Brekumansu |

|

Finally, around 2:30pm we pull up outside Alexis's bungalow in Brekumansu. We unload the car, and count out the 600-700 Ghc (in 10s remember) that we owe Emanuel. He finally admits that he'd been nursing the car all the way home—he'd developed shock absorber problems on the way up to Mole, and hoped he'd be able to make it home without letting us down. We had noticed some odd noises, but assumed his careful driving was for our benefit not the car's.

One of the first things you notice in the village is that everybody lives outside. Everyone also needs to be greeted. "Fine evening." Progress is therefore quite slow, especially on our first foray to find our host Ntow's compound. The women all move as if they have their bowls on their heads, even when they don't.

Living outside certainly confirms what we've seen as we've travelled around, but now wandering the village the evidence comes sharply into focus. Kitchens are three rocks in front of the house, on which the women balance a pot, and between which a small fire is carefully tended.

The two-room house belonging to our host Ntow (concrete, unlike most of the mud huts in the village) is home to six and the teenage daughter has one room to herself, leaving the other five to share the second room. We were never invited inside but we never have a reason to be. One day a door was ajar, and I glanced inside. The bed took up more than half the space, and was built like a long-drop, with tree branches forming the slats and a piece of four-inch thick latex foam covering most of the top. I was not expecting blankets but there were no sheets or pillows either. Sister Patience had been making soap, and the majority of the floor space was taken up with the fist-sized balls lined up in rows drying out.

Our hosts Ntow and Sister Patience, and their smalls Leticia, Gideon, Benjamin, Deborah and Ebenezer live about 50 yards from a primary side road in one of the larger compounds. It is not the size of the compound but the industry which immediately draws your attention. A corrugated roof covers an area about 15 feet by 30. Under it, we're thrilled to find two small engines chugging noisily. They were broken down when Wayne was there the year before, and Ntow appeared to have no way to afford any repairs. One engine drove a flour mill, which was being used to grind maize. Goats and chickens hung around nibbling at the flour regardless of whether it was in the catchment bin or on the floor. The other was shredding palm nuts. Several old oil drums were standing over fires cooking up the raw palm nuts to soften them. Then the engine shredded them to produce a spongy mass that could be shovelled into a press (just like a cider press) where two women wound down the pressure plate to squeeze out the precious oil. Ntwo accepts maize and palm nuts to process for his neighbors, and tithes a portion of the product as a fee. He (and his workers) run the machines, and can achieve in about five minutes what would have taken the neighbor several days by hand. Incredibly, after the pressing they are not done. Women and children then pick through the remains because each of the nuts contained a kernel—another nut—which is a source of oil in its own right. In fact palm nut kernel oil is a standard ingredient in many of our manufactured foodstuffs, and was in the first candy bar I ate on the plane home. The is more on palmnut oil and photographs of the process in the encyclopedia section.

Our hosts Ntow and Sister Patience, and their smalls Leticia, Gideon, Benjamin, Deborah and Ebenezer live about 50 yards from a primary side road in one of the larger compounds. It is not the size of the compound but the industry which immediately draws your attention. A corrugated roof covers an area about 15 feet by 30. Under it, we're thrilled to find two small engines chugging noisily. They were broken down when Wayne was there the year before, and Ntow appeared to have no way to afford any repairs. One engine drove a flour mill, which was being used to grind maize. Goats and chickens hung around nibbling at the flour regardless of whether it was in the catchment bin or on the floor. The other was shredding palm nuts. Several old oil drums were standing over fires cooking up the raw palm nuts to soften them. Then the engine shredded them to produce a spongy mass that could be shovelled into a press (just like a cider press) where two women wound down the pressure plate to squeeze out the precious oil. Ntwo accepts maize and palm nuts to process for his neighbors, and tithes a portion of the product as a fee. He (and his workers) run the machines, and can achieve in about five minutes what would have taken the neighbor several days by hand. Incredibly, after the pressing they are not done. Women and children then pick through the remains because each of the nuts contained a kernel—another nut—which is a source of oil in its own right. In fact palm nut kernel oil is a standard ingredient in many of our manufactured foodstuffs, and was in the first candy bar I ate on the plane home. The is more on palmnut oil and photographs of the process in the encyclopedia section.

There is one small table and a couple of benches in the yard, and these are gathered together for Ntow and the obrunis to eat at. Sister Patience and the smalls eat from their laps, sitting on the step to the house, or whereever else they can perch. It is painfully clear that we get fed first and they get what is left. It is therefore extremely bad form to leave anything, and when I just can't finish my portion one night, Alexis slips the remains to one of the kids, who has no problem polishing it off. I'm relieved to find that Alexis and Ntow also have trouble, and often slip morsels to the dogs, whom needless to say are not far from the table. But apart from this table, and another even smaller one that Sister Patience has just outside her kitchen.

There is one small table and a couple of benches in the yard, and these are gathered together for Ntow and the obrunis to eat at. Sister Patience and the smalls eat from their laps, sitting on the step to the house, or whereever else they can perch. It is painfully clear that we get fed first and they get what is left. It is therefore extremely bad form to leave anything, and when I just can't finish my portion one night, Alexis slips the remains to one of the kids, who has no problem polishing it off. I'm relieved to find that Alexis and Ntow also have trouble, and often slip morsels to the dogs, whom needless to say are not far from the table. But apart from this table, and another even smaller one that Sister Patience has just outside her kitchen.

She actually has a small hut built around her stove, which is the traditional three stones supporting a cauldron, and a wood fire burning between the stones. If it is 95°F outside, it must be 120°F inside. There are none of the chairs, cupboards, utensils, or prep boards we take for granted in our kitchens to say nothing of all the other rooms and furnishings.

She actually has a small hut built around her stove, which is the traditional three stones supporting a cauldron, and a wood fire burning between the stones. If it is 95°F outside, it must be 120°F inside. There are none of the chairs, cupboards, utensils, or prep boards we take for granted in our kitchens to say nothing of all the other rooms and furnishings.

