| Preface | Perth | Stuart Highway | Uluru | Port Douglas | Sydney | Sturt Highway | Kangaroo Island | Indian Pacific | Perth |

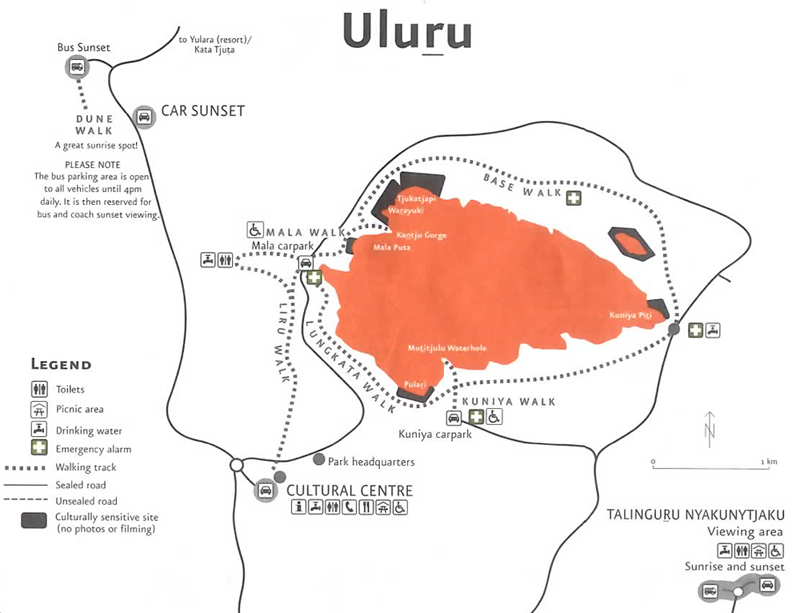

Uluru / Kata Tjuta National Park.

Without question, for me Uluru was one of the most eagerly anticipated stops for the trip. Another of those decades old bucket list items, its remoteness also made it one of the least likely to be achieved. But here we were. Although the weather pushed our luck—cloud cover would not have been good for the spectacular color display, especially at sunup and sundown, which we'd very carefully planned to enjoy—in the end all was everything I could have wished for, and more. We walked all around the base at dawn, we had a delicious al fresco dinner at sunset, and in between we even had time to see Kata Tjuta, Uluru's alter ego.

Because of it's importance, I went to enormous trouble to document every step along the way, even carrying a voice recorder so I could tape the words of wisdom our guide had to offer. But a combination of setting off in the dark, many of the signs seeming to be identical and then they were not, and the many areas we were not allowed to photograph, I ended up being hopelessly confused. After spending too many hours trying to untangle it all, and with the months blurring and jumbling the memories still further, I have given up, because in the end, what does it matter? So this section is the usual mixture of my notes, material I've stolen from the interweb, and edited transcripts of the stories told by our excellent guide Francesca. In no particular order.

Uluru is part of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park which is sacred to the Anangu people, who have lived here for more than 30,000 years. Uluru is estimated to be around 600 million years old, stands 348 m (1,142 ft) high, with a total circumference of 9.4 km (5.8 mi). The vibrant orange-red hue of Uluru is due to surface oxidation of its iron content. From sunrise to sunset, the colors change as different aspects of the rock illuminate.

The "no photography" rules we came across all over the place as we circumnatigated Uluru also applied to the whole thing. The reason all photos of Uluru look the same is because they all have to be taken from this one spot.

The "no photography" rules we came across all over the place as we circumnatigated Uluru also applied to the whole thing. The reason all photos of Uluru look the same is because they all have to be taken from this one spot.While Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park might look arid, it is still abundant with native flora including bush plums, desert raisins, native figs, she-oak, honey grevilleas and wildflowers which carpet the red earth in purple, orange, pink and white after the rain. There are also 21 species of mammals, 73 reptiles, 178 birds and four species of frogs in the park.

The Aboriginal traditional owners of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park call themselves Anangu (pronounced arn-ahng-oo). The Anangu people traditionally hunted these animals and collected this ‘bush tucker’ – also including such things as honey ants and witchety grubs. By contrast, we saw 0 mammals, 1 reptile, 3 or 4 birds and 0 frogs.

The aborigines may not have had pencils or clocks, but their oral traditions, passed down from grandparent to grandchild, provide enough detail for a nomad to navigate a crossing of the entire continent. You are raised by your grandparents because your parents are too busy hunting and gathering. One of your jobs as a child is to look after your great-grandparents (if living). They think of you (and refer to you) as a parent, and you think of them as your children. Therefore there is no word for great-grandparent. There is no need: it's a cycle, not a lineage. And the cycle continues in perpetuity. Grandparents teach the stories, and the stories contain the collective wisdom of the tribe. What you can eat, where you can find it, how to behave. There is no word for "why" (a mother of a 2 and a 4 year old sighed wistfully when we heard that). There's no need for "why". It is what it is, it always has been, it always will be, we do it this way or we die. It is the mantra of a subsistance way of life, and as Jerard Steel so eloquently argued in Guns, Germs, and Steel, there's nothing backward or unsophisticated about the people or the way of life, its just that there is no room, no time, to make progress technologically, when mere survival is such an all-consuming business.

