tree top poking out of the water, playing chicken with Edi by not turning to avoid it until Edi starting frantic arm-waving signals. |

Image courtesy and © Lucy Mueller 2015 |

Eventually we would find what we were looking for, but not until we’d been through a maze of channels and not-channels where we had to maneuver around the all-but submerged trees and bushes, some of which scraped along the bottom, requiring a surge of power as we got close and then lifting the prop out of the water as we slid over.

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015 |

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015 |

How we found our way in and out again is a mystery. It was certainly as challenging as it looked, the pilot and the guide often discussing which way to turn next. But we were definitely looking for a specific spot, because when the canoe finally nosed up onto the bank, there was always a path to follow from there.

It was really hard to find things. This came as a bit of a surprise. With all that life and diversity, one imagines that one would be fighting things off with a stick (figuratively if not literally) but of course nothing wants to be seen, either because it doesn’t want to be someone else's lunch, or because it doesn’t want any potential lunch to know it is there. The monkeys were different: smart enough to be curious, they were always in the farthest trees, maximizing the distance between us, but allowing them to keep an eye on us. This made it possible for us to see them too, but generally with great difficulty. I was always glad to have Pakito, the backup guide and canoe pilot, along with us because he seemed to be an expert at finding monkeys. After apparently overstaying our welcome, one group started throwing sticks and dung. We got the message. So the only rule we had was “step over logs, not on them: you never know what is hiding in or on the log. Also, it may not be a log.” But other than that, we never felt in any sort of danger, and would step off the trail to get a close up photo of something, or to let someone by. On the other hand we never touched anything, and once Edi was only one stride from stepping face-first into a golden silk spider that had built a web right across the path. |

|

A column of army ants marched right across the path and on up a small tree. More impressive, Edi found a colony of bullet ants at the bottom of a tree trunk, which he mustered by banging on the trunk with the back of his machete, causing the inch-long ants to pour out of their burrow to defend the tree. Also known as the “24-hour ant” it has one of the most painful stings in the world, said to be equal to being shot, and continuing unabated for 24 hours, hence its names. Pause here for a moment to consider the life-style of a person who has qualified to make this comparison by being both shot by a bullet and bitten by a bullet ant. Naturally, one of the native Indian tribes, the Satere-Mawe, use intentional bullet ant stings as part of their initiation rites to become a warrior.

|

Image courtesy and © Richard Thomson 2015 |

Far left: Jungle! A relatively thin section, allowing the sun to shine through the canopy.

Left: 5ft lily pads. Research suggests that they can get much bigger, and that tourists have been known to sit on them. Some sort of kitchy pixie photo op I suppose.

Right: We came across a tree that looked like it had been used as a scratching post. It had. Someone asked about the likelihood of our meeting the owner of the claws. Souza: “It’s probably better we do not meet Jaguar and other creatures that can make you weak.” Amen to that. |

Image courtesy and © Brian Gourlie 2015 |

One day Edi found another hole at the bottom of a tree trunk. He cut himself a twig about 18 inches long with a leaf on the end of it. He cut the end of the leaf off, creating a sort of long-handled shovel. “Get your cameras ready, I’m only going to do this once.” He poked the shovel into the hole until it clearly met some resistance, and then gently pulled it out again, dragging with it a spider about 5 or 6 inches across. Not one of those itty-bitty all-legs variety, a big fat more-like-a-soft-shell-crab one. Everyone stepped back a little, and would have kissed their gaiters if they could have reached them.

Image courtesy and © Brian Gourlie 2015 | “Bird-eating tarantula.” The tarantula (the biggest, by mass, in the world) waved its pedipalps and front legs as menacingly as it could, which was pretty effective in my view, and after a brief circuit to check out the immediate surroundings (everyone took another step back) scuttled back into its hole. Best of show. Hands down. I got it on video: see for yourself. Right: Even with a spot-light on it, and knowing that it is there, it is crazy how hard it is to make out the spider. Note Edi's shovel. In a perfect demonstration of how desperate for food the local tribes can get in this apparent abundance, the spider is part of the local cuisine in northeastern South America, prepared by singeing off the urticating hairs and roasting it in banana leaves. The flavor has been described as "shrimplike", and I bet it has the texture of a soft-shell crab. I haven't tried it because I absolutely do not like it. |

