| Preface | Perth | Stuart Highway | Uluru | Port Douglas | Sydney | Sturt Highway | Kangaroo Island | Indian Pacific | Perth |

Part 1:

- Julaten: Our tropical retreat

- Mossman Gorge: Chip's forest walk

- Daintree River: Murray's boat tour

Part 2:

- Cape Tribulation: Nick's Day Tour

- Great Barrier Reef

- Port Douglas (my unplanned "rest day")

Nick and Cape Tribulation

Our second rainforest day was a whole day excursion with Nicholas Fox of Daintree Safaris who would take us into the rainforest proper, looking for birds and wildlife in general, and cassowaries in particular.

Originally supposed to pick us up at the lodge, our hostess Wendy had arranged with Nick that we would meet him in a supermarket parking lot thus allowing me to do the switchback driving up and down the mountain. Needless to say he was on time and was waiting for us when we got there with a couple of minutes to spare. We would cross the Daintree and push on up towards Cape Tribulation, do a couple of walks, visit Tribulation beach itself, and finish up with a boat trip.

As soon as Nick opened his mouth, I knew he was an English public school boy. It was more than a little surprising then for him to explain that he was Spanish, son of a "coffee grower". After a little more prodding he conceded that he'd been "incarcerated in the English system for 10 years 9 months and 17 days", meaning from when he was 7 or 8 years old. I knew it! The only thing mother nature abhors more than a vacuum is abnormality, and public school boys are no exception. For many, if not most, it is a system that produces life-long bonds and a priceless network. Like any other school system, there are many variants of acceptable characters from jocks to poets, from academics to artists, but you have to be able to play the game somehow. If you lack the ability to pick up on social cues, or are the sort of loner who would rather ignore them than "run with the herd" it can be hell. And unlike other school systems, it is a 24x7 hell. Nick was someone who makes horses nervous and he would undoubtably have had the same effect on his peers. Which isn't to say I didn't like him. I did. We both did. He had a wonderful dry wit that made us both laugh out loud and he provided us with a first-class day which we loved every minute of. Nothing was too much trouble. When it looked like it was going to rain, he hurried back to the car and fetched umbrellas. When it stopped looking like it was going to rain, he took them back and carried them all.

So why the negative description? It's not meant to be negative, it is meant to explain, not to say excuse, his rather odd delivery. It was as if we were in a play. A play that lasted all day, and for which he had learned all his lines. I asked a question in the middle of one particular monolog, and he asked me to wait while he finished, and he literally picked up right where he had left off. They were great lines, often laugh out loud funny, and he clearly relished the language. Why use a one-syllable word when a three-syllable word will do? Well for one thing it was often much more amusing.

Daintree and the Crocodiles

We crossed the Daintree on the perfect conveyance: a cable ferry. It was waiting on our bank so we drove straight on. There was room for three or four cars but we didn't wait for them. The platform steadily pulled itself across the river at a jaunty angle that hinted at the strength of the current. Along the coastline north of the Daintree River, tropical forest grows right down to the edge of the sea. The roads north of the river wind through areas of lush forest, and have been designed to minimize impacts on this ancient ecosystem, which among other things mean that they are narrow, steep-sided and minimally maintained. From a total of 19 primitive flowering plant families on Earth, 12 families are represented in the Daintree region making the highest concentration of these plants worldwide. These ancient plant families may well hold the secret to a number of unanswered questions regarding the origins of the flowering plants – plants on which the human race depends for food and medicines.

Because we drove straight on, we did not see the sign on the river bank until we returned and had time to get out of the car. "Feel free to stretch your legs but don't even think of getting close to the water" our second crocodile warning of the day, and a much more earnest one. The sign says "Never disturb crocodile nests." Seems like good advice. More ominously it goes on to warn that they "may be present in swimming holes." So while we wait for the ferry, time for a brief rathole on crocs.

Little different from their prehistoric ancestors that stalked the earth before the dinosaur age, crocodiles have survived major upheavals such as the breakup of the world's continents and the ice ages. Like too many other species, today they face their greatest threat, with many of the world's 22 species of crocodiles and alligators hunted to the brink of extinction.

Two species of crocodile live in Queensland. The freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus johnstoni) and the estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). Adult crocodiles play an important role at the top of the wetland food chain, if they survive the 12 (female) to 16 (male) years it takes to get there. Younger crocodiles are much further down the food chain and prey to goannas, freshwater turtles, barracuda, sea eagles, and other crocodiles—they are attacked on land, in the water, and from the air. A big male estuarine crocodile can reach 7m (20+ ft) but most are less than 5m. The females build a large mound of vegetation and soil in the grass or fringe forest along the banks of a water course, and inside this temperature-controlled nest she deposits about 50 eggs which she guards fiercely for the 90 days of incubation. The incubation temperature determines the sex of the offspring, with low temperatures producing mostly females, while warmer temperatures produce predominantly males. The young hatchlings squawk at their mother to dig them out, and she often carries them down to the water in her mouth, the safest place they will be for the next 12 to 16 years. Less than 1% make it.