Tjukurpa

The Anangu people have looked after, and in turn been looked after by, the land for over one thousand generations. While visually and geologically extraordinary, the physical features of Uluru hold a deeper meaning for its traditional owners. For the Anangu the land carries Tjukurpa, The Law, the knowledge which guides relationships, values and behaviour – and records the journeys of their ancestral beings. Indeed the landscape was actually created at the beginning of time by these ancestors.

Tjukurpa encompasses religion, law and moral systems, it defines the relationship between people, plants, animals and the physical features of the land. Tjukurpa contains the knowledge of how these relationships came to be, what they mean and how they must be maintained.

No surprise then that at the core of Tjukurpa is a deep respect for the land. Anangu believe that if they look after the land, it will look after them. They have an intimate cultural knowledge of the environment in which they live and their traditions and practices connected to the landscape are guided by Tjurkpa. These teachings are passed down from generation to generation through stories, songs and inma (ceremony).

Uluru Base Walk: Kuniya Piti

As best as I can tell, Kuniya Piti is where we started the Base Walk. It also makes sense that we stopped at Mala car park for breakfast, which is on the exact opposite side—half way around. We definitely started on a section where photographs were not allowed, as the map indicates. Right on cue, the sky started to brighten the moment we set off, gradually illuminating Uluru's walls which seemed to rise straight up out of the desert floor. The first thing you notice is the different textures on its ancient sides, from smooth to sandpaper, from cracks to craters. White spots in and on the rocks are often just bird droppings, but the longer stripes are calcium deposits in the rock.

Taputji

Francesca: "You see it is the face of a man. There's the chin and the mouth, and in the back you have got the hair tied up in a bun. And that's actually pretty much what a man would have looked like, with these dreadlocks in the back, and this big one, and they would use it to store things in there."

Francesca: "You see it is the face of a man. There's the chin and the mouth, and in the back you have got the hair tied up in a bun. And that's actually pretty much what a man would have looked like, with these dreadlocks in the back, and this big one, and they would use it to store things in there."Out of the gate was a long sacred section, meaning no photography. No great loss with this little light, but the camera is my memory and therefore sadly, I have few memories. I do remember Claudia trailing behind, which concerned me greatly because I didn't want her to be holding up the whole group, and she was not exactly the life and soul of the partly at this hour of the morning, but her excuse was that she was just enjoying the solitude and the silence, which of course would have been more challenging in the group. But it left me distracted.

Tjukatjapi

Tjukatjapi is an Anangu women's site and sacred under Tjukurpa. Like all the women's sites it would seem, the rock details and features are equivalent to a sacred sculpture; they describe culturally important information and must be viewed in their original location. "It is inappropriate for images of this site to be viewed elsewhere" in other words: no photography. Particular senior women are responsible for these stories which are passed down from grandmother to granddaughter. In an oral culture, stories are family inheritance. As discussed earlier, this is Tjukurpa, cultural knowledge that is earned, and with it comes great cultural responsibility.

Warayuki

Water (kapi) is life. The black stain on the rock is algae growing on the path left by the water spilling over the waterfall that forms after every storm. Note the unidentified little black and white bird perched at the top of a tree.

Water (kapi) is life. The black stain on the rock is algae growing on the path left by the water spilling over the waterfall that forms after every storm. Note the unidentified little black and white bird perched at the top of a tree.

Kulpi Minymaku

The kitchen cave. Women, girls, and small children would camp here. The women would go out into the bush to collect mai (bush foods) and return to the cave to process them. The minymas (women) would teach the kungkas (girls) this knowledge so they could teach their children, and so on ad infinitem. The cave floor has smooth areas where seeds were pounded with round stones, The flour was then mixed with water and the dough cooked in hot coals ro produce nyuma (flat bread). Their ancestors, the Mala people, brought their food to share. For generations, they continued the tradition. Men would bring kuka (meat) and the women nyuma, fruit, and other mai. People would collect their share, delivering it to their family groups and the old people's cave. Food would also be sent to the nyiinka (bush boys) around the corner.

Tjilpi Pampa Kulpi

The Old people's cave. This is where the old people sat. The ceiling is blackened from their fires. During mala ceremonies the men who were too old to participate would rest in this cave. They would make sure the women and children did not enter the men's ceremonial areas. Their spirits are still here. They had their spears, weapons, and tools with them, and they would cook up malu (kangaroo) and other food their children and grandchildren would bring them. They would tell stories and teach the children not to go running off, to stay in camp.