|

|

Souza showed us some leaves natives use to make ayahuasca tea (aka yagé aka the vision vine, aka the vine of the soul). This hallucinogenic brew was first described academically in the early 1950s by Harvard ethnobotanist Dr. Richard Evans Schultes, a larger than life character about whom there was a book in the Tucano’s library. He seems to have been Harvard’s Hunter S. Thompson, an expert in, and seeker out of hallucinogenic plants. (See also Dr Schultes's own rathole on the ecology page.) People who have consumed ayahuasca report having spiritual revelations regarding their purpose on earth, the true nature of the universe as well as deep insight into how to be the best person they possibly can. This is viewed by many as a spiritual awakening and what is often described as a rebirth. Sounds like good stuff, but wait, there’s more: vomiting can follow ayahuasca ingestion as well as significant, but temporary, emotional and psychological distress (the "bad trip" experience). This purging is considered by many shamans and experienced users of ayahuasca to be an essential part of the experience, as it represents the release of negative energy and emotions built up over the course of one's life. |

"Ayahuasca and chacruna cocinando" by Awkipuma - Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons |

Obviously this was the sweatiest part of the day: the sun was high, and we actually had to exercise. Speaking of exercise, onboard Fitbits were going bonkers: some appeared to be counting something the boat was doing, and their owners were apparently running marathons every day, others, more accurately were panicking because their owners were only walking 10% of their normal values. The thousand steps this left them doing were all performed out here in the jungle in the midday sun. Imagine the delight then, as we climbed back into the canoes, when from the back the pilot starts passing frozen washcloths forward from a cooler he'd secreted aboard. This is probably the first and only time in my life when I was not disappointed that the cooler contents turned out not to be beer.

Back on the Tucano, this was the time to shower. As with most boats, the floor/deck was cambered for drainage, so rightly, the shower drain was on the outside/downhill side of the shower. But the Captain was generally in such a hurry to get going that once when we were running a few minutes behind he actually up-anchored and motored towards the errant canoe and we had to rejoin the Tucano "on the hoof." Therefore almost always we were underway before we could strip for the shower. The result was that our starboard cabin was sometimes listing to port so hard that showering was a two-person operation, one person showering, the other using a foot to bail water back towards the drain. The shower water was the same tea color as the river (because it was the same water), which was not a problem, but was a bit alarming as I was rinsing out my smalls when I first noticed it. Then, luxury, changing into fresh(er) or at least drier clothes. Even dry was a term to be used loosely. Nothing is ever actually dry in the tropics. Only a little damp is the best you can do.

1pm: Lunch

I never get tired of rice and beans, and fortunately we had it several times. The most curious addition was chopped up hot dogs in some sort of bbq sauce but what's not to like about that? We had fish more than once during lunch as well as chicken and beef pieces. I was not surprised that the beef was my least favorite dish, (when in a fish region eat fish). Later on our visit to the Manaus market we discovered fish was more expensive than meat even 500 road-free miles from the nearest cow. Strange, and so much for not being practiced at cooking beef. There was also salad and fresh fruit of course, and fruit juices which I learned to be careful with after a frozen lump cascaded out of the jug and totally overflowed my glass, my hand, and the tablecloth.

2pm: Siesta? Or not

FOMO. Fear Of Missing Out. While the majority did the sensible thing and took a well-earned nap, a few hardy souls were to be seen lounging on the observation deck, binoculars in hand. The guides had predicted this: on the first day most people were hanging around, but they said this soon wore off and after a day or two the crowds thinned out considerably. But who knows what the snoozers might miss? So we watched the world drift slowly by. There was something very calming about it. And sometimes FOMO was a legitimate concern: there were things to miss. Oropendola (genus Psarocolius), are known (along with the caciques) for their hanging nest colonies, some of which can contain 100 nests hanging from the branches or fronds of a single tree, and these condos were a common sight along the river bank. The colony members select a large tree that is isolated, presumably to reduce the chance that a monkey or other arboreal predator can climb into the colony and raid the nests for eggs and young. Only the female builds the long, windsocklike nest. Inside this woven structure she incubates two white eggs and then feeds the hatchlings. |