The machete is the tool of choice, and it is used for everything: rooting out cassava, planting maize, opening coconuts, skinning oranges, and even I noticed one evening, cleaning Ntow's fingernails. Even primary school kids can be seen wandering to school whacking at the undergrowth with their machetes, which since they don't come in kid sizes, reach their ankles and in a couple of cases I saw the small was short enough to be able to drag the blade along the ground. I watch Leticia chop okra by holding it in one hand (her right of course) while she cross-hatched the end of the pod, then cut off a quarter-inch slice, and then repeated the process over and over to dice the okra. The juice ran down her legs. It took 40 minutes to perform a task that would take five with a chopping board.

The local seamstress Latysha has her sewing machine and iron set out on a couple of small tables under an awning right on the side of the road. She always seemed to be there whenever we walked past. But it was also a favorite hangout, and several other women and girls were generally there with her. We often stopped to chat.

The local seamstress Latysha has her sewing machine and iron set out on a couple of small tables under an awning right on the side of the road. She always seemed to be there whenever we walked past. But it was also a favorite hangout, and several other women and girls were generally there with her. We often stopped to chat.

Latysha makes all the school uniforms. It suddenly occurs to me that this is an inevitable consequence of the infrastructure (or rather the lack thereof).

The local market, just like ours, has lots of western-style clothes at discount prices. And like some of ours, these are job lots of random styles, colors and patterns. Unlike ours, this is the high end of the market. The cheaper places are selling second-hand examples. Meanwhile, in much of Ghana there do not seem to be "stores" where you can predictably buy a specific color time after time and year after year, as you would need for a uniform. So as in days of old, bolts of cloth are procured, and the local seamstress makes each uniform up to order. She also seems to make the more traditional style clothing for women (men have to go to the tailor).

If you can persuade someone to let you take their photograph (and finally this is pretty easy) you can win the subject over completely by showing him or her the preview on the back of the camera. Suddenly they want six more. "Now take one like this. Now take one with my friend. Now take one of my friend on her own. Now take one of me without my hat. No I wasn't ready, take that one again. Now let me see..." and so on. Latysha allowed me to take several pictures before she says "Measter Reechard, you need to take me to America." She's a good looking woman, but I have to tell that she "would not want to be wife number two to wife number one." She does not bring the subject up again. Another day, after the crowd demanded another session of photographing and showing them the result, one of the girls cleaned, quartered and fried some yams for us on the spot—very tasty, and one of our favorites, not least of course, because the boiling oil made them safe to eat.

If you can persuade someone to let you take their photograph (and finally this is pretty easy) you can win the subject over completely by showing him or her the preview on the back of the camera. Suddenly they want six more. "Now take one like this. Now take one with my friend. Now take one of my friend on her own. Now take one of me without my hat. No I wasn't ready, take that one again. Now let me see..." and so on. Latysha allowed me to take several pictures before she says "Measter Reechard, you need to take me to America." She's a good looking woman, but I have to tell that she "would not want to be wife number two to wife number one." She does not bring the subject up again. Another day, after the crowd demanded another session of photographing and showing them the result, one of the girls cleaned, quartered and fried some yams for us on the spot—very tasty, and one of our favorites, not least of course, because the boiling oil made them safe to eat.

After supper, and as it is getting seriously dark, the kids are sent with us to see us safely home, and they fight over who can carry what—then they walk back home alone. Also, Leticia the high-schooler has about 20 gallons of water in the basin balanced on her head. Like the pito woman, it is so much weight that she can't lower it on her own. There's a panic when we get home, as we rush around to find a flashlight while she just stands there, waiting until we can shine a light into the barrel for her to aim at. Of course she doesn't miss with a drop, but she's notably relieved (some might say irritated) when she's finally able to tip her burden into the appointed spot. Leticia is the only Ghanaian who I never see smiling. Not once.

After supper, and as it is getting seriously dark, the kids are sent with us to see us safely home, and they fight over who can carry what—then they walk back home alone. Also, Leticia the high-schooler has about 20 gallons of water in the basin balanced on her head. Like the pito woman, it is so much weight that she can't lower it on her own. There's a panic when we get home, as we rush around to find a flashlight while she just stands there, waiting until we can shine a light into the barrel for her to aim at. Of course she doesn't miss with a drop, but she's notably relieved (some might say irritated) when she's finally able to tip her burden into the appointed spot. Leticia is the only Ghanaian who I never see smiling. Not once.

It turns out that in addition to doing our laundry (and much of our cooking), she's responsible for every drop of water in the house. She carries every gallon about 400 yards, and now there are three of us using it. It is a crushing realization. I make sure that the only water I use is a small bucketful for an outdoor shower (most) nights. Wayne the outdoorsman had built the shower during his first visit: "I always very much enjoyed the experience of cooling down and cleaning up while standing buck-naked under the stars, listening to the nights sounds." The only other water I need is for morning coffee, teeth brushing and meds-swallowing, and we use bottled water for that, which we porter in ourselves.

The next day we set up our new morning routine: we left the house at around 5:45AM to be out in the bush as dawn woke the birds. The trips varied from a couple of hours to four or five, and sometimes we'd stand in one place for an hour, sometimes covering considerable ground. On one of the longer treks between the village and the mountains, we someone coming the other way, who claimed that we were on his land and therefore should pay him for our visit. We decided we'd gone far enough.

The next day we set up our new morning routine: we left the house at around 5:45AM to be out in the bush as dawn woke the birds. The trips varied from a couple of hours to four or five, and sometimes we'd stand in one place for an hour, sometimes covering considerable ground. On one of the longer treks between the village and the mountains, we someone coming the other way, who claimed that we were on his land and therefore should pay him for our visit. We decided we'd gone far enough.

We came across several settlements in our travels. One, a compound, appeared to be Ntow's deserted old village. Although it showed little sign of life, the remains of a fire smoldered in the middle of the yard. Another was definately derelict, and just a single house. A third, in extremely good condition but similarly devoid of life, barring a rooster and his flock, was one of the most photogenic spots we discovered in our entire trip. After short trips, Alexis made us coffee. Otherwise it was then time to see what Ntow had organized for us.