Kantju Gorge

This waterhole was the main source of water during the mala ceremonies and many generations of people and wildlife have depended on it for survival. The indigenous people always "approach from the side, so as not to frighten any animals away". Francesca explained that the Anangu hunted emu here. "You never hunt them on the way to the hole (you don't want to teach them that it is dangerous), and you also never take all of them. Just a couple from the back." They hunted the emu by dropping from the trees. Because the emu are big predatory birds, they are not scared of anything coming at them from the sky, so they have no need to look up. One of our crew piped up: "they were brave men: emus are big scary birds if they come at you" "He got chased by one" his wife explained. Francesca asked in a clearly mocking tone "you've been chased by an emu? What happened?" There was a pause. "Don't try to feed them" was all he could say.

The Mala story

(Mala is rabbit-sized wallaby, extinct in the wild since 2000. There is a program to bring them back, but the feral cats and foxes largely responsible for their demise are still a challenge.)

The Mala people came from the north and could see Uluru. It looked like a good place to stay a while and make inma. The men raised a Ngaltawata (ceremonial pole) to begin the inma. In the middle of the preparations, two Wintalka men from the west approached and invited the Mala people to join their inma in their country. The Mala men said no, explaining that their ceremony had begun and could not be stopped. The disappointed Wintalka men went back and told their people. They summoned up an evil spirit, a huge dingo called Kurpany, to destroy the Mala inma. As Kurpany travelled towards Uluru he changed into many forms, from wind to mikara (bark) to tjulpu (bird) and leaves so that he could not be seen by anyone. He was mamu, a ghost. Luurnpa (kingfisher woman) was the first to spot him. She warned the Mala people but they didn't listen—they were too busy with their ceremony. Kurpany arrived and attacked the men in this cave. Four were killed and they turned to stone. The remaining Mala people people fled to the south with Kurpany chasing them. You can still see these men, with their white hair and beards set in the stone of the back wall. There spirit is also still here. The next chapter of the story is in South Australia. So the Malawati (wallaby men) represents the Mala people who have died, but also the ones who have gone south. The story teaches the kids about holding ceremonies, but also introduces them to Lofa, the kingfisher woman.

Kulpi Watiku.

This is the senior men's cave. They made their fires here and camped, busily preparing for inma (ceremony). They fixed their tools with malu pulku (kangaroo sinew) and kiti (spinifex resin). From here the men could keep an eye on the nyiinka (bush boys) in the cave around the corner and watch out for men coming back from a hunt with food.

These are the four Mala men who were killed by Guta/Corpa and turned to stone.

These are the four Mala men who were killed by Guta/Corpa and turned to stone.The men had different tools: boomerangs, clubs, spears. The boomerangs here did not need to come back because it is easy to fetch them in this wide-open country. Instead the boomerangs are big and heavy, designed to break bones, and could only be thrown by strong men. The 7-shaped boomerang caught on one leg of something running (such as an emu) and then swung around to break the other one, or at the very least trip it up. Now wounded, the men could follow the tracks of the animal until they inevitably caught up with it. The spears were also made from wood, even the tip, made from Malga, which contains a toxin which weakened the prey, again making it easier to catch.

When the Mala ancestors first arrived at Uluru, nyiinka (bush boys) camped here in this cave. A nyiinka is a boy who is ready to learn how to become a wati (man). Nyiinka are taught how to travel and survive by their grandfathers and elders, and separated from the rest of their families for this period. These teachers were not necessarily the oldest people, though that was common, but they were the wisest, the role models, the ones with the most knowledge in the community, and responsible for transferring this knowledge to the new generations. Traditionally this stage could last several years until a boy proved his hunting skills, self-reliance, and discipline. When they were not out hunting, nyiinka stayed in the cave.

Kulpi Mutitjulu (Family Cave)

The family cave. For many generations, Anangu families camped here. The men would hunt for kuku (meat) and the women and children would collect mai (bush foods). The food would be brought back here to share. At night around the campfire, people told stories, teaching the children about this place, and painting on the rock. Today these stories are still kept and handed down to the children.

Generations of grandfathers painted these pictures, like a teacher uses a school blackboard, to teach nyiinka how to track and

Generations of grandfathers painted these pictures, like a teacher uses a school blackboard, to teach nyiinka how to track and hunt kuka (game). Nyiinka would then be taken into the bush to learn about the country—where the water holes are, where to find

animals, where to source materials for their tools and weapons.

The colors of the paint come from a variety of materials. Tutu (red ochre) and untanu (yellow ochre) are iron-stained clays that were very valuable and traded across the land. Burnt kurkara (desert oak) provides purka (black charcoal), and tjunpa/unu (white ash). The dry materials were placed on a flat stone, crushed, and mixed with kapi (water).

Francesca: The pigments were mixed with animal fat or water. It is obvious that there are a lot of layers of paintings here. Francesca explained that the Anangu have explained the meaning of some of these symbols. When they paint, they paint what they see from above. So when painting a kangaroo, they don't paint the whole animal, they paint the tracks—so they could teach the nyiinka how to follow the tracks. For example two parallel lines indicate an animal's tracks. They would paint the full kangaroo when teaching what part of the kangaroo to eat.