|

|

Both sexes are largely black or greenish, but the bill is usually a strikingly contrasting feature, either pale yellow, or red-tipped with a green or black base. In several species there is also a blue or pink bare cheek patch. They are very vocal, producing a wide range of songs and calls, sometimes including mimicry. In short, a bunch of characters and those of us on watch were treated to their flashes of color several times. The river was so full of islands that we were almost always hugging a bank on one side of the boat or the other. We got used to switching sides or positioning one's chair in the middle and just turning all the way around when this happened. |

|

For a change of scene, sometimes we would lean over the bow, watching the orange-tinted wave crests as we cut through the water, sometimes looking out the back at the canoes we were trailing, or the storm chasing us up the river and finally overtaking us. Initially the storms drove us downstairs, but we eventually learned that no matter how permanent the weather looked, after ten minutes it always stopped again, so we just sat through it.

|

Left: In the white band at the top of this cliff you can just make out Ringed Kingfisher nest holes. Some claim they also saw the kingfishers flashing around, but I didn't see one until much later. Right: five minutes before the worst storm. We were about to cross some fairly open water so instead we anchored close to these trees until it passed over. The Tucano had once been caught out in this open stretch of river, and battling six foot waves they'd been forced to cut the canoes free. That wasn't going to happen again. |

|

Best of show for the siesta slot was without a doubt the dolphins. They were a regular sight all along the river, but on a couple of occasions a whole pod was at play all around the boat. They were even more difficult to photograph than the birds because they only broke the surface for a second. A good subject for the video camera, but I never got to it. Eventually we learned to tell the difference between the grey and the pink. The pink is the larger of the two, and snorted loudly when breaching. The flattened dorsal fin is a giveaway, once you are confident enough to know you are looking at a lack-of-feature, as of course is the pink color if enough of the dolphin clears the water.

The grey apparently will clear the water like the bottle-nose, but we never saw this. Rather the distinguishing feature was the more pronounced dorsal fin. One particular display was long enough, close enough and frequent enough that I went down to our cabin and collected Claudia to come up and share the show. Awesome.

As my grandpa used to say "sometimes I sits and thinks, but mostly I just sits." The skies were the best part.

4pm Afternoon Canoe/Kayak

As we suited up for the third excursion of the day Lucy quipped "I feel like I'm in a play with these constant wardrobe changes."

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015 |

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015 |

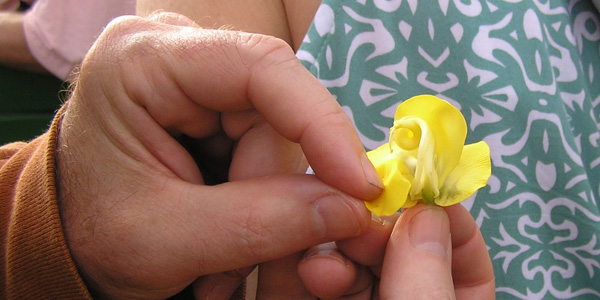

You will have spotted by now that I'm not much of a plant guy. But there were some exceptions to this. Two of them occured at the same stop.

We were at the far north of the trip, and about to turn the Tucano around and head south again. We had come out in the canoes to the Rio Branco. Souza had called a halt because he wanted to show us the cana-rana (false cane) plant. Famous for its efficiency at clogging up waterways, the reason it was important to us was that it only grows in water with reasonably high levels of nutrients—which black water rivers like the Rio Negro do not supply.

|

|

Image courtesy and © Lucy Mueller 2015 |

So this was proof that we were for a brief moment floating on white water, and a glance over the side confirmed this: the water had taken on a decidely soupier appearance. Now that he'd mentioned it, there were also more bugs. Not a big problem, but definitely more than the "none" that we were used to. Ever imaginative with names, Branco is Portuguese for "White" making a nice pairing to the Black River on which we were spending most of our time. While we were sitting there, Souza spotted a best of show flower. We are still trying to track down what it actually was, but it's pollination mechanism had to be seen to be believed. He had to wobble his way around both canoes showing a couple of folks at a time, and I still had to bring it back tp the Tucano so I could make sure I had captured it properly on video. A bee lands on the petal I'm holding, and its weight causes the stamen to be levered out of its tube so that it can deposit pollen on the back of the bee's neck. Really, you can't make this stuff up: you have to see for yourself. |

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015

Next in the notable flora section was the tauari, one of the tallest trees in the canopy, with striking pink blossoms. In the tree tops (above), humming birds could be seen servicing the flowers, while down in the channels (below) the blossoms carpeting the water surface like confetti at a wedding made for some of my favorite photo ops in the entire trip.