A morning at farm

One morning Ntow took us out to farm. As Wayne observed, Ntow always says "go to farm," where "farm" is a noun. Not "the farm" or "my farm," just "farm." Everybody went, and the smalls carried the bags. Since there were not enough bags to go around, Alexis gave Debora a water bottle to carry, which she spent much of the trip trying to balance on her head. That day they were planting maize in a patch of ground that had been more or less cleared of other vegetation. Two maize kernels and a little pellet of animal deterrent were dropped into each hole. The holes were one pace apart, and of course were dug by shoving the tip of the machete blade into the ground. The flat of the blade then patted the ground down again, and the sower took another stride and did it again. Ntow used his machete to pry some of the bigger tussocks of grass out of the ground. But once he'd exposed the roots, he just rolled the root ball over into the sun and left it there to dry out and die. Meanwhile the smalls sat under a large bush with Alexis, and turned the water jugs and a couple of sticks into a remarkably able percussion band.

It seems that they make almost no attempt to "weed" so once a crop was planted, it was left to fend for itself. It took a while therefore to spot the difference between bush and farm. But the sudden appearance of a reasonably square patch of cassava, say, was definately a sign. But the corner that Ntow took us to had been nearly completely cleared, giving me very much the idea that he was just searching the hedgerows as it were when he suddenly stopped, stabbed at the ground a few times with his machete, and then used it like a spade to pop some cassava tubers to the surface. He did this a few times, and in five minutes had collected enough for supper. Again, this was a very brief glance, and life in general might be very different when they were not entertaining guests, but this experience left me with the impression that each day they spent about an hour sowing, about ten minutes reaping and then they were pretty much done.

It seems that they make almost no attempt to "weed" so once a crop was planted, it was left to fend for itself. It took a while therefore to spot the difference between bush and farm. But the sudden appearance of a reasonably square patch of cassava, say, was definately a sign. But the corner that Ntow took us to had been nearly completely cleared, giving me very much the idea that he was just searching the hedgerows as it were when he suddenly stopped, stabbed at the ground a few times with his machete, and then used it like a spade to pop some cassava tubers to the surface. He did this a few times, and in five minutes had collected enough for supper. Again, this was a very brief glance, and life in general might be very different when they were not entertaining guests, but this experience left me with the impression that each day they spent about an hour sowing, about ten minutes reaping and then they were pretty much done.

Of course Ntow had his business ventures back in the village, and Sister Patience would spend several hours turning the harvest into supper, but this was no eighteen hour day they were working.

As the days went by, Wayne and I often met people on the paths who seemed to have similarly gathered an armful of produce which they then took home, or to the road, where we had seem hundreds, thousands of examples of people sitting waiting for a passerby to purchase their daily needs. I asked Ntow how long things took to grow. He seemed a little vague, but he thought cassava grows in 12 months, (surely accurate) palm nuts take 5 years, but the palm from which they take the sap for akpeteshie takes 15 to 20 years to get to the harvest point.

Coconut palms seem to vary in height considerably, but they all present a single straight or curved trunk with a froth of leaves right at the very top. The coconuts nestle at the base of the leaves forming a sort of necklace around the trunk. The coconut palms around the village and farm are no different, but are far taller than I remember, Wayne and I estimated they were at least 40 feet tall. The volunteer who shinned up the trunk trailing his machete made it look like he might have been climbing the stairs to bed. Once he arrived at the crown, and pulled himself out and around that coconut and leaf barrier he started to harvest the coconuts, but he sliced open the first two or three for himself, drained them of their milk and then threw the nuts overboard. For the next five minutes he then maneuvered himself around the leaves and hacked off all the mature fruit. Finally his machete came sailing down and buried itself in the undergrowth. When he was done, he lowered himself back over the rim, grabbed the trunk between the arches of his feet, and slide back down the ground.

Coconut palms seem to vary in height considerably, but they all present a single straight or curved trunk with a froth of leaves right at the very top. The coconuts nestle at the base of the leaves forming a sort of necklace around the trunk. The coconut palms around the village and farm are no different, but are far taller than I remember, Wayne and I estimated they were at least 40 feet tall. The volunteer who shinned up the trunk trailing his machete made it look like he might have been climbing the stairs to bed. Once he arrived at the crown, and pulled himself out and around that coconut and leaf barrier he started to harvest the coconuts, but he sliced open the first two or three for himself, drained them of their milk and then threw the nuts overboard. For the next five minutes he then maneuvered himself around the leaves and hacked off all the mature fruit. Finally his machete came sailing down and buried itself in the undergrowth. When he was done, he lowered himself back over the rim, grabbed the trunk between the arches of his feet, and slide back down the ground.

The climber and Ntow then set about dressing the nuts. First they cut a few slices of husk off the top until the nut was exposed, then they cut a small piece off the top of the nut, just like preparing a hard-boiled egg. We were handed coconut after coconut to drink the milk straight from them. Ntow helped the smalls to drink from theirs. We each handed back the empty nut. This he held in the palm of one hand, and with terrifying precision used his other hand to give it a terrific whack with the machete, cracking the nut from north to south. He spun the nut in his hand, so that the opposite side was uppermost, and gave this side a similar whack. Each time, in just two blows, and without ever losing a hand, each nut was cleaved in two.

A last slice of husk was carved off, and the slice and the two halves handed back. The little slice formed a sharp-edged spatula, perfectly shaped to scoop and scour the soft white flesh out of the inside of the coconut. It was quite unlike any coconut I'd ever had before. Closer to the consistency of squid than the desiccated sawdust I am used to. Wayne believes this had as much to to do with the flesh being immature as it did the freshness. Given how thin the layer was compared to the mature fruit we are used to, this makes a lot of sense. The two men just kept serving them up until everyone refused to take another. Then they prepared the remaining nuts by cutting the majority of the husk off, but leaving them closed. That way the minimum material was carried back to the village. On the way home, some women collecting oranges insisted we came over and talk to them. Then they insisted we take some oranges with us.

A last slice of husk was carved off, and the slice and the two halves handed back. The little slice formed a sharp-edged spatula, perfectly shaped to scoop and scour the soft white flesh out of the inside of the coconut. It was quite unlike any coconut I'd ever had before. Closer to the consistency of squid than the desiccated sawdust I am used to. Wayne believes this had as much to to do with the flesh being immature as it did the freshness. Given how thin the layer was compared to the mature fruit we are used to, this makes a lot of sense. The two men just kept serving them up until everyone refused to take another. Then they prepared the remaining nuts by cutting the majority of the husk off, but leaving them closed. That way the minimum material was carried back to the village. On the way home, some women collecting oranges insisted we came over and talk to them. Then they insisted we take some oranges with us.