These are kangaroo (hopping) but these white ones over here are emu. And there are some more emu tracks down there in yellow, and some dingo tracks here, in yellow also. And then over here, this mickey mouse-like thing is the introduced camel. Since we know the camel was introduced in 1840, this painting must post-date that time. Another thing you see everywhere, even on canvas, are these concentric circles. Once again taken from above this is a water hole (with its ripples). This symbol also means meeting place, or other place of importance. Over here you can see them all connected with some lines, so this is a journey or a map. This yellow C is actually a person, because again they don't paint the actual person, they paint the tracks, and when you sit in the sand, you leave this C or U-shape in the sand. This is also a common theme on canvas, along with tools. There is a bowl, and the straight line is a digging stick. Bowls represent women, spears and boomerangs represent men. A C with no other symbol is an uninitiated person, a child.

Then over here you see that there is no painting on this side of the rock. Early tour guides threw water on the paintings to wash away the dust and to enhance the color for the less-sensitive cameras of the time, with inevitable consequences.

Kapi Mutitjulu (Waterhole)

The permanent waterhole of Kapi Mutitjulu. The Anangu traditionally came to Kapi Mutitjulu to drink water, and hunt animals seeking water. When it rains, waterfalls cascade off the sides if the rock,

The permanent waterhole of Kapi Mutitjulu. The Anangu traditionally came to Kapi Mutitjulu to drink water, and hunt animals seeking water. When it rains, waterfalls cascade off the sides if the rock, creating creeks. Anangu believe that the cascading shape of the rock was formed by their ancestor, Kuniya (a python woman) who bent down and placed her knee (muti) on the ground.

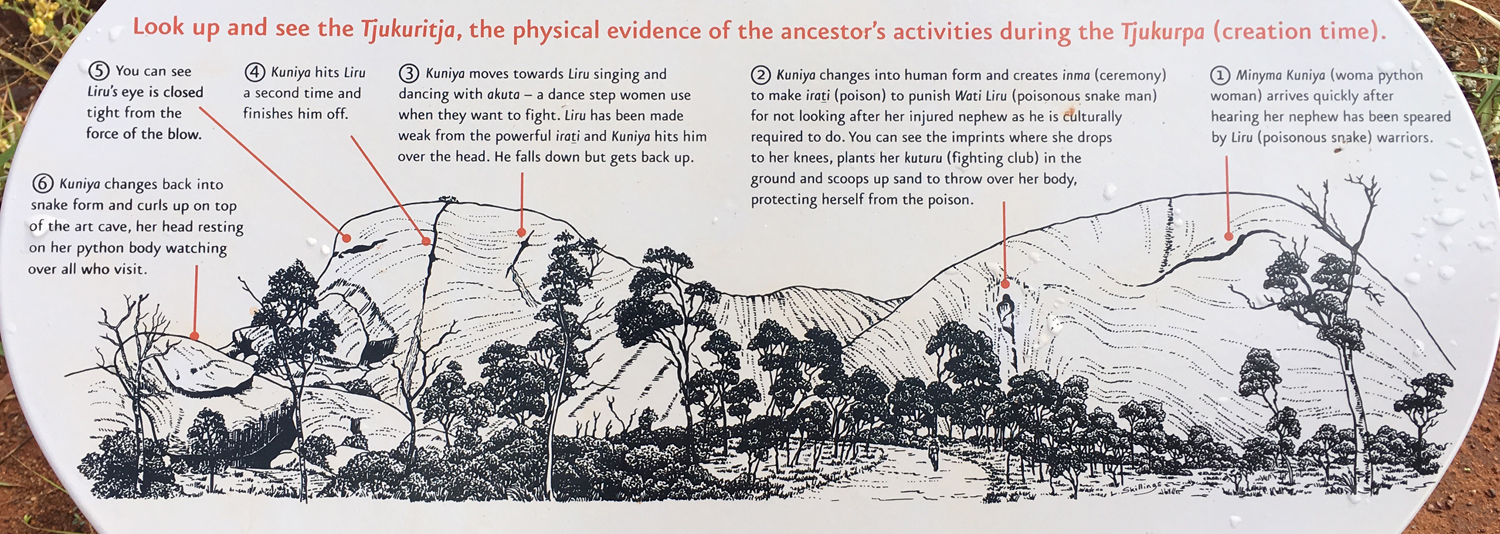

The caves and rock formations of Kulpi Mutitjulu represent the journeys, battles and adventures of Minyma Kuniya (python woman) and Wati Liru (poisonous snake man).

This story and the others that visitors are told are at a level children are taught, as they start to learn about Tjukurpa. As the children grow, so does their responsibility, and so they are taught deeper and deeper levels. This is the story as told by Francesca.

Notice Liru's Eye (5) and the two cracks created by Kuniya as she battled Liru (4) and (3) from the interpretive board above.

