| Preface | Perth | Stuart Highway | Uluru | Port Douglas | Sydney | Sturt Highway | Kangaroo Island | Indian Pacific | Perth |

If pre-history is the time before recording-keeping, and the ability (and need) to be able to account for the passing of the years, Australia remained pre-historic until the afternoon of January 26, 1788 when a fleet of 11 vessels carrying 1030 souls including 548 male and 188 female convicts, under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip in his flagship Sirius entered Port Jackson, or as we now know it, Sydney Harbor. The United States of America was already more than 10 years old.

The newness of the (European) presence is all the more stark when compared to the land itself. Devoid of the mountain-making forces of volcanoes and plate tectonics, most of its topography has literally washed away, leaving its ancient remains flat as a pancake. Perhaps one gets the same feeling in the American west, but there is just so much more countryside in Australia, constantly reminding you of how ancient it is.

Australia Old and New

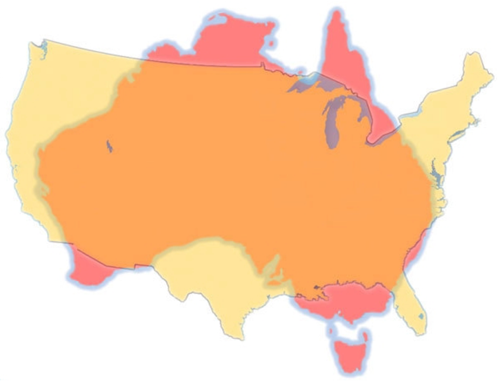

To introduce Australia the first thing we need to do to get a proper idea of scale. The overall land mass of Australia is a little smaller than that of the continental United States, but a coast-to-coast trip such as this one is very much on par with a coast-to-coast trip across the US.

By contrast, there is no comparison between their population density. In 2017 the population of US was 320 million whereas the population of Australia was 24 million, making it the third least-populated country after Namibia and Mongolia. Not only that, but the vast majority of the population lives clustered on the east coast between Sydney and Melbourne, leaving the other 95% of the continent pretty much deserted.

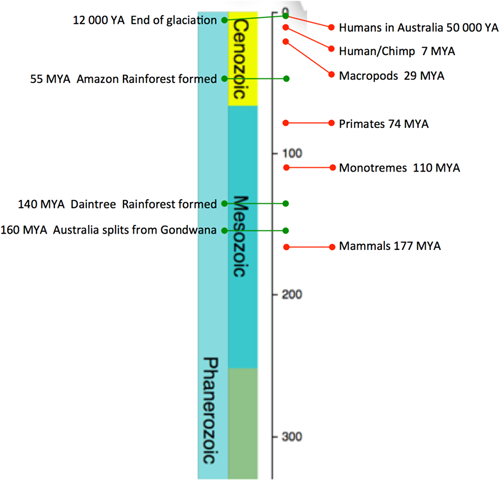

Australia is old. Along with India and Antarctica, Australia separated from the other continents 140 million years ago when Gondwana broke up. Mammals were a fairly new idea, and most of the early marsupials were carried away on this continental ark, leaving only the possums as their sole relative back in what was to become South America. India soon split off to head north for its headlong crash into south asia where it continues to push up the Himalayas today. Now completely isolated, and without the competition of shrews, mice, rats, rabbits and deer, to say nothing of their predators, the marsupials were free to beat their own evolutionary path. Similarly, the Daintree rainforest in Northern Queensland was already flourishing and continued uninterupted right through the ice age. The oldest estimates for the Amazon rain forest by contrast place it at around 40 million years old—not even close. The Amazon's diversity is to a certain extent a product of the waxing and waning of its climate, whereas the Daintree's consistancy preserves many of the world's oldest plant species, and the ancestors of many of the flowering plants of the other continents.

Even the presence of homo sapiens is ancient compared to other populations. Aborigines arrived at least ~30,000 years ago— long before the end of the ice age, and as much as 10,000 years before American Indians arrived on the American continent. As Jared Steele explains in his highly recommended book "Guns, Germs and Steel" the harsher the conditions, the poorer the environment, the harder it was for tribes to develop technologically. The aborigines were, and are, absolute masters of their domain, but that domain is one of the harshest on the planet and as a consequence they were still enjoying a stone age existance when the white man finally appeared in 1770.*

We spent most of our time out in this old world, absorbing the geology, the flora and fauna, and on several occasions learning about the aboriginal culture, but ultimately we were still never far from an automobile, or a gas station, or a tavern. And of course we spent some time in the big cities, all of which means that we were face to face with the contrast of the "white" Australia: it is young. America was already fomenting revolution by the time Captain James Cook landed on, and claimed, the east coast of Australia for Great Britain in 1770. In 1783 English convicts were no longer permitted to be transported to America and parliament was forced to look around for another location to offload the sinning classes. The first convicts arrive in Botany Bay (Sydney) on January 20, 1788. It wasn't until nearly one hundred years later on 19 July 1873 when the first white person arrived at Uluru.

So what was our goal? My goal was to share with Claudia the highlights from my first visit while thoroughly enjoying all the new things she would add this time around. Vast as it is, CMT wanted to see it all "I'm not going all that way twice." I think this was actually easier to contemplate that it might be elsewhere, because with limited man-man must-sees which of course are all unique, one section of a 2,000 mile desert is fairly similar to the next—especially if you take a train across the whole thing. Natural phenomena like the Great Barrier Reef, Uluru or the Remarkables are much fewer and further between. Likewise without the twitcher's obsession to see not just a spotted pardalote but also its endangered cousin the forty-spotted pardalote, seeing bunches of kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, and monotremes on numerous occasions comfortably checked our unique-to-Oz check boxes.

So put all those together, add the spectacular Circular Quay in Sydney—the bridge and Opera House—along with the botanical gardens we accidently visited in all three of the major cities on our route and you've got yourself the trip of a lifetime: Return to Oz.

* In "Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind" Yuval Noah Harari suggests that humankind's ability and willingness to change the climate began not with the industrial revolution but with what he calls the cognitive revolution—the appearance of homo sapiens 70 000 years ago. I bring this up here because the single most important feature (and continuous thread) of this revolution was the ability to cut down trees. There is mounting evidence that as soon as homo sapiens arrives the clearing begins. The idea that the first Australians arrived on a continent with a thriving flora and fauna, and that it is they themselves who therefore created the "sun-burnt country" we know today is as scary a premonition for today's crisis as anything I can think of.