We're nearing the end of the trip, we're getting used to the heat, we've already achieved all the objectives we set for ourselves, it's clear sailing, we're in the home straight, but something is still gnawing at me, keeping me on edge. It is quite clear that neither Wayne nor Alexis are afflicted by it, and even now I can't figure out what I could not let go of. There were undoubtedly major challenges here. Perhaps it was being constantly on ones guard about the water—a momentary lapse putting your toothbrush under a faucet (when there was one) which is such an instinctive reaction, constantly needing to find a source of Voltic, only being able to use your right hand for salutation and eating—not a natural thing for me—not being able to trust food sources, or risking being served something one could not stomach. There was something claustrophobic about it—treading the narrow path of safe sanitation.

Perhaps it was the daylight thing. We were always out before dawn, and back after dark, so I never spent any time in the house when I could see what I was doing, so I never felt organized. Everything I needed always seemed to be right at the bottom of my pack, there was no room to repack it, no light to see by, and so a constant challenge to try to keep things in a consistent enough place that they could be found in the dark. Can't put my finger on it. It was irrational, because we were never in any danger, both Wayne and Alexis are experienced travellers, we had each others backs, and the bottom line is we were having an absolutely amazing time. It was truly a privilege to be among these people and their hospitality was overwhelming. I don't get it.

An afternoon at the akpeteshie plant

Wayne's Ghana Guide (Bill's Little Brother) provides an excellent account of akpeteshie making which is reproduced almost in its entirety in the reference section, along with a more complete photographic record.

We walked out to Ntow's brother's still which is in the middle of a field of downed palm trees. Since it consists of half a dozen plastic 55-gallon containers fermenting the palm wine, the two 55-gallon steel drums forming the still, a small pile of firewood and the thatched roof providing shade for the whole operation, it feels like a fairly simple operation to keep moving the processing plant into the middle of the current "harvest." The still is gently cooking a batch of palm wine over the fire, and then a copper tube carries the evaporates over to the condenser where the copper coils down through the second drum which is full of water. A far-cry from the monk's stainless steel work of art. At the bottom, the outlet is allowing a constant trickle of liquid into a small plastic jug.

We spend an excellent hour touring the facility, trying the palm wine (very sweet), and having the whole process demonstrated. Ntow's brother is extremely proud of the quality of his product, explaining how they only sell the middle "sweet" portion of the distillate (the ends being poisonous or weak, both of which one should obviously avoid purchasing). I have to say that although we are clearly not experts, there was no question that this was the best akpeteshie we drank in Ghana, which makes it the best in the world. We made it clear that we needed to buy some significant quantities, and Ntow promised to arrange it. Although there was not going to be any negotiation about the price, it was still reasonably complicated: the following day Ntow asked how much we were thinking of and we handed him two empty 1.5L Voltic bottles; the day after that the bottles reappeared filled to the brim. 1Ghc each.

Spots

Being in one place for a few days especially as guests of such a prominent local citizen gave us more latitude to hang out and explore. So it did not take us long to come across and agree to explore our first spot since Yeji. Instantly recognizable by it's blue and white striped exterior, I realized that we'd seen these all over the place, even in the poorest smallest villages. The two we frequented in Brek had much the same format, and I'm sure they all did. Although like any pub, the size, furnishings and clientele varied hugely, the common denominator was a large, locked, cabinet at the back of the room. At first glance it looked more like a rabbit hutch, but closer inspection revealed the inhabitants to be bottles of liquor, some with labels some without.

On our first visit, and this being mid-afternoon, we played our cards close to our chests and only ordered beer. Warm of course. In fact this became our beer place. Much more interesting than the beer were our fellow drinkers, some of whom had gotten a considerable head start. There must have been about half a dozen other patrons. As always in Ghana, the bar keep (a woman, of course) and a guy who seemed to be connected to her were perfectly civil with us, and even protective of us. The majority of the other patrons were clearly thrilled that we stopped by. But one particularly wobbly denizen was not. It was not that he objected, but he became increasingly agitated when the help tried to prevent him from giving us his important message for an eleventh time. It was not important enough for me to remember, other than the rather alarming claim that he had something to do with the teaching profession. Indeed, Wayne later confirmed that he had met him along the road past Ntow's compound during his previous visit, and he had mentioned then that he taught up in Kwaku Sae. He was physically ejected once, but he came back a few minutes later. There was a lively discussion amongst the patrons. Of course we could not understand a word because they were speaking in the local dialect. But what the body language came down to seemed to be a moral dilemma. Although we were not to blame, we were causing a disturbance. Would they ask us to leave? We did not hurry our beers, but nor did we order another one.

The other spot we used in Brek was Ntow's "local" and there, under his guidance, we were much more adventurous. We love akpeteshie, and they loved the fact that we loved it. I can't believe how much of it we drank. Unlike the pito, one sniff of the akpeteshie is enough to make your nostrils stand to attention and salute. Although Wayne's etiquette lessons included a lecture on not sniffing food or drink, you can't help it here. The fumes grab your face and drag your nose into the glass. The crowd thinks it is hysterical as you resurface teary-eyed.

Nevertheless it rapidly became our habit to have a pre-dinner aperitif at the spot. And we always had two shots. Wayne and I both took one look at the shot measure and knew immediately that this was a perfect souvenir if we could find one. The bowl of this ladle-like affair was a glass, although it was more of a mini-tumbler than a shot glass. But what attracted us was the handle which was fashioned from a fork with the tines bend up and down to clasp the tumbler firmly so that the server's hands were clearly nowhere near your drink, even if the liquor overflowed (which of course, especially with Ntow serving, it did regularly). Wayne took pictures. We found the souvenirs at a market in Koforidua, so we bought lots of them, and now we're home the evidence is clear to all that the glass is indeed large, and the akpeteshie is strong. The bravest of all the folks who've tried it (and that is a lot of people) haven't gotten through so much as half a measure. While your nostrils are saluting, the rest of your system is duly respectful and warns you off going much further.