Notice Liru's Eye (5) and the two cracks created by Kuniya as she battled Liru (4) and (3) from the interpretive board above.The story is about two snakes. One of the snakes is a woma python called Minyma Kuniya. The other is a very bad snake that can be any venomous snake, called Wati Liru, and it's a man. The story says that Minyma Kuniya was travelling here from the east. At some point she had a bad feeling in her stomach, a feeling that something bad was happening at Uluru, and she had to come here. So she created inma, a ceremony. She took all her eggs and put them around her neck like a necklace, and then left them at Kuniya Piti. (I think Francesca showed us the eggs—a small pile of boulders. Kuniya Piti was right at the start of our walk but I did not photograph them, probably because we were not allowed to take photographs.) As Minyma Kuniya made her way here, her nephew was getting chased by the Wati Liru because he had broken the law. When you break the law in this country you get punished. As simple as that. The punishment is a spear through the thigh, which you then have to pull out through the soft part. He didn't really want to get punished so he started running away. But the Wati Liru chased him, throwing spears. He dodged a few, but in the end he got hit. Once you get hit, someone is assigned to take care of you. You don't have to die, you only have to learn the lesson. So there is always someone taking care of you. So this Wati Liru was nominated to take care of him, but no surprise he did not do his job. So when Minyma Kuniya finally arrived and saw that he was not taking care of the nephew, she got very angry. She wanted to punish him, but to do that she had to make herself powerful, because Wati Liru was a very bad man. So she turned herself into human form and she started another inma, another ceremony, so she sat in the sand like this, took her wana, her digging stick, and planted it between her legs, then scooped a bit of sand and threw it on herself to create iati, poison. So everything I'm saying is on the rock. If you look up here you see a set of dark marks that look like a snake. That's Minyma Kuniya travelling here from the east. Down there all those indentations in the rock, that's her ceremony, see the C with little hole in the middle, with a little hole underneath.

So after that, Minyma Kuniya was strong, and she could confront Wati Liru. So she started an acunta, a war dance. She took her wana, and she hit Wati Liru. You see the first cut here, a little one, then Wati Liru stood up again, ready to fight, so she needed to hit him a second time, making this big big crack, and this time she killed him. See up there, that's his closed eye, because he is dead. So at this point Minyma Kuniya goes back to her nephew, takes him in her arms and takes him to the water down there.

After Minyma Kuniya defeated Wati Liru, her spirit combined with her nephew's and together they became Wanampi the rainbow serpent (water snake). Wanampi still lives here today and has the power to control the source of this precious water. When Wanampi is happy we have water, when Wanampi is not happy, we don't have water. This is the most reliable kapi (water) around the base of Uluru. In traditional times Anangu would sing out "kuka kuka" and Wanampi would release the kapi and let it flow into the waterhole. As with all water sources in the desert, this waterhole is a place of great respect and treated as sacred. Swimming, polluting, or scaring the animals away would threaten the survival of the people. Today, wildlife still depend on it for survival. Minyma Kuniya is still here: if you look about the cave, the big boulder, does it look like a snake to you? You can see the body all curled up, and the head on the top, and that's Minyma Kuniya. She's still here, taking care of all of us.

Chukochapi

At one point we stopped for the packed lunch we had been handed when we set out, and Claudia poked around and between hers and mine found enough to snack on. At another point we were close enough to a parking lot that we encounted a bunch of other tourists, and another time we were overtaken by a platoon of Segues. Why do I hate them so much? They are perfect for allowing folks to enjoy this trip without needing to be fit enough to walk ten miles. But I do. However apart from these brief interuptions, we were just wondering along on our own, enjoying the ever-changing shapes and colors, and listening to Francesca retelling these ancient stories. Lovely.

The Anini people say that there is a marsupial mole living here, Glandalopian? marsupial mole who dug all these holes and caves in the rock.

The Anini people say that there is a marsupial mole living here, Glandalopian? marsupial mole who dug all these holes and caves in the rock.Francesca: So you see we look at the rock here and we see algae, and this is the only place where you can see it. The Anani have a story about a blue-tongued lizard, Lungkata who camped in the round cave at the very top there. He got hungry, and came down looking for food, but he couldn't find any, but further down in a cave he found a Kalia, an emu. The emu was dragging a spear. He knew that therefore someone else was hunting the emu, and therefore he should not take it. But he was very hungry so he took it anyway, and came down here to start a fire and cook the emu. Soon two Pampalala men arrived. Pampalala is a crested bail bird. They saw the fire and approached it. Lungata had hidden all the pieces of emu, so when the men asked if he'd seen their emu, he said no. The men moved on, but soon realized that they had been fooled by Lungkata, and turned back. Meanwhile, Lungkata had gathered up the pieces, and headed up to his cave. But he dropped some on the way. The Pamapalala saw the evidence and shouted up to Lungkata to give them their emu back. But he didn't care, he was up high in his cave eating his meat. So the Pampalala started a huge fire, sending all the smoke up into the cave, so that Lungkata could not breath. As he leaned forward to try to get air, he fell off the rock. As he bounced his way down, his skin stuck to the now very hot rock and was left behind. This is a beautiful story that tells the people two very important things: don't climb; don't steal another man's emu.