Traditional Aboriginal and Torres Straits people have had a special relationship with crocodiles, making them the subject of stories, songs, dances, and painting. Some groups even regard crocodiles as religious icons or totems, with special powers to protect. Others believe that they are the spirits of their ancestors—an interesting insight into their collective psychy.

The road on the other side was a stark contrast to our normal experience. A different, older world. Streamlets trickled down the crumbling edges, and we splashed through puddles that were probably a permanent feature. It was barely wide enough for one vehicle (though it was a Land Cruiser) and the banks on the landward side were so steep that the ferns brushed the wing mirrors every few seconds. On the other side we were generally only a few trees away from the beach, and sometimes all we could see was water. Nick never wavered, keeping up the constant commentary. "Oh good" he says as he suddenly pulled in at a roadside stand and picked up a handful of the advertized mangosteens, and most of the rambutans that were also on the plate.

Every few minutes we would pass a driveway, rough tracks leading back into the forest. Nick slowed and peered down them. Several times he even backed up to get another look. "Cassawaries." "Twenty years ago they were very rare, but their population has continually increased since then." I was reminded that on our 2005 trip Wayne had spend a week up here just to find one, and failed." Twelve years later they are significantly more plentiful, thanks to protection and preservation by wildlife authorities in the area. Nick reckoned to be successful 4 times out of 5, though a major reason for picking him was his prowess on just this topic. This was going to be a 1 in 5 day, which was disappointing but somehow also it didn't seem right that a couple of amateurs would be able to check off a bird that Wayne had been unable to do, so all-in-all it was a zero sum game.

For many people, the Cassowary’s three-toed feet, amber eyes, casque, and brightly coloured neck are evocative of a dinosaur. They belong to the Ratites, mostly large, flightless birds with a ratite breastbone: the ostrich, rhea, emu, cassowary, and kiwi, together with the extinct moa and elephant bird. The ratites have no keel on their sternum - hence their name which comes from the Latin (ratis) for raft. Without this to anchor their wing muscles they could not fly even if they were to develop suitable wings.

Cassowaries have been recorded as eating over 238 species of plants, and they play an important role in maintaining the diversity of rainforest trees. Cassowaries are one of only a few species that can disperse large rainforest fruits and are the only long distance dispersal agent for large seeded fruits. Cassowaries swallow fruit whole, digesting the pulp, and passing the seeds unharmed in large piles of dung, distributing them over large areas throughout the rainforest. A ready-made fertiliser, the dung helps many kinds of seed to grow. Other animals sometimes feed on the seeds in cassowary droppings, helping to distribute them further. The cassowary’s gentle digestive system, and short intestines, may also help to protect them from absorbing a harmful level of toxins from some of the fruits they eat. The cassowary is considered a keystone species because of its critical role in maintaining the ecological balance of the rainforest. Protecting cassowary habitat and food plants benefits many other rainforest plants and animals. Without cassowaries, some species of rainforest plants would have no means of distribution. If cassowaries were to disappear from an area, some of these species may eventually become locally extinct, threatening other species that depend on them and changing the forest dynamic.

The traditional owners and custodians of the region were the Eastern Kuku Yalanji people. They call the Cape Tribulation area “Kurangee” meaning ‘the place of many cassowaries’. They also named many of the landscapes by how they described it. Examples include Manjal Dimbi (Mount Demi), which means “mountain holding back”, Kaya-biji (Snapper Island) that looks like a gigantic crocodile and Wurrmbu (The Bluff) that has great spiritual significance.