Kwaku Sae

Kwaku Sae

It is a hot and humid afternoon. Now there is a surprise. But a mile or two back from Brek

on the road past Ntow's compound

is another small village, and behind that, fifteen minutes up a steep path into the hills is an even smaller village, which boasts a swimming hole. I guess the good news is that the climb is on the way up and not on the way back. When we get to Kwaku Sae Ntow bids us sit under an awning where a couple of chairs are laid out, while he disappears to pay his respects, and rustle up a guide so we can visit the ecotourism attractions recently set up in the village: snail and grasscutter rearing, and a mushroom farm. (No, I'm not kidding.)

It is a hot and humid afternoon. Now there is a surprise. But a mile or two back from Brek

on the road past Ntow's compound

is another small village, and behind that, fifteen minutes up a steep path into the hills is an even smaller village, which boasts a swimming hole. I guess the good news is that the climb is on the way up and not on the way back. When we get to Kwaku Sae Ntow bids us sit under an awning where a couple of chairs are laid out, while he disappears to pay his respects, and rustle up a guide so we can visit the ecotourism attractions recently set up in the village: snail and grasscutter rearing, and a mushroom farm. (No, I'm not kidding.)

A girl dolled up in her Sunday best stood and stared at us for a while. It must be Sunday. We stared back. Her dress was as shockingly pink as it was clean. How could it be kept that way amid the dust and grime of Monday through Saturday?

Collecting the guide takes longer than touring the attractions. The grasscutters are a 15lb rat, and they live in cages about the size of a rabbit hutch. They sit around in the cage waiting to mate, or waiting to give birth, or eating, or some combination of these. After a minute of looking at the cages, we're done. The snails have even less infrastructure. A wooden frame about 6ft square is laid out on the ground in the shade and has a chicken-wire lid. Through the lid it is clear that the box encloses a piece of ground littered with leaves, exactly like the surrounding area. The guide unlocks the lid and moves aside some of the larger leaves, to reveal the snails. I can't deny that they are impressive. They look like regular garden snails, but the shells are probably three or four inches across. We've seen piles of them for sale on the roadside, offered to us through the window of the bus or tro-tro, and at the market. But interestingly, we've never been offered any to actually eat. Perhaps we got lucky. I've certainly eaten snails many times, but they've always been small morsels serving as garlic vehicles. This would have been an entirely different problem. Lots of questions came to mind though—are they hard to find in the bush? (Wayne says no, but they are mostly active at night which may be fairly unappealing.) Are they good to eat or just available? (Wayne says delicious!) Are they easy to breed? If they are a regular part of the diet, and it is this easy to cultivate them why doesn't every village have one, and why hasn't this been done since time immemorial?

Finally the mushroom farm was a much grander affair, and really rather elegant. I liked the building, and the orderly rows of pots waiting for mushrooms. But if there were 1000 pots (which is probably an underestimate) there were only three or four mushrooms, one of which they gladly picked to show us. Again, a long series of questions about how and when to see a return on investment sprang to mind, but this was not the time or place to ask, so I did not. Time for a swim.

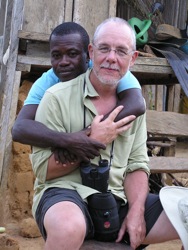

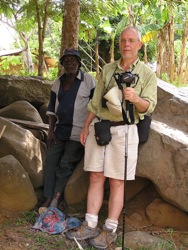

Ntow is nowhere to be seen, but no matter because I can't imagine him wanting to be in the swimming party. So we head off up the hill again. When we get to the second village, the first thing to do is to seek out the village chief, and get his blessing. He's easy to find (it is not a large village) and he's out sitting under the shade of a large tree in the center of the village. He looks about 150 years old. Apparently he is very taken by us, or perhaps I should say by me in particular, because he removes his hat to reveal a scrabble of grey hair, which by gesticulating he makes clear that he likens to my own (I having already removed my hat out of respect). Alexis explains that since Africans don't typically go grey until they are much later in life compared to caucasians, and old age is also more closely associated with wisdom, he (and doubtless most of his countrymen) interpret my grey hair not just with great wisdom, but also advanced old age. I'm not quite sure how to take this news, which is at once flattering and insulting, but on reflection I figure if the chief regards me as a peer, no disrespect was intended, and overall this was a good position to be in. Hmm. Perhaps that is why many people called me "Mister Richard." Several photographs are taken of this momentous meeting, and we are blessed to use the swimming hole.

Ntow is nowhere to be seen, but no matter because I can't imagine him wanting to be in the swimming party. So we head off up the hill again. When we get to the second village, the first thing to do is to seek out the village chief, and get his blessing. He's easy to find (it is not a large village) and he's out sitting under the shade of a large tree in the center of the village. He looks about 150 years old. Apparently he is very taken by us, or perhaps I should say by me in particular, because he removes his hat to reveal a scrabble of grey hair, which by gesticulating he makes clear that he likens to my own (I having already removed my hat out of respect). Alexis explains that since Africans don't typically go grey until they are much later in life compared to caucasians, and old age is also more closely associated with wisdom, he (and doubtless most of his countrymen) interpret my grey hair not just with great wisdom, but also advanced old age. I'm not quite sure how to take this news, which is at once flattering and insulting, but on reflection I figure if the chief regards me as a peer, no disrespect was intended, and overall this was a good position to be in. Hmm. Perhaps that is why many people called me "Mister Richard." Several photographs are taken of this momentous meeting, and we are blessed to use the swimming hole.

The village emptied of smalls as we made our way up and out of the village, or at least it felt that way as our numbers swelled from three and a dog to nearly two dozen. We did not lose many of the audience either in the fairly long and arduous climb, though I suppose it was not nearly so long or arduous to them. It was a beautiful and coolly shaded spot, and apart from the ambient temperature, and more especially the ambient temperature of the water, it felt much like a New England dell and mountain stream. With the audience stacked up along the steep sides, it was quite a challenge to find somewhere to change into our swimwear, or if wearing it, to change back into something dry afterwards.