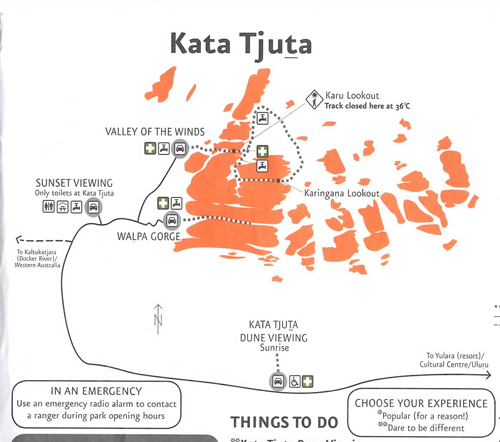

Kata Tjuta

York Minster has a vibe even I can sense. Avebury (Stone) Circle has a vibe. Uluru has a vibe. Not the same vibe, but a vibe nevertheless. You can practically hear "come home" whispering on the breeze. Its warm rock walls provide a palpable sensation of safety and security when you are close. Kata Tjuta provided no such thing.

By the time we were driving out there after our long morning at Uluru, it was hot. We pulled in to a look out parking lot where a path led about 100 yds up to the top of a sanddune but CMT not only wouldn't get out of the car, she insisted I leave the engine running and the AC on while I took a brisk walk.

The color contrast between the brilliant blue sky, the ochre red earth, the shiny trunks of the eucalypts in every shade from white to orange to deep brown, all crowned and edged with a froth of bright green leaves, the sharp smell of their oil in the air, and perhaps a pair of kangaroo perked up and staring at us from the shade of the trees is my thumbnail picture of Australia. Except for the lack of kangaroo, this spot was the essence of that image. Claudia's Australia definition was simpler: "Cattle Stations and roadhouses sum up the outback".

Then on to Kata Tjuta itself. We'd agreed to take a swing at Walpa Gorge, the shorter of two walks into the rocks, and CMT told me to push on, she'd see how far she felt like going. Despite the air temperature, and in stark contrast to Uluru, these rocks seemed cold, lifeless, and forbiding. The going underfoot was mostly rubble giving the ankles a good workout and threatening to twist them at every step.

From the signage: "The combination of puli (rock) and karu (creek) areas provide a special desert refuge for animals. The towering puli walls shelter the moisture-rich karu from the extreme elements. This is kanyala (hill kangaroo) territory. Muscular and robust, they bound effortlessly up the puli to their caves. Highly adapted to the puli they rarely leave even in drought. They can locate and dig for underground water, digest the spiky spinifex grass and recycle their urea, allowing them to survive on nutrient-poor food in hard times. Tjilkamata (echidna) also come here to drink. They are most often seen after rain, taking advantage of the explosion in ant numbers above ground. (RT: needless to say, despite the recent rains, we saw neither hide nor hair of any fauna, except a small parliament of ravens squabbling as ever.)

Water and wind erosion continue to slowly sculpt this spectacular ancient gorge. This special place provides shady caves, rocky slopes and moisture - a rare combination in the desert. Many plants that grow here are rare - some are found nowhere else. Highly specialized, the plants can only flourish in these very specific environmental conditions. In the shade, Mingkulpa (native tobacco, Nicotiana gossei) is found in moist, shady, rocky areas. The plant is dried and mixed with white ash to be chewed. Highly prized, it is used to relieve hunger, thirst and fatigue and to produce a general feeling of well-being." (RT: sounds just like regular tobacco.) On the slopes the vine-like stems of urtjanpa, the rare spearwoodvine, (Pandorea doratoxylon) are ideal to make kulata (spear) shafts. (RT: a shocker, I know.) Long, flexible, and light-weight, the stems are straightened and hardened over a fire. Kaliwara (Kata Tjuta wattle, Acacia olgana) grows along the creek. The Pitjantjatjara name describes the leaves. Kali meaning bent (leaf tips) and wara meaning long."

I did as I was bidden, and pressed on all the way to the end of the path, where a platform marked a definitive terminus and also afforded a good view up ahead to where the two sides of the gorge closed to a small shrub-covered gap. I hung around for a few minutes admiring the pluck of a couple of German kids, both under ten but properly attired with their cute little walking boots and sensible hats, as they horsed around waiting for their parents to turn back—whereupon they jumped down the steps and were soon out of sight leading the way home, followed closely by their parents, and then after a few more moments of solitude on the platform, by me. Almost immediately I was pleasantly surprised to meet Claudia still plodding her weary way. So of course I turned around and we returned to the lookout together.

For some reason the puli walls seemed even more intimidating on the way back, positively angry even. But soon enough we'd retraced the rocky path and its easier elevated sections that protected some of the wetter areas and eased the crossing of some of the deeper troughs in the gorge floor. Back to the car, water, and AC, then back to the hotel for a welcome bath before Tali Wiru: The Big Night Out.