Image courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015

The last thing in the flora category for some reason didn't catch my attention much during the trip, but as I look back I'm haunted by the image of the long roots hung from the canopy in so many trees. They were utterly straight and consistent in width—exactly like thin ropes—it was like being backstage at the theatre. Sometimes as with these shots from Mary, they were in trees along the bank of the river, but just as often we were brushing them aside in the canoes as we pushed through the undergrowth.

I’m pretty confident that they are roots from an epiphyte (plants that grow harmlessly on another plant—typically a tree), because they came so directly from the canopy, and were routinely so far away from the tree trunk (so not, for example the early stages of a fig strangling). Mary's shots clearly imply that their owners are the elephant ears growing in the tree tops. Interweb descriptions of elephant ears mention that there are 3000 different species but don't mention any of them generating 100 foot long roots. Another popular tree top epiphyte are the bromeliads but there are more than 3000 of those too, and still no mention of any prowess in dropping roots.

Swimming

Fresh-water swimming beats hands down the chlorine bath of public swimming pools or the stickiness of salt-water. Fresh water is clean, invigorating, and just generally leaves one with a feeling of, well, freshness. Nevertheless there was only one canoe’s worth of folks ready to try it, and Adam was not in the canoe. RT: “This is not right. In his whole life he’s never turned down an opportunity. I guarantee he’s coming.” “Just like his father” Claudia muttered. Spectators remaining on the Tucano called up to him and almost simultaneously he came bounding down the stairs, grabbed the life jacket thrust into his hands as he rushed past, and jumped in the canoe as it pulled away.

We puttered to a spot about 100 yards from the Tucano. Edi threw a life buoy over the side, carefully following it himself like a scuba diver protecting his gear. Everyone followed suit, except Adam, still not wearing his life jacket, who naturally did a backwards flip off the canoe instead. At first the life jackets felt like over-caution, and they definitely hampered swimming, but this soon gave way to the pleasure of just being able to relax and float.

Image courtesy and © Brian Gourlie 2015 |

Image courtesy and © Adam Thomson 2015 |

Even in this meticulously chosen spot, there was a noticeable current, and one had to kick idly to maintain position. But it was bliss, the water was a perfect temperature, my clothes were getting washed, and in some ways the tranquility was the pinnacle of our whole peaceful, away-from-it-all-especially-electronics, journey.

Nobody wanted to touch the bottom even if we could, (who knows what would be lurking there) and as Kevin pointed out, for once nobody wanted to pee either. Most of us had read accounts of the candiru about which even my reference guide waxes lyrically:

| These needle-shaped catfish are adapted to dwell in the gills of large catfish, where they extract mucus and blood. [...] According to native folklore, these fish are also attracted to urine, and they are reputed to enter the penis of a man who is urinating by the side of a river, by swimming up the urine stream. These reports are no doubt apocryphal. Candiru do, on occasion however, enter the urethra of both male and female bathers, perhaps attracted to their urine. However remote the likelihood of this unpleasant event, the mere prospect is sufficient to cause most would-be underwater micturaters to think twice, even the most skeptical. |

Nuts! (Brazil)