The smalls all came to watch, not to swim. That's because they cannot swim themselves. Let's face it, most Ghanaians would be hard-pressed to find enough water in which to immerse themselves, and even if these particular villagers wanted to use the bounty afforded them, the deep water and steep vertical sides would make learning an extremely daunting process. No surprise then that most were extremely cautious about getting too close, nor that they would be absolutely fascinated by the ability of these great white whales to swim and float with such apparent ease. Willa the dog was another story, and she soon got bored and made the several mile trip back to Brekumansu long before we did. The smalls had no such reservations at the waterfall, which was the last stop and where they took crazy risks climbing over through and around the near-vertical slope catching freshwater crabs. There was not enough water to drown in, but plenty enough slippery rock to provide neck-breaking falls.

Asamankese

It's been several days since I switched to my camera's backup battery, and the idea of the camera dying is not acceptable, but with no power, what to do? Meanwhile, Alexis has the same issue with her cell phone (no wonder, given how much time she spends on it). But apparently there is an easy solution, and furthermore it gives us another opportunity to use the tro-tros, which is a heightened attraction since we recently agreed to hire a taxi to take us to Accra thus eliminating them from that trip. As if by a miracle, the solution also requires us to buy beer at a spot in Asamankese, the local market town. What's not to like? And for once we have the luxury of travelling without baggage.

So we walk the 50 feet to the road, wait 10 minutes and the first tro-tro stops and picks us up. Why is this so bad? Why do we all need our individual horseless carriages, if by no one having one, public transport can run at regular intervals down every street in the county? No parking hassles at the other end, and no worrying about one beer or two either. Fifteen minutes later everybody piles out in the center of Asamankese. First stop, naturally, is the spot. It is tiny, with just one table outside. Alexis takes my camera battery and charger and her phone, and disappears inside, while Wayne and I sit and gaze at the passers-by, most of whom gaze right back. This street, as we now know so well, has a deep, wide, rain-water gutter running down the side, which the spot has bridged and parked our table over. Alexis apparently fell into one of these one night, and looking down into the vertical-sided three foot drop, and the garbage and worse at the bottom being kept moist by a trickle of water running through it, gave a vividly more dramatic dimension to the "I fell in a ditch" story. It's easy to imagine dying from shock and panic, never mind from the fatal illnesses one might have collected.

So we walk the 50 feet to the road, wait 10 minutes and the first tro-tro stops and picks us up. Why is this so bad? Why do we all need our individual horseless carriages, if by no one having one, public transport can run at regular intervals down every street in the county? No parking hassles at the other end, and no worrying about one beer or two either. Fifteen minutes later everybody piles out in the center of Asamankese. First stop, naturally, is the spot. It is tiny, with just one table outside. Alexis takes my camera battery and charger and her phone, and disappears inside, while Wayne and I sit and gaze at the passers-by, most of whom gaze right back. This street, as we now know so well, has a deep, wide, rain-water gutter running down the side, which the spot has bridged and parked our table over. Alexis apparently fell into one of these one night, and looking down into the vertical-sided three foot drop, and the garbage and worse at the bottom being kept moist by a trickle of water running through it, gave a vividly more dramatic dimension to the "I fell in a ditch" story. It's easy to imagine dying from shock and panic, never mind from the fatal illnesses one might have collected.

Alexis reappears with three beers and no electronics. They could have been, should have been, making a beer commercial. Two dusty, grubby guys, several days/weeks from their last shave, sit at a dusty, grubby table in the afternoon light of another crazy hot cloudless day. They stare vacantly at the bottles placed on the table in front of them as their companion pries the caps off. All you can hear is the boys licking their lips, and the oh-so sweet phist of the pressure being released from the beer. Already the condensation is beading up on the outside of the bottles (yes, these are cold ones). The camera focuses in on the eyes of one of the drinkers, and we see the tension dissolve and replaced by sheer contentment. All is well with the world. Fade to black.

Alexis reappears with three beers and no electronics. They could have been, should have been, making a beer commercial. Two dusty, grubby guys, several days/weeks from their last shave, sit at a dusty, grubby table in the afternoon light of another crazy hot cloudless day. They stare vacantly at the bottles placed on the table in front of them as their companion pries the caps off. All you can hear is the boys licking their lips, and the oh-so sweet phist of the pressure being released from the beer. Already the condensation is beading up on the outside of the bottles (yes, these are cold ones). The camera focuses in on the eyes of one of the drinkers, and we see the tension dissolve and replaced by sheer contentment. All is well with the world. Fade to black.

We have at least an hour to kill before we can retrieve the toys, so when the bottles are finally drained we head for the market. There is no paperwork, there is no charge, and there is no doubt that the toys will be present and correct when we return. Pause to reflect how this situation might be handled in "more civilized?" countries.

At the market we try to get the parts we need to make our shot server souvenirs, and as a back-up buy some parts that are close. We look for cloth for some shirts I want to have made, but don't see anything that grabs me by the wallet. I photograph a beaming woman selling dried fish, who in the usual pattern, after seeing the result on the camera screen, insisted that I take a picture of her friend too. I took great care to make sure the friend agreed to this, because even if she wasn't, I was distinctly uncomfortable with the request. Her friend's t-shirt was pulled up around her neck like a scarf, leaving her topless. An infant concentrated at helping himself from the bar, but this still felt a fairly delicate situation to me. She had no such qualms, so I took a couple of shots to show her. She was thrilled.

It occurs to me that Ghanaians were remarkably modest in general, even men and boys very rarely going shirtless. That said, older women seemed to have no issue—this mother didn't discretely lift one corner of her shirt. Alexis explained that nudity was strictly frowned upon, until child-bearing age and beyond. She had actually had a number of discussions on the subject with the local women. She said they talked about being conflicted between native beliefs and customs, (to say nothing of the practical aspects of living in a clothing-optional climate), and the modesty requirements introduced by Western missionaries, whose religious customs they had adopted.