Tali Wiru: The Big Night Out

The crowd for the Field of Lights show was crazy large and so, therefore, was their bus. Once they departed, there was a much more reasonable half dozen folks left. I was delighted to discover that our own bus was the oversized SUV that I'd seen around town. It made a couple more stops and then we headed out of town. It was a motley crew, some dressed up, others in jeans. Mostly couples but one family in the usual combinations of talking to each other or not, more unusually with the dad trying to chivvy everyone along, but the mom pretty much pissed at everyone. They did a great job of keeping the drama to the confines of the back of the bus and then at their table.

The driver and co-pilot were both very young, and not all that experienced at their jobs in general, and driving this big truck in particular. But they delivered us safe and sound, although with the gear-box perhaps less so. The base of the sand dune-restaurant was at the end of several miles of dirt track that provided a small measure of justification for the ruggedness of the vehicle. We piled out to be introduced to our hostess, a large (I'm being kind) woman in an incongruously fancy gown and heels, who gave us the rundown for the evening. We would eat, there would be entertainment, we would need to climb the sand dune. It was a spectacular setting and the lighting, both natural and man-made, was perfect.

"Tali Wiru, (beautiful dune) in Anangu, encapsulates the magic of fine dining under the Southern Desert sky. The open-air restaurant has magnificent views of Uluru and the distant domes of Kata Tjuta, and 'for unique ambiance there's the stillness of the desert at night'." So says the brochure.

We were extremely lucky. The three nights prior to our arrival the dinner had been cancelled because of bad weather, and although they had managed to start up again the previous night, when we were there it was still moody and unseasonably cool. But it was absolutely warm enough to be comfortable al fresco, and the light show around Uluru was spec-tac-u-lar. Internal lighting in the clouds behind it constantly lit up their pillows, providing an ever-changing background of color and light, with the dark silhouette of Uluru in front.

The first stop was the kitchen level. In front of the kitchen was a patio area complete with fire-pit, and beyond that, at a safe distance was a didgeridoo player, and beyond him, on the horizon, the star of the show: Uluru. As we sipped our welcoming bubbly, the waitresses brought around an amuse bouche: wattleseed humus with burnt butter on a little biscuit. Our first native-influenced sample. Then came the canapes, including scallops, kangaroo, and crocodile. The scallops came with my second serving of green ants. This time they were entombed in a syrup that secured them to the top of the scallop. Oh-my-god delicious. They added the same hint of citrus that I'd noticed in the gin the night before. Another star appeared, the chef himself, craddling a native collecting basket. In it was a selection of the indigenous ingredients that the chef and his partner were incorporating into the night's menu. He was great. Amongst other things he introduced us to finger (lime) caviar, an interesting fruit that when cut open reveal their globular juice vesicles (wikipedia's words, not mine) - the lime-flavored caviar. I noticed that the green ants were not part of this little demo. Live ones were going to have to wait for our rain forest excursions.

Eventually we climbed to the top of the dune, and the dining platform. I ordered the wallaby and the Wagyu beef, Claudia the Moreton Bay bug and the toothfish. While we waited, the second amuse arrived, a parsnip espuma (you and I might have called it hummus) and the first glass of paired wines. Almost as soon as our table lamps were lit they became a landing pad for an ever-increasing number of partiers. Fortunately for us, neither we nor our food seemed to be on their menu so once landed, they stuck to their lampshade dance floor.

Slowly the courses arrived, and with them their paired wine offerings, which meant that I was forced to consume a glass per course, plus naturally I needed at least to try Claudia's. They were all excellent, but that's really no excuse. By the time my cheese selection arrived with its obligatory glass of port, it was clear even to me that I'd been a tad overserved. And so it was fairly predictable that while the temperature of the dunes stayed warmer than I expected for this desert setting (and there were a fleet of propane heaters on stand-by just in case) the same could not be said for our table, where the temperature was dropping rapidly and by dessert was down-right frosty. Even the waiters had given up their attempts to chat.

As soon as the plates were cleared, the lamps were extinguished, their guests flew off into the night, and no one needed to make conversation anymore because the astronomer/story-teller took the stage. Call me uncharitable, but the most memorable thing about the show was his laser pointer. To my amazement, and I had to try it for myself when I got home, he could use it to point out stars in the sky as if they were painted on the ceiling, even drawing little circles around them. I could have watched it all night. He showed us a bunch of constellations in this alien sky, and we learned how to find true north using the Southern Cross (much more complicated than the good ol' north star) but it is what it is. He told a few stories but had an annoying habit of adding "Yes" as a one-word sentence between the other more informative ones. It was a statement not a question, as if having to constantly assure himself that he was telling truths, or that he had remembered the right lines, in the right order.