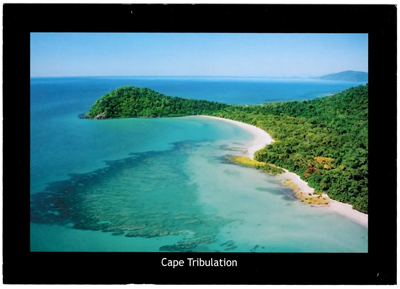

Cape Tribulation

First stop after crossing the river was Tribulation Bay. Between the parking lot and the beach a grove of trees provided shade for a dozen or more picnic tables, a surprising number of which were elaborately set up with table clothes and place settings. Nick sent us through to the beach for a stroll while he set up breakfast. Between the picnic tables and the sand a large rusting sign, which gave it a definite air of neglect, warned of the dangers of crocodile encounters. Nick: "Crocodiles have been around Cape Tribulation since the dinosaur days. While there haven’t been any reported croc sightings on the beach in recent times, we always remind our guests to take sensible precautions to avoid accidents." The beach was classic tropical beach with its azure water, white sand, and backdrop of palms, but it seemed cleaner than usual, with none of the leaf litter, coconuts in various stages of repair and decay, and in the worst cases manmade flotsam that are more typical of the classic deserted beach. A single pair of girls sunbathing two hundred yards up the beach were the only other occupants. We clearly constituted a crowd, because when they noticed us they sat up to put some clothes on then lay back down to pretend we were not there. We respected this by doing likewise, and turned in the other direction to walk down the beach. We found a walkway at the end which led to a little promentary giving a lovely view all the way up the beach.

By the time we got back to the picnic table, Nick had laid out a feast. On a tablecloth of course, with cloth napkins and china. Tea or coffee, homemade (gluten-free) muffins, and the fruit he'd bought at the farm stand. He showed us how to eat the mangosteens by tearing them open to reveal the white fruit segments inside which looked like giant soft garlic cloves. The fruit was crowned with a rosette of 4 to 8 fleshly "petals" (actually remnants of the stigma), which Nick pointed out always predicted the number of fruit segments inside. Both the rambutans and the mangosteens were delicious. By the time we were packing up it felt like the next crew was lining up to take our table. Which was odd: the picnic tables were full, but the beach was empty. As we schlepped the picnic back to the car, a huge Ulysses butterfly fluttered by. At 11+ cm, 4.5in, it is Australia's second largest and fastest butterfly which it demonstrated by settling briefly, then fluttered back passed us putting on a splendid display but its speed and random flight pattern made it impossible to photograph.

|

|

|

|

Cape Tribulation celebrates the location where Captain Cook almost came undone. At around 11pm on 11 June 1770, after passing through Pickersgill Reef, HMS Endeavour ran aground on another reef. The reef is about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) off the mainland. Hence the name: Cook stated "here began all my troubles".

A search of the wreck area in 1969 discovered six abandoned cannons, ballast and an anchor which was discarded by the crew of the Endeavour when attempting to re-float the ship. One of these cannons is on display at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Darling Harbor, Sydney. In my attempts to corroborate Nick's detailed account of the founding and saving of the ship by fothering I came across complete transcripts of Cook's log which were surprisingly readable. Here is his Journal entry for Monday 11 June through Wednesday 13 June 1770.

We stopped at a lookout for a two minute gaze of the view. Nick pointed out Devils Thumb (Manjal Jimalji, a place of cultural significance telling the story of fire creation) and Black Mountain (Kalkajaka) its grey granite boulders blackened by a film of microscopic blue-green algae growing on the exposed surfaces. Once identified, one or other of them stood out from every vista, including just tooling down the main roads. But the real purpose was so he could have a surreptitious cigarette, and so that we could make a lunch choice from a menu he sprited up out of nowhere. Twenty minutes later when we rolled up at the restaurant, they were ready for us. The whole day ran with this sort of military precision.

Part of that precision was that in fact the restaurant was closed that day, because they had a private party—a bus-load of German tourists— but they had still left room for us. We also benefited directly from the group, because part of the lecture they were getting as they dined included a small plateful of fruit samples, and the chef had prepared two for us too.

Finger lime or caviar lime (citrus australasica) Finger lime or caviar lime (citrus australasica)

I think Claudia had a simple salad, which as usual was excellent, and I had settled on kangaroo steak and chips. The kangaroo was definitely something I would have again, but it had that super-lean dryness that some people don't like about buffalo/bison. Since I happily compensate with a mustard lubricant, that was a non-issue. Best of show was the fruit exhibition, both on the plate and a splendid side-show allowing us to examine the finger lime we'd been served in Uluru. Although the little slice we had did not appear to have been cut from a particularly large specimen, what I took to be a piece of grapefruit was in fact apparently from a pomelo, the largest citrus fruit. It is a natural (non-hybrid) citrus fruit, similar in appearance to a large grapefruit, and is one of the original citrus species from which the rest of cultivated citrus have been hybridized. |

On the plate, left to right:

dragon fruit;

passion fruit;

mango;

rambutan (top);

custard apple (bottom);

mangosteen (top);

persimmon (bottom);

pomelo citrus maxima (top);

mamey sapote (bottom).

Note the blue-bottle fly photo bomb bottom left. On the plate, left to right:

dragon fruit;

passion fruit;

mango;

rambutan (top);

custard apple (bottom);

mangosteen (top);

persimmon (bottom);

pomelo citrus maxima (top);

mamey sapote (bottom).