Our final day, and the road to Accra |

|

A good hour and a half before our schedule departure time, Ntow arrived, then sat around and waited with us, as usual patient and content just to be hanging out. I wanted to say a final goodbye to the friends we'd made in the village so I left him there with Wayne and Alexis while I strolled back into the village. I was more than a little shocked at how indifferent people were. Yesterday they were our buddies, all hugs and smiles, and today as I explained we were leaving had a sort of "you still here?" flavor. It made me think of Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves' autobiographical account of life in the trenches of World War One. The soldiers there had a completely different attitude to life and death, because they had to. Death is always just around the corner, surviving another day is cause for celebration. The living had to keep moving on. Perhaps this was also true here, where life expectancy was so much shorter than ours. They were thrilled and grateful for us to be there, but there were no tears shed over us being gone. Here today, gone tomorrow. Life goes on.

Alexis negotiated by cell phone with a taxi driver she knew. They agree on 50 Ghc for the trip which will take him all day, and at least 150 miles. He knows there are three of us, and each of the half dozen times Alexis calls him during the morning to remind him to come, and to be on time, I've heard Alexis warn him how much luggage we're carrying, but as he pulls up he has a buddy riding shotgun. You had to laugh. One of us said "you know you'll have to leave him here, right?" but this really doesn't sink in until the first of the back packs completely fills the little trunk, so we've still got the other pack, two day packs plus Alexis's overnight stuff to go. Shotgun's one useful purpose is to use his ass to cram the doors shut on us like a station guard on a Tokyo railroad platform in rush hour. Then we leave him standing on the side of the road.

The drive was quite an adventure. The first time we nearly broke down the driver got out to check up on things, achieved nothing, but we were able to carry on. The second time we were able to diagnose the problem as lack of gas. We coughed and spluttered our way into the next filling station which was mercifully close, then had to front him the money for refuelling. He put in a quarter of a tank full—perhaps enough to get him home, but only just. He could barely find Koforidua, one of the largest towns in the country, and by far the largest within 30 miles of Brekumansu but although he argued with us the whole way about directions, he clearly had no idea how to get from there down to Accra, so we relied heavily on our rather-too-large-scale map for navigating.

We stopped for a while in Koforidua. There was a large market there, and we were thrilled to discover that we could not only get the parts we needed to make our shot server souvenirs, we can actually buy them made up. Perfect! The market boasts at least one stall selling some nasty looking traps, and nearby perhaps not by coincidence, a man with half a dozen rats strung from a pole. Speculating and extrapolating wildy on the ancient themes we've experienced throughout the trip, I recall that in Olde Englande rat catchers would advertize both their profession and their skill using just such a display. At least romantically it makes sense that this was also the intent here.

Both Wayne and I needed cloth. Wayne had the rather tall order of getting "several pieces that I'll like" for Cornie. Somehow we succeeded, and she turned them into a stunning wall hanging. My pieces we then took to a tailor who measured me up for some shirts. It will take him three months to make what he promised to have ready in time for Lucy's visit two weeks later, so I will not seen what became of my material until Alexis returns for Christmas 2008, but at least the shirts are safely, finally, in Alexis's hands.

Lunch was excellent, including the next in a very occasional series of cold beers, and a delicious guacamole that Alexis had prepared from the remaining avocadoes Wayne had collected. The driver, who until then had been sleeping in his car/guarding the luggage joined us, as did one of Alexis's Peace Corp buddies, Casey. A street vendor came by and sold the driver a DVD containing 27 movies. Yes, one DVD, 27 movies. Even more incredibly, all the movies on this particular DVD had a religious theme, which is apparently very popular (hence Alexis's hair-raising Passion of the Christ experience on the overnight bus?) I should have bought one just to check out the quality, but I think I've had to pick a different theme.

Lunch was excellent, including the next in a very occasional series of cold beers, and a delicious guacamole that Alexis had prepared from the remaining avocadoes Wayne had collected. The driver, who until then had been sleeping in his car/guarding the luggage joined us, as did one of Alexis's Peace Corp buddies, Casey. A street vendor came by and sold the driver a DVD containing 27 movies. Yes, one DVD, 27 movies. Even more incredibly, all the movies on this particular DVD had a religious theme, which is apparently very popular (hence Alexis's hair-raising Passion of the Christ experience on the overnight bus?) I should have bought one just to check out the quality, but I think I've had to pick a different theme.

In one hamlet we pass a wooden shack, incongruously identified as a photo lab, and a little further along I notice a commissioned letter writer—another sign from a bygone age in more affluent countries, but apparently still able to provide a useful service here. Actually there was a never-ending stream of stores with bizarre or incongruous offerings, "barbering and computer services" "Finger of God Enterprises" (a paint store) "'Allah is Great' Food Joint" "Help from Jesus Wholesale" or the one simply titled "Creamy Inn". I wish I'd made a more diligent list, because we saw dozens that made us laugh out loud, and now of course I can't remember any more of them. Then there were the ones where the wares were obvious enough, but one was still left thinking WTF? Top amongst these were brand new (upholstered) three piece suites. First of all, we'd seen no evidence of a home that had the room to house them, never mind the bucks to pay for them, but what sort of state would they be in after a couple of weeks standing at the side of the road? A close second were open-sided caskets. We pass a car repair ramp and pit right out in the open, which made me realize how infrequently we saw garages and service stations, the vast majority of repairs seem to be made on the site of the incident.

Last stop was the famous wood carving market at Aburi, a tourist trap and no mistake. I had my precious carvings from Boabeng, but was still looking for a largish elephant for home, and more importantly a bunch of little ones to give away. There must have been 20 stalls, all extremely enthusiastic to negotiate the best deals, but I couldn't persuade any of them to sell me little elephants. They all came in sets of half a dozen, each a different size. They claimed (with some justification) that the smallest ones take almost as much time as the biggest to carve, but then their relative manufacturing expense makes them too expensive to sell. So I bought a set, and found an interesting larger one too. Wayne finally bought his mask, an elephant and a hippo too. Shopping complete, we were ready to hit Accra.

Given all the breakdown scares, it was something of a relief when Alexis finally guided the taxi to a halt in the grounds of the hotel. Better still they were expecting us. Well, sort of. As we walked in, the receptionists were sitting out in the foyer, watching TV. This was something of a reality jolt, since we'd not seen such a thing for weeks now, but the far bigger jolt was that there was absolutely no doubt that they were watching porn. The hotel had an interesting arrangement with the Peace Corp, whereby a dormitory-style room was permanently rented to them, so any volunteer can show up day or night, and provided there is a free mattress (or even just floor space) they can get their heads down. Wayne and I have been rented a curious little room right off the lobby, which made it feel more like the bunkroom for the receptionist, and comparing the Peace Corp discounted rate we were paying to those posted in reception, there was possibly some truth to that. Nevertheless it felt very luxurious, with a TV (and DVD player!) and an ensuite bathroom with actual genuine hot and cold running water.