|

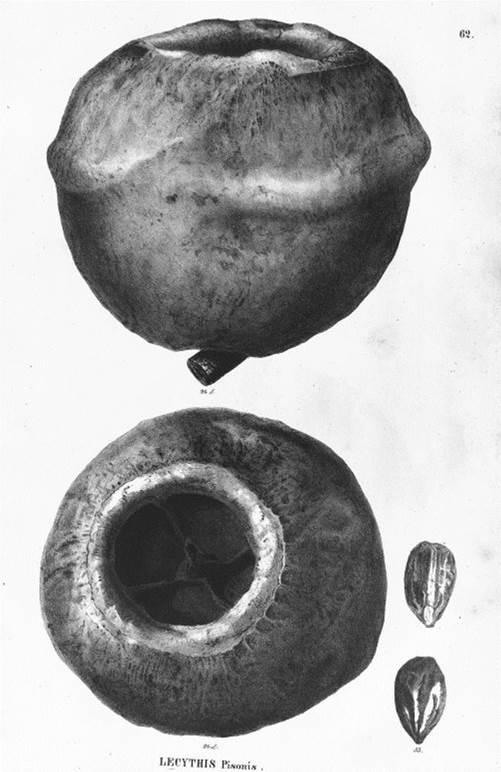

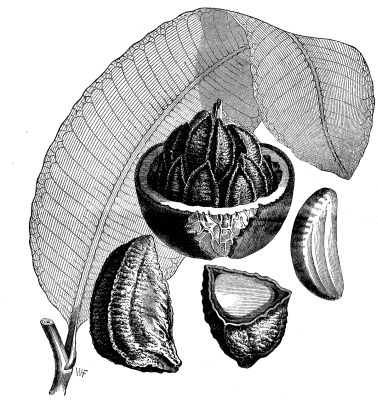

Another botanical specimen and story that captured my imagination was this one, concerning two different trees in the Brazil nut family. Sapucaia (lecythis pisonis) aka monkey pot grows to a height of about 30 metres (100 ft). The fruit is shaped like a cooking pot and contains edible seeds. The nuts are eaten by animals and the name "monkey pot" comes from the old proverb "a wise old monkey doesn't stick its hand into a pot" referring to the fact that a young monkey may plunge its hand into the container and not be able to withdraw the fistful of nuts whereas an experienced individual will remove the nuts singly. The (empty) monkey pots were a common feature on the forest floor. The Brazil nut tree itself is a much larger tree, reaching 50 m (160 ft) tall, making it among the largest of trees in the Amazon rainforests. It may live for 500 years or more, and according to some authorities often reaches an age of 1,000 years. In Brazil, it is illegal to cut down a Brazil nut tree. As a result, they can be found outside production areas, in the backyards of homes and near roads and streets. The 2kg (5lb) fruit capsule poses a serious threat to vehicles and people passing under the tree. At least one person has died after being hit on the head by a falling fruit. As the Brazil nut is a botanical seed, and unlike botanical nuts, the density of the fruit makes them sink in fresh water, which can cause clogging of waterways. |

|

The hard, woody shell contains eight to 24 triangular seeds 4–5 cm (1.5–2.0 in) long (the "Brazil nuts") packed like the segments of an orange. The capsule contains a small hole at one end, which enables large rodents like the agouti to gnaw it open. They then eat some of the seeds inside while burying others for later use; some of these are able to germinate into new Brazil nut trees. Most of the seeds are "planted" by the agoutis in shady places, and the young saplings may have to wait years, in a state of dormancy, for a tree to fall and sunlight to reach it, when it starts growing again. Capuchin monkeys have been reported to open Brazil nuts using a stone as an anvil.

And so finally to the story: the Brazil nut tree is a huge tree with comparatively small fruit. Its cousin the sapucaia is much smaller, but with a much larger fruit. God made the Brazil nut for man as the only animal (except the agouti) with the tools necessary to crack into the fruit to get at the seeds (and you know how hard those are to open), and he made the sapucaia for everybody else.

| Rathole: What's the difference between a seed and a nut? |

A seed is defined as the part of a flowering plant that contains the embryo and will develop into a new plant if sown. Since this applies to both nuts and seeds, it stands to reason that all nuts are seeds but not all seeds are nuts. In common parlance, a seed comes from a (generally fleshy) fruit and can be separated: apples, tomatoes, raspberries. With nuts, by contrast, seed and fruit cannot be separated, they are dry, generally one-seed-at-a-time, consisting of a kernel, often edible, in a hard and woody or tough and leathery shell: chestnuts, acorns, hazel, are nuts and this is why things like peanuts are assumed to be nuts (they are legumes, along with regular peas and beans). The Brazil nut has a very tough fruit (called a capsule), but once inside, indeed the multiple seeds are easy to separate out. These seeds are what we buy as Brazil nuts. Where things get really interesting, and confusing, is with the introduction of drupes. A drupe is a fruit that is pulpy on the outside, and has a hard shell on the inside that contains one seed (so drupes have fleshy fruit like seeds, but a singular seed like nuts). In most cases the outer fleshy part of the fruit is eaten and the “stone” is discarded. Examples of this are plum, peach, cherry, olive, where you would never imagine eating anything but the flesh. However, in some cases the seed within the fruit, is actually the part usually eaten whereupon we call them “nuts." It turns out that many of the things we assume to be nuts are actually drupes. Famous examples of drupes where we eat the seed not the fruit: almonds, walnuts, coffee, coconut, pistachio. And just when I was ready to say, okay if a seed or drupe stone is edible, then we call the seed a nut, I remembered mustard, poppy, and sesame. If you are still confused, I don’t blame you. I wrote this sidebar from scratch twice in an effort to straighten it out. I see where they are going with it, but if I were given a random “seed” and asked to determine from the rules if the sample belonged to any of these special categories, I would be totally incapable of doing so. A simple rule of “most nuts are not” would seem a good one. The Wikipedia page on nuts has a far most extensive list of things that are not nuts than it does of examples of “true” nuts. Lastly, this led me to one last question: what’s the evolutionary advantage of making the seed/nut, (the actual “embryo" remember) edible—isn’t that counter-productive? It seems that the animals (mostly rodents and birds) that eat these nuts do a much better job of dispersing (and even sowing!) the nuts than older mechanisms such as wind could ever do. It’s okay for the dispersers to eat most of the nuts, provided they don’t eat all of them. |