Note the blue-bottle fly photo bomb bottom left.

|

Rainforest Walk

|

We had two rain forest walks, one before and one after lunch. One was in more hilly country and the other through lower-lying marshes and ponds, but the non-stop streaming of facts from Nick, and the overlap of some of the flora and fauna we saw rather blends the two together in my mind, and therefore they are blended together in this narrative also. The rain forest walk was disappointing at first because I had somehow imagined us cutting a path through the rainforest, dodging leeches and snakes. Instead we were on a boardwalk the whole way. Thousands came this way. It was a route that didn't need a map, let alone a guide, so why did we need Nick? Well of course we needed Nick for the same reason you need a guide wherever you are if you want to learn ten or one hundred times as much about the space as you would on your own. And the board walk is not so much to make a forest setting wheelchair accessible as it was to protect the fragile environment we were here to see. At regular intervals boards posted beside the path did their best to educate us—a tall task trying to be chatty and brief enough to appeal to some audiences, while being detailed and long enough to satisfy others. One sign was titled "Wet and Windy Sex". I tried to imagine such a thing in the US, or even in the UK. It went on to describe these ferns, along with the idiosernum one of the most ancient plants on the planet, closely resembling their 300 million year old ancestors. Like the earliest plants, they rely on wind and water to carry their spores away from home. If the spores lodge in a suitable place, they germinate, sending up a tiny leaf. Male and female cells form on the back of the leaf and fertilization takes place. By contrast, instead of leaving fertilization to climate and chance, the more recently evolved flowering plants bribe animals with pollen and nectar to be their sexual go-betweens. Another large sign introduced the walk to its visitors (I've toned it down a little) "This epic rainforest contains a large variety of plants inherited from the ancient stock of Gondwana and some of the ancient plant life in this rainforest are also known as ‘Green Dinosaurs’ because of how old they are. With large fruiting trees, beautiful flowering orchids and over forty species of ferns, there is so much to learn about the wonderful flora located in the Daintree Rainforest." Some towering trees and plants in the rainforest have been standing from the time the dinosaurs roamed the earth. The Kings fern and Idiospermum (Idiot tree) are examples of ancient tree species in the Daintree. One highlight in particular stands out, because I love these cross-references, confirming and expanding on a previous experience. Nick carefully picked an ant off an overhanging leaf. "Green ant. It's used traditionally as a thirst-quencher." With that he gently rubbed its abdomen against his lips. Then he let it go long enough for me to grab it gently as I'd been shown, and gingerly applied the lipstick to my own lips. The sharp, limely flavor indeed made me salivate as advertized. Getting this direct, fresh, unadulerated tasting allowed me to appreciate exactly the role it had played in the flavors of both the appetizer and the gin we had encountered earlier in the trip. Loved it. Best of all, I'd obviously been sufficiently delicate in my handling, because when Nick carefully put the donor back on its leaf, it scurried away apparently none the worse for wear. The only other people we saw on either walk came by soon after that, again a couple with a guide, and Nick took the opportunity (as he never missed) to point out how superior his tour was to the other "rushed" one. |

Strangler fig. Also seen on other continents, but this is a doozy, showing the fig lattice after the strangled host tree has rotted away. Strangler fig. Also seen on other continents, but this is a doozy, showing the fig lattice after the strangled host tree has rotted away. |

|

Some of the highlights we learned from the boards and Nick: IDIOT FRUIT (Idiospermum australiense) The most famous plant life found in the Daintree Rainforest that is well worth the mention is the idiot fruit. The Ribbonwood, commonly known as Idiot Fruit, is one of the rarest and most primitive of the flowering plants in the world, dating back 110 million years. Its discovery in 1970 was arguably Australia’s most significant botanical find, greatly increasing awareness of just how ancient these forests really are. These huge trees hold large brown fruits and the seed is highly poisonous, making this one of the few fruits that no rainforest bird or animal can tolerate. The tree’s only seed dispersal method is gravity. Therefore, distribution is limited. As a result, this plant occurs in very localised pockets of lowland tropical rainforest and around water catchment areas. KING FERNS (Angiopteris evecta) The King Fern is one of the largest and most ancient ferns in the world. These enormous ferns need constant moisture to help support their huge fronds, which can measure up to 5m on a fully mature specimen. Unfortunately, the King Fern is now only found in a few places in Australia due to a gradual drying of the continent. |

And Nick showed us how to stick your camera inside and point it up the structure. Photo Op! And Nick showed us how to stick your camera inside and point it up the structure. Photo Op! |

Button orchid. Dischidia nummularia.

Button orchid. Dischidia nummularia.