Show over, we rolled down the hill to the foyer/kitchen level, where our hostess was waiting with cognac and a fire to sit around while we enjoyed it. Some of us were not in the mood to sit and enjoy anything by then, and instead pointedly started the queue for the bus. In my defense, in addition to the wine being spectacular, and failing to factor in the complementary cognac, I was by no means alone. At least one other guest was so well-refreshed she had to lie down on the path in her place in Claudia's line while we waited for the bus to arrive, and once it did, several more failed to negotiate a clean entry through the bus door. All-in-all I thought I handled myself commendably, but of course no one was asking my opinion.

I have to say, looking back, there was a starker contrast between the brochure's claim that "the contrast between the spectacular natural setting and the world-class gastronomic adventure on your plate is simply awe-inspiring" which were indeed stunning, and the support staff, who were decidely less so. It was as if the union staff suddenly went on strike and the company had spent the afternoon scrambling to drum up anyone available to fill the positions. Nothing was exactly wrong, but it just didn't click. It was by far the most expensive meal we had in Australia, and yet every question we had for the waiter required a trip back to the kitchen to get answered. Our waiter only had a couple of tables to attend, and only two types of wine to juggle with each course, but still couldn't remember which one we had chosen when they came around with refills. We heard four people play the didgeridoo by the time we returned to the US, and this young man was the only one who was being paid solely for the purpose of playing it. Yet he was by far the least entertaining/proficient of the players. When I went over to chat and to thank him, he admitted he was a beginner. The after-dinner story teller as I already complained had speech mannerisms that made it hard to follow and impossible to remember anything he said. All very minor in their way, but that's really the point. A feature of top-class experiences is not-even-minor-issues. Very strange, and definitely took the bloom off the rose. But a rose nevertheless.

|

|

The Road to Alice

We were not in a hurry, but on the other hand we had a plane to catch, and 450km / 280 miles to the airport. So we pretty much rolled out of bed and got on the road. Which meant the first stop was gas and coffee.

The two women of a certain age behind the counter at Curtin Springs were delightful, but acted as if we were the first people ever to order coffee. They had to make it by hand, and I'm talking spooning instant coffee into a mug of boiling water, not an expresso machine. Likewise someone had to come out and unlock the pump so we could gas up. As usual the place looked like it was designed for a hundred times as many people, complete with a huge aviary with cockatoos and parrots engaged in their usual arguments high up in the roof top.

|

|

Then on to Stuart's Well for lunch. Jim's Place. Back on the main highway, and with more than half the driving done we could relax a little and grab some lunch. Especially when I discovered both crocodile and camel on the menu. A sign outside the roadhouse proclaimed that Jim and his father Jack cut the first track through 100km of sandhills and dense bush to Kings Canyon (on the dirt road to Uluru, and a very popular side trip from the surfaced one). They used a single "vehicle with a blade" which was supposed to be in front of the store, but was not, so we were left to imagine a pickup with a snow plow on the front, but no idea how accurate that vision was. A smaller sign outside the door even made CMT laugh. Inside was a veritable oasis, with its lush greenery, (tiny) pool and hot tub. The sulphur-crested cockatoo would have completed the picture if it had been sat in the tree, but instead it was chained to its perch waiting to bite the hand that fed it. I settled for a camelburger. This was the "plain" one. Another winner I'd be happy to eat again at least once a week for ever.

Almost as soon as we were back on the road, the scenery changed as the landscape started to ripple. Dry river beds ran under the road in all the low spots, and eventually a more distinctive bridge structure marked the crossing of the River Todd, also dry. The Todd runs through Alice Springs and had been made memorable in my trip research by a description of the Henley on Todd Regatta, a boat race run by carrying the boats along the sandy dry river bed every spring. This was amusing enough as a concept, ("it began – and continues – cautiously as a joke at the expense of the original British settlers and the formal atmosphere of the British river races ") but my favorite part of the description was the fact that one year the boat race had to be cancelled‐because there was water in the river. I guess it's a pretty big deal, as I now discover that not only is it in Wikipedia but it has its own Facebook page. Defo on the bucket list for next time.  "The Alice" was by far the most disappointing venue of the trip. It's a good job we'd only allowed an hour or two. Originally that was because we figured this little outback town would have few sights to see, and once we'd poked our heads into, say, the old telegraph office, and found a dusty old saloon to have an "Ice Cold in Alice" pilsner, we'd be done. Instead it was a sprawling ugly metropolis, a sort of Reading In The Desert. When we finally found what seemed to be the town center, it was shut. Pretty much all of it. We stopped someone to ask for advice/directions and he'd only been in town a couple of hours himself. Spirits plummeting, we finally found a bar that did a half way decent job of pretending to be a dusty old saloon. I was impressed to see that they were adverting "this week's gin and tonic infusion: cucumber and basil" and I would have been happy to sit there for a couple of hours and sample a few. But we were on a timetable, and I was on probation, so I settled for a glass of LazyYak, my "Ice Cold in Alice" and they did an excellent job on a cup of tea for CMT. Then it was time to high-tail it to the airport, dump the car, and another wonderful experience of two minutes from check-in to sitting at the gate. We found a kangaroo pin for C's new hat. Next stop: Queensland. |

|

|

|