|

Iguanas do an excellent job of blending with the trees that they live in. The only reason we were ever able to spot them was when a branch seemed to bulge in the middle like a snake that has swallowed a rat. It was amusing to listen. Some folks found it really hard to find them, but once one had, it was ridiculous how easy they were to see. |

|

Fishing

The piranha fishing expedition was much more popular than the swimming. Both canoes set off, and hacked their way into spots where there was enough room to put out the lines in a secluded canopy of trees. One fisherman remarked that “this goes against everything I’ve ever learned about fishing.” But piranha are not regular fish. Edi and Souza gave us a long lecture before departing, stressing the importance that under absolutely no circumstances whatsoever were we to make any attempt to touch or otherwise interact with the fish. Once it was on the hook, they would handle everything.

The rod was a simple bamboo pole, six or seven feet long. The line was an inch shorter than that, so that the equipment could be stored and transported safely simply by pulling the line tight and inserting the hook into the handle end of the pole. Souza handed out a plastic cup to each of us. It was full of shredded beef. We packed enough beef on the hook to hide it completely.

Image courtesy and © Domenica Puleo 2015 Image courtesy and © Domenica Puleo 2015 |

Holding the hook and bait firmly in one hand to put tension on the pole, we whipped and thrashed the surface of the water for about 5 seconds, and then dropped the line into the center of the disturbance. Apparently in the other canoe when Edi demonstrated this he had no sooner dropped the line when he pulled it back out again with a piranha dangling on the end. The thrashing water mimics something in distress, and the piranha come over to put it out of its misery. They were clinical about it. Time after time I pulled the line out of the water to find the hook picked clean without me feeling a thing. When we did catch something, of course the first thing to do was get your picture taken, then gingerly swing the catch over to the end of the canoe for a guide or pilot to unhook it. Everyone in between had a brief moment of panic as it came by, dreading the possibility that it might drop off into their lap. Not only do they have teeth, they also have nasty spines, and so getting hold of one is a very careful process. Once securely gripped and dehooked, Souza says “this is why we don’t want you to touch them” and shoved a twig between its teeth. There was an audible snap, like pliers cutting wire, as the piranha dutifully bit clean through the twig. “Same with your finger” says Souza to the stunned crowd. “Do it again! Do it again!” we all cried like a bunch of first-graders. What a show. |

|

I think for most of us piranhas are right up there with spiders and snakes as things on our primal fear list, and yet here we were, vulnerable in our canoe, and looking them right in the eye. Or in my case at least, right in the teeth. I think that there was something so visceral about the experience that we reverted: in a way we were first-graders again. If I were a guide, I would never get tired of watching guests go through this somewhat humbling process. In summary: piranha are not hard to catch, but not easy either, and we tried several different holes before Souza decided we had enough for appetizers and we headed for home, an outing few of us will ever forget.

5-ish: Appetizers on the observation deck

Appetizers ranged from feta cheese and olives to freshly fried plantain chips. A highlight, of course, was eating the piranha we had caught the previous evening.