Not actually an orchid, the button orchid is in the Milkweed family.

This species is an epiphytic plant that is very commonly

seen growing on paperbark trees between Cairns and

Cape Tribulation. It grows along the bark, with tiny rootlets

that hold it in place, and will often hang down, like miniature

chandeliers, or strings of beads.

EPIPHYTES Epiphytes survive without roots in the ground. They also have the ability to trap nutrients and store their own water. Epiphytes are often supported by host plants. They can even grow so large they can no longer support their own weight, causing them to crash down to the forest floor. They come in various forms including Drynaria Rigidula, Bird’s Nest Fern, Basket Fern and Northern Elkhorn Fern. One of the most important epiphytes in this rainforest is the mighty Basket Fern. Ferns such as these can create their own ecosystems with many life forms using them as a home. Some frogs will even spend much of their life in the canopy, never reaching the ground.

NATIVE GINGERS (Family: Zingiberaceae) There are dozens of Ginger species found in North East Queensland and they are endemic to the region. These Daintree Rainforest plants are prized as ornamental plants and can be used in flower arrangements. Species such as the Native or Common Ginger (Alpinia caerulea) and the Snow Ginger (Alpinia arctiflora) also bear fruits that are favoured by the Cassowary.

FAN PALM (Licuala ramsayi) Palms have fan- or feather-like leaves, and their trunk girth does not grow with age. The spectacular fan palms are endemic to the lowland rainforests of Far North Queensland. They are slow growing and have strict requirements; a warm, shady position, with plenty of moisture. Swampy areas often become dominated by Fan Palm Gallery Forests, which shade out other light-loving species.

Red pediosporum. Claudia is great at miniatures. This flower bunch is (maybe) two inches across. Red pediosporum. Claudia is great at miniatures. This flower bunch is (maybe) two inches across. |

Boyd's forest dragons spend the majority of their time perched on the trunks of trees, usually at around head height, although daily movements can exceed 100 m (330 ft) on the ground. When approached, they will usually move around to the opposite side of the tree, keeping the trunk between them and their harasser. Boyd's forest dragons spend the majority of their time perched on the trunks of trees, usually at around head height, although daily movements can exceed 100 m (330 ft) on the ground. When approached, they will usually move around to the opposite side of the tree, keeping the trunk between them and their harasser. |

|

Tea and Ice Cream

Because tourists need to be fed and watered at least every two hours, the next stop was for refreshment: The Daintree Ice Cream Co, discretely tucked in behind several tea fields with their closely cropped bushes looking like a perfectly manicured boxwood hedge except that it was as wide as it was long. The ice cream store itself was a wooden shack with a roof that extended out to form a sort of car port, which protected guests from the sun or rain. A couple of tables were set out with three or four wooden chairs each, so one could sit and admire the fading display of spider lilies in the middle of the tight turning circle for cars.

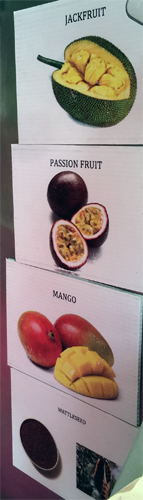

Samples of the fruits used to create today's offerings were laid out on a table near the serving window: jackfruit, passion fruit, mango, and wattleseed. Two rare, and two completely unheard of flavors. A special offer made it easy to make the right choice: "All four please." The jackfruit reminded me of a sort of lemony mango, and it had the same back-of-the-palate tickle that mango has, somehow making it feel like it would be easy to have a reaction to it. But I don't so it was delicious. The passion fruit and mango tasted like passion fruit and mango, two of my most favorites, and the wattleseed had a dark earthiness to it, strikingly unsweet, and a fabulous contrast to what normally passes as ice cream.

|

Instead of sitting I wandered around the small compound and found a tall set of shelves behind the shack that had a display of the fruits they grew for the icecream. I was disappointed to find the duran section was empty, because I would have loved to try that.  Spider lily (cararim lily) at tea plantation. Spider lily (cararim lily) at tea plantation.

|

|

"Public" boat ride

Last stop was a(nother) boat ride. We pulled in at a little gift-shoppy store sort of place, where as usual Nick was greeted enthusiastically. As usual despite how casual everything seemed, we were right on time to join a public tour. It wasn't a problem since we did not wait around for others to arrive, and nor was it crowded. But it couldn't have been a greater contrast with our excursion with Murray. Even I could see stuff we were missing, and when pointed some of them out most of the time to be charitable the answer was vague. They were able to find and point out the crocodiles which as always were a big hit. Best of show however was the black-necked stork which I was relieved that the guide was able to correctly identify.

|

The facts just kept coming. I tried to keep a list, but I probably missed more than I caught.