Fresh-fried piranha. Image courtesy and © Brian Gourlie 2015 |

|

Fresh-chewed piranha. Image courtesy and © Brian Gourlie 2015 |

Late in the trip, Souza demonstrated how to make caipirinhas. I'm sure on the average trip the whole experience was a surprise, but of course we were way ahead of him, and days earlier had even had him make us a round of them with our own cachaça. Nevertheless his instruction, demo, and our subsequent practice were an absolute blast.

|

|

On the last evening we fetched in a guitarist (above left, all the way to the back, and below, in the bow) who plucked Brazilian favorites while we made caipirinhas from the cachaça and limes that miraculously appeared where the appetizers were normally parked (yours truly front right, followed by Lucy, Virginia and Domenica on the left already enjoying theirs, and Edi adjusting the party lights in the middle distance). |

|

|

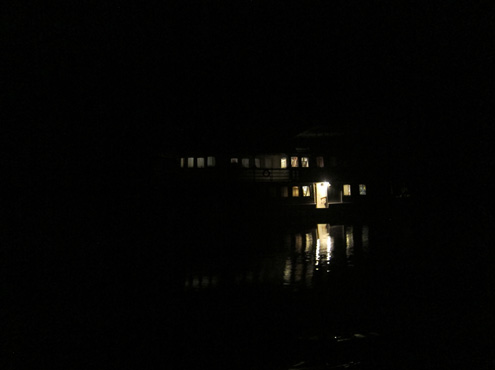

This was a splendid prelude to a fabulous celebratory feast being laid out in the salon, and also a brilliant move on our host's part, as it for once distracted us from staring at the view, which for the most part was comprised of the less attractive side of Manaus as we made our way back for our final night-stop anchored just off-shore from Hotel Tropical. |

RT, BG guilty as charged. Image courtesy and © Domenica Puleo 2015 |

Rathole: cachaça Although both rum and cachaça are made from sugarcane-derived products, in cachaça the alcohol results from the fermentation of fresh sugarcane juice that is afterwards distilled, while rum is usually made from by-products from refineries, such as molasses. They have distinctly different flavors, with the cachaça reminding me very much of the hooch (akpeteshie) that we drank in Ghana. A caipirinha is prepared by mashing a quartered half lime and sugar together, and adding the liquor. A recipe I looked up went on "This can be made into a single glass, usually large, that can be shared amongst people, or into a larger jar, from where it is served in individual glasses." We made them in large glasses, and then did not share them. It seemed a reasonable compromise. More recent experiments and research suggest that key limes might be a better choice than our regular ones, which in my opinion give the caipirinha a bitterness that I did not notice in the originals. |

|

The fetching of the guitarist is a story in itself, Adam and I mentioning it independently as one of our favorite moments. I'd been talking to Souza about sourcing some cachaça like the bottle he had served the previous evening. Firstly we'd drained our supply, secondly we wanted to take some home, and thirdly, we figured he was not spending $50 a bottle. He invited me to join him when he went to collect the guitarist, and we'd go find some. Ab-so-lutely! When Adam announced he could use some cash, Souza was happy to take us both. As soon as we returned from the afternoon canoe trip, Adam and I hung back in the canoe, Pakito jumped in, and the four of us set off. First win: the trip took us right across the Amazon river, and so took a good 15 minutes even with the "AC turned on full-blast" and for the first time the canoe crashed up and down a little on the waves of the open water. Second win: we plowed our way right into the heart of the Port of Manaus, and finally pulled up at a dingy quay so narrow only small vessels like ours could have squeezed in. The guitarist was waiting for us and helped pull us up onto the dock itself, which was chest-height from the canoe. The usual rotting smell of garbage and fuel didn't stop the inevitable street vendor plying a trickle of customers for his snacks and drinks. Old pallets formed a dry path across the standing pools of black water, and then we were on a street full of small shops leading up and away from the river. |

Rathole: Curare Curare is a collective name for various plant extract poisons that cause weakness of the skeletal muscles and, when administered in a sufficient dose, eventual death by asphyxiation due to paralysis of the diaphragm. An effective curare can be made simply by boiling down several kilos of any combination of 20 different species of jungle leaves. Once it becomes a thick syrupy tar it will most likely be able to bring down anything from a monkey to a man. In addition, it is said, the final preparation is often made more potent by adding irritating herbs, stinging insects, poisonous worms, and various parts of amphibians and reptiles to the preparation. Some of these accelerate the onset of action or increase the toxicity; others prevent the wound from healing or blood from coagulating. So what, then, was Edi offering us when he invited us to try eating “curare” berries (“delicious, but don’t bite into the seed”)? One possible answer is Strychnos toxifera, a known ingredient which at least has a fruit, and which is also in the family that produces strychnine, which some folks claim they also heard mentioned. Some of us took up the challenge to try it. It really was quite good—kumquat-like, but more delicate. |