|

An excited young store clerk saw Nick and immediately rushed over to lead him to this surprise ... Which if I'm not mistaken is a green tree frog. No, really. An excited young store clerk saw Nick and immediately rushed over to lead him to this surprise ... Which if I'm not mistaken is a green tree frog. No, really. |

... another frog. But I'm not sure if its another green tree frog or something else? ... another frog. But I'm not sure if its another green tree frog or something else?

|

Things we learned from Nick: Hopi lasts 1,200-1,500 years, grows 1 metre every 100 years. Button orchid (not an orchid) on both cameras. We think we caught a glimpse of a feral pig, (brought in by the Dutch who arrived on the north coast some time before Cooke, according to Nick), and the ploughed up undergrowth he attributed to them certainly had all the hallmarks of a pig investigation. |

Green tree frog. Closeup Green tree frog. Closeup |

Black-necked Stork (male because of his brown eyes)

Black-necked Stork (male because of his brown eyes)

The Great Barrier Reef

Billed as one of the highlights of the trip, we were to spend two days Scuba diving on the Great Barrier Reef. By every Scuba diver's account, the be-all and end-all of Scuba locations, we even took lessons in a local pool to prepare ourselves to the max. Wet suits, snorkels, masks, and fins made up one-third of our luggage. We were two ocean dives short of Open Water certification when we left Boston. The boat and crew were perfect, just 9 divers, including a couple who were certified but had not been down in nearly 20 years. They were as happy as we were to be teamed up together for our refresher course. The two professional divers were Marty our instructor, and Brett, the quintessential bronzed, tossle-haired, Australian who turned out to be as talented as he was good-looking. A trained botanist and Master Diver, he also wielded a professional underwater camera.

Marty, Brett, and Peter. Peter's connection to Clare --more his style and the note came with a connection between Clare and Pete the diving boat captain)

We of course were early, so I had time to wander around the dock (no plans to board until the boat was actually pulling away). The early morning light was perfect.

It was blowing 20-25 knots, veering towards the maximum allowed, but off we went. For nearly two hours we crashed and heaved out to the reef, with me white-knuckle gripped to the back of the boat, eyeballs locked on the horizon. The rest of the team, including Claudia to my great relief, laughed joked and chatted behind me like they were relaxing in the lounge bar.

|

|

Predictably, despite the rough passage out, the trouble didn't really start until we stopped. Marty and Brett were truly fabulous. Completely clued in, they told the rest of the team that their top priority was to get me off the boat, and everyone nodded emphatic agreement. While I stayed locked on the horizon, they and Claudia dressed me in my skin suit, hoisted and adjusted the rest of my equipment and led me to the back of the boat. I held my mask to my face, assuming the required position, and stepped into the void. The water was cool and refreshing, but not as much of a relief as I was hoping. In 30 seconds Marty was suited up and in the water and immediately joined me. We went through the safety checks, making sure I could flood and clear my mask, and find my respirator again having thrown it way, then he motioned me to back off down the mooring line until I was about 5 feet under the boat.

It's a cool view there, looking up at the bottom of the boat, the prop shaft and the props themselves. I was just beginning to relax a little when I felt the tell-tale tightening of my stomach and 10 seconds later I just got the respirator out of my mouth before I barfed. Like a pro I found the respirator again, and now actually felt much better, so started to look around. Above me I could see the others enter the water one by one, go through the tests, and like birds on a wire we had to shuffle further down to make room for newcomers, but I could still see nothing below yet.

When we were all ready, we set off down the rope. Before long the bottom came into view, some 20-25 ft down. I was very happy with how well my ears were behaving, they were easy to clear, and buoyancy seemed well under control too. But the stillness was not providing the cure I was so hoping for. On the contrary, the lack of gravity, the weightlessness, was its own set of problems. Marty and Brett were incredible, making sure each of us got to see a giant clam closing when they touched it, dragging us to things they wanted us to touch, or bringing them to us (the sticky tenticles of a sea cucumer). Best of show was the Humphead Maori Wrasse that Brett had been feeding for months, so the fish actually recognized him, and came up to all of us, for all the world appearing to want to be petted, which we all did. Meanwhile Brett was photographing everyone, Marty made micro-adjustments to gear and buoyancy, and how they managed to herd us cats in this three-dimensional maze was a mystery. It was a full-time job for me trying to keep even one person in sight.

In addition to all the coral of course I may or may not have also seen (but C definitely saw) emporer angel fish, small travely or queen fish, pineapple cucumber, and best of show, Nemo the clown fish.

Finally it was time to ascend, and finally I lost it. Two or three more barf attacks on the way up, and two or three more back on the boat. It was obvious that I would not be able to go down again. The only consolation was that everyone else was fine. I hunkered down at the back of the boat, and everyone else partied. Lunch was served as we moved on to the next site. Like an old dog, everyone got used to just moving me to a different spot if I was in the way in my current one. They all went down again, and I dozed. Rinse and repeat. Even I could tell the sites were very different. The second one was a wall, and the third the coral came all the way to the surface. Only 90 minutes home, in somewhat calmer conditions, if only because we were going with the waves this time instead of against them. An eternity nevertheless. I'm glad I went, I wouldn't have missed it for the world, but the price was just too much to pay. I knew I would not be able to go out for the planned second day.

Claudia's experience I'm thrilled to report was very different. She was disappointed at how murky the water was (Pete, the captain, hadn't seen anything like it in 20 years) but everything else could not have gone better. She loved it.

Port Douglas

|

So Diving Day 2 took a whole different turn than planned. I really wanted not to go out again, but at the same time I could not be the reason that Claudi missed it. She reluctantly agreed to go without me. We wound down the mountain and as before pitched up at the marina just as the crew was assembling. There was a perfect mixture of disappointment and relief on the crew's faces as we explained the plan to leave me on shore. I hung around for a while as everyone prepped the boat and the other divers trickled in. I watched a school of tiny fish suddenly break the surface of the water and splash down again, sounding like a heavy rain shower, only two or three square yards wide. In fact it was the noise that first attracted me, and I stared at the water for several minutes until it happened again. They were so small you could barely see them, and only came out far enough to splash the surface, but it was a captivating display, and now that I knew what I was looking for, I could see the shoal as it drifted around underwater. They were no more than about an inch long and just like flocks of birds, they moved in unison. No one on the boat could tell me anything about them. Nothing. "Bait fish maybe?" "Probably avoiding predators?" "Yeah, I don't know what the predator might be." (I saw no sign of one, but that doesn't mean very much.) Pete suggested that I drive into town where a small park at the mouth of the river would give me a good view as they set out for open water. It did. As I waited, half a dozen cobalt blue welcome swallows dropped in to share the bollards I was using as a seat. Everybody waved as the dive boat puttered by, then almost as soon as it was passed me the bow lifted as it picked up the pace in the open water. Then they were gone. Sugar has been grown in this region since 1887 when it was introduced from Hawaii. Like the tea and bananas we'd also seen, I love these crops that help reinforce how foreign a geography I'm traveling through. When we had driven out towards the rain forest, we had passed a view of sugar canes and tulip trees that particularly caught my eye, and now I had plenty of time to kill, so I drove back out of town to look for it. This is always a challenge. If you don't see what you are looking for, how far do you go before you can be certain that you must have missed it? It could be just around the next bend. Finally the next bend became the outskirts of the next town and I conceded. Turning back around I returned to the spot where at least there was a tulip tree in bloom, and took a few shots out of principle, while the dog in the fenced-in yard behind yapped continuously, successfully keeping me from invading his home. I moved on, he returned to his porch, honor satisfied. I found several spots where the sugar cane wagons rusted next to the road. It was hard to tell whether they had been here for years, or whether the vines and grasses growing over them were just since the last season. Since they were right next to a ripening sugar crop, I prefer to assume that they would shortly be back in business. I moved around carefully, sticking to the shortest grass I could find. Every step I take in Australia where I can't see the ground I'm walking on I assume to be prime snake country. I stopped several times and took a bunch of pictures but again never found the one that said, "yup, got it". Finally mission-sort-of-accomplished, I drove back into town and parked in the underground lot Wendy had described. I was very happy to find a spot, meaning the car would not be out baking in the sun, or under the lorakeet gathering tree that left it liberally coated in poop, making it belatedly obvious why this prime spot had been left vacant. I took a slow stroll up the main drag. I found a bunch of souvenir shops of course. |