About 75 yards up the street Souza disappeared into a convenience store, and showed us the ATM by using it first. There was the usual heart-stopping moment when Adam's credit card disappeared into the bowels of the machine but it didn't want to hand out any cash in return. After a couple of false starts, it finally played fair and proffered up both cash and card. I noticed that the store had the exact same cachaça bottle as Souza had provided. $8. I kid you not. Souza shook his head "no." Heading back towards the port we popped into a second store, even smaller than the first. Same bottle. $7. Souza bought one, we bought all the rest. We also splashed out on a deluxe bottle ($9) and a six-pack of beer for the journey home. Feeling very chuffed with ourselves, but smarting more than a little over the $50+ prices we'd paid at the cachaçaria for our first batch, we headed back to the canoe. The musician refused a beer (just coming on duty), Pakito refused a beer (getting over a cold) and Souza refused a beer (not before dinner thank you). No such compunctions for us, Adam and I pulled the rings on ours, and before we could get the cans to our lips, the Tucano came into view. Since we were going to be following the northern bank of the river back to the Hotel Tropical, the captain had used the time to also cross the river. Everyone seemed to have turned out to watch us return, and were able to witness the sight of Adam and I frantically guzzling beer trying to finish before we caught up with the boat. |

|

6pm: Dinner in the salon

There was a sameness to the ingredients of each meal that buffets seem to encourage, and there were also distinctions. Deli meats and sliced cheese were only served at breakfast, and ice-cream only at dinner. Rice and beans would never be served at breakfast, but different sorts of cake definitely were a breakfast thing. And despite this, there always seemed to be a more relaxed atmosphere at dinner (not that it was ever not relaxed) just a sort of "ah, another great day to savor" sort of thing.

|

"There are three ways to get tambaqui: by line, by spear, and by supermarket.” |

|

Exotic dishes like the tambaqui would usually appear at dinner time (quite right). Tucunare (peacock bass) was another exotic and delicious fish, but for some reason it was always served "fish finger" style so there was nothing photogenic about it. Even the boozers amongst us tended to restrict consumption to dinner, or even beyond, especially if there was a night trip. So after the tambaqui, the most exciting part of dinner was “what flavor is the ice-cream tonight?” It was always different, and even better always something no-one had ever heard of:

|

|

8pm: Night trip in the canoes

I lurved the night trips. If we were going to see something, it was bound to be something dangerous—who else is out at night? Safety in numbers, safety in the canoe, and most of all safety in the hands of experts. Bring it on. It was a little creepy at times I have to admit, but we were not disappointed. Here I've tried to recreate the experience. At left is a typical scene. Having spotted that something unusual is up the branches, (many of us would have seen nothing at this point—there is some zooming here already—the guide turned off his spot lamp while we drifted under the low-hanging canopy in the pitch dark. Eventually he turned it back on. Roll your mouse over the image to see what was then revealed. A six-to-eight foot long tree boa. Check out the knot at the end of the tail securing him/her to the branch. We spent a considerable amount of time chasing red reflectors. We would see an eyeball further up the channel and then home in on it. For reasons I never figured out, the eyeball rarely disappeared until we were right on it, and even the birds could not be disturbed. One small spectacled caiman even allowed itself to be caught. Apparently we were very unlikely to see anything much bigger than that. Firstly because statistically the little guys vastly outnumber the big adults, and secondly because the adults are typically deeper into the undergrowth. |

Image courtesy and © Lucy Mueller 2015 |

Image courtesy and © Mary Clements 2015 |

10pm: Good lord, is that the time?

Virginia complained that she was normally a night owl, but "I can't keep my eyes open." This was a very quiet time. It was several days before we discovered a light switch on the observation deck, and even then more often than not it was not used. Most of us agreed with Virginia, and retired to the land of nod. A few night owls hung about, reading or chatting over a nightcap. I managed to stay up at least once, and it was certainly delightful, tranquil, cool, but the thought of the 5:20 alarm call prevented me from lingering long.