|

|

As I gained experience cruising through gift shops, of course I saw the same thing time and time again, and typically, sadly, the same crapola you see everywhere: shot glasses, key rings, snow globes. Baffling, but I guess people must collect them. One item that came up frequently at least had to be made locally, yet was equally baffling: kangaroo scrotums. I kid you not. Scrotum key fobs, bottle openers, even gear knobs for manual drive cars. Once I even saw a softer version, which I naively assumed to be a change purse but I later discovered on good authority was in fact a tobacco pouch, a purpose for which they (and many others like it apparently) were highly prized. In a dive shop I was delighted to overhear a conversation that unprompted laid the truth to the previously heresay budgie-smuggler reference which a previous customer had apparently come in to ask for. Excellent. I was intrigued to find a rack of didgeridoos in an upscale art store, from which the owner was determined to sell me something. They were nice, but nothing like as nice as the one I already had, and in addition to not being able to play them, he clearly did not know as much about them as he wanted to portray. When I told him that I'd already made my purchase at the excellent Didgeridoo Breathe in Freemantle, he became borderline hostile, and I was delighted to be able to walk away without him making a sale. Having now been up and down the street, it was finally time for the book-shop cafe that Wendy had insisted that I used to hang out. It was perfect. I found a small table at the back of the store where I could watch whatever was going on, then ordered a long black and my first savory muffin: cheese and onion. Wow. How come we don't have these at home? Americans must eat more muffins than the rest of the planet put together, but I've never seen a savory one. It took a while to serve, but it was steaming gently when it finally arrived, which helped me to ration it, but it was de-licious and did not sit around for long. I spent the next hour or two typing into the laptop, which was a wonderful luxury—being able to write up the events of the morning more or less in real time. But Murphy found that too tempting a target, and I could find no trace of the material when I got home.

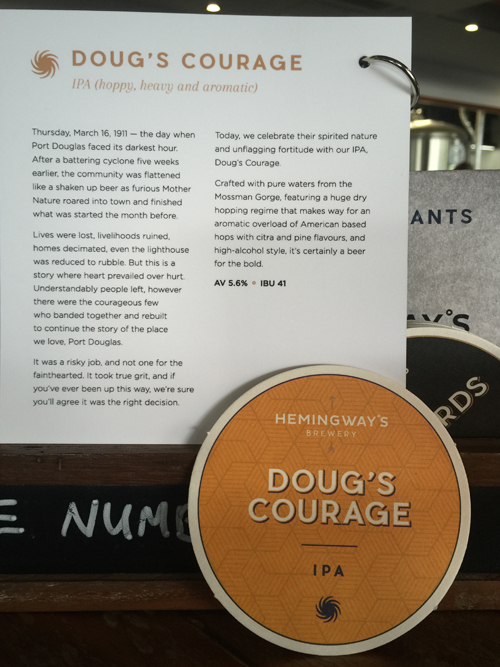

Around lunchtime I moved on to my final destination for the day: the Hemingway Brewery back at the river mouth. I had spotted it several times as we drove around, but had assumed I would not be able to get a chance to visit. It's an ill-wind ... I was nevertheless aware that a) I was on a very strict budget, b) it would not be smart to show up unfit to drive, so I resolved to make my two-drink limit last as long as I could. The bar was oddly placed along one side of a narrow shopping mall, but once I turned in to it I entered a completely different world. The other side of the pub let out onto the quay lined with boats, and the glass wall was basically collapsed so the boats were effectively part of the bar. I chatted up the barkeep who let me sample a few promising-looking options and picked

While I was sitting there I watched someone come in and order a growler, but not like any growler I'd ever seen before: it was a one litre can. The barman filled the open can like it was any other glass. It was a tin-stein rather than a tin-cup, and I suppose at just a litre, it was officially a crowler rather than a growler, so a tin-stein crowler was what I was watching. The keep placed a lid on it, put in onto a canning machine's turntable and in five seconds the machine had crimped the top on. An appropriate label was stuck on the side and it looked just like any other can. I gotta get me one of those. First another beer, I had a Hard Yards dark lager, then I ordered up my favorite to take home. I was amused to note that etched into the can lid was the usual 5 cent redemption info for the listed states. Usual except that this was Oz and these were still the instructions for US states. By now it was time to return to my spot at the harbor entrance to watch for the returning divers. In the nick of time. I hadn't been at my post for five minutes when they waved their way past. Mission accomplished I returned to the dock to greet everyone, say our final good-byes, and collect our certificates (worth nothing since we hadn't passed any tests), and we headed back to our little palace in the hills. |

|

The next morning it was time to pack up again, make our way back to Cairns and then on to Sidney. I think we would both have happily abandoned previous plans and retired right then and more importantly, there, living out our days in this little patch of heaven. So it was with mixed feelings that we packed up the car and said our good-byes with a final cup of coffee in Wendy's kitchen.

We passed a small pickup covered in flashing lights and a huge "Wide Load" sign. A perfectly common sight on US roads. And as we do in the US, we ignored it: it just means there's a little less room for you to do something stupid. At least we tried to ignore it: everyone else in our line of traffic swerved to the curb, and to avoid the risk of grazing the side of the car with the walls and trees that came right up the tarmac, came to a dead stop. Therefore we were obliged to do the same, and a good job too, because a second later the wide load came around the corner and it was H U G E. Without the warning we would have been smeared against the wall (there to prevent us from being shoved into the ocean) like so much peanut butter on a slice of toast.