After a quick shower and change, it was time to find a bar. Alexis took us to Duncan's, one of her usual hangouts, a spot that occupied the corner of a busy street intersection. The tables were out on the sidewalk, Paris style. Ahhh. Cold beer again. And before we're half way down them, Alexis's buds start to gather. Some stop and say hello, Ade, George and Raja sit and order a beer. It was too loud to have a conversation across the table, so Wayne ended up talking to Ade, who was hoping to get some business venture going in Liberia but Alexis described him as having "done a bunch of random stuff really." They were all articulate, spoke excellent English, and had travelled or even lived abroad. These were the first Ghanaians wealthy enough to buy us a drink. George was apparently a neurosurgeon, born in Ghana but lived in Cuba for 14 years, through to the end of medical school.

After a quick shower and change, it was time to find a bar. Alexis took us to Duncan's, one of her usual hangouts, a spot that occupied the corner of a busy street intersection. The tables were out on the sidewalk, Paris style. Ahhh. Cold beer again. And before we're half way down them, Alexis's buds start to gather. Some stop and say hello, Ade, George and Raja sit and order a beer. It was too loud to have a conversation across the table, so Wayne ended up talking to Ade, who was hoping to get some business venture going in Liberia but Alexis described him as having "done a bunch of random stuff really." They were all articulate, spoke excellent English, and had travelled or even lived abroad. These were the first Ghanaians wealthy enough to buy us a drink. George was apparently a neurosurgeon, born in Ghana but lived in Cuba for 14 years, through to the end of medical school.

George said "Cuba is a great example to the third world—not the first world perhaps, but definitely for the third world" which at the time I thought was very profound, but none of us can remember what he meant. I think what he meant was that from the third world's perspective, Cuba was the mouse that roared. Cubans may look poor or worse to our Western eyes, but they had stood up to and/or taken advantage of the superpowers, and the people had a reasonable way of life. Who am I to argue? He'd lived there, been through medical school there and now lived in Ghana which he was describing as third-world, not me. The little I know about Cuba is third hand via American media, hardly an unbiased source of information.

Raja was a Web developer. I know nothing about medicine, but I know a little about Web sites, so I asked about that. It was very clear that he knew what he was talking about, and that these were serious web sites (one has to wonder, in a country without power, how much call there was for such a thing, but it seemed clear that at least here in Accra there was sufficient demand.

But as if to vindicate my point, around 8:30 there was a total power failure. We'd had enough to drink, and more importantly, we had an early start in the morning, so we were content to leave, but first I had to pee. It was dark, and pitch dark inside the building, and on top of that I had no idea where to go. One of the guys showed me back into the bowels and pointed down a long corridor lined with beer crates. "Go right to the end, and it's on the right." Well talk about black cats in coal scuttles, I could just make out the even darker opening when I had groped my way to the end. I was expecting the step up, so did not fall flat on my face which probably saved my life. But now came the easy part, since I knew there was nothing in the room but the pipe in the floor leading to the street. So I set about my business. It was long overdue, and I stood there a long time. Long enough in fact, for my eyes to start adjusting to the dark, at which point I was able to make out the distinct outline of the only urinal I ever saw in Ghana. I'd missed it by a mile.

Alexis had other fish to fry, so Wayne and I accepted George's gracious offer of a ride back to the hotel. As we crossed the foyer to reach our room, we noticed a pile of DVD disks scattered on the table with some fascinating labels, including one that fairly obviously was what they'd been watching when we first arrived. I only bring this up because what happens next is such a great example of Ghanaian charm and attention to service. We asked to borrow the aforementioned DVD and take it to our room, but it didn't play in the machine. We're of two minds to just quit, but the whole episode is an amusement, so we go back to the receptionist to complain. He knows what the problem is immediately, and sets about switching out the DVD player. He tests the new configuration and it still does not work. We were only interested for a lark, and we're rapidly getting too tired to care, but he insists that it is no trouble and that he wants to change out the TV set too, which he does. Finally after 15 minutes of pulling and pushing cables and lugging hardware from one room to another, he triumphantly grins as the eye-popping picture comes up. We get ready for bed and have crashed asleep before the opening credits have finished rolling.

We have a 6am start, and we're up in good time to finish our packing. This is the big one—the pack job has to survive the baggage handlers. We pour the precious akpeteshie into our neoprene water bottles, (thereby rendering them useless for any other purpose ever again) I wrap most of my clothes around my large wooden pieces, and we both bury the smaller pieces so deep into pockets and shoes that it took weeks to find it all again. We're ready to check out, but there is no sign of Alexis. Of course there was some wrangling over the price, and we ended up unable to negotiate around a surcharge because we were "two persons of the same sex sharing a room." Perhaps the movie had blown our cover? This rather curious qualification was apparently not a homosexuality tax, but more to do with our sharing being a way to avoid renting a second room from them. There was no denying the logic, we forgot the outrage, and instead began to wonder why this was not a more popular tactic around the world. In anycase, one couldn't help but admire the ingenuity.

Now we were ready to flag down a taxi, but there is still no sign of Alexis. Wayne disappeared into the bowels of the hotel and found the Peace Corp dormitory, and somehow managed to make out Alexis among the mass of bodies crashed on the floor. It is a testament to resilience and low maintenance that she went from the dead sleep start to bouncing out of the hotel bright eyed and bushy-tailed only about two minutes after Wayne reappeared. When she heard our story about the surcharge, she immediately returned to the reception desk, and tried to claim that Wayne was in fact a woman, convincingly enough that the receptionist actually turned to check Wayne out again, and remind himself of how unlikely a scenario that actually was. Nice try. We were impressed.

We flagged a taxi, and armed with the certain knowledge that comes from Alexis telling me in no uncertain terms not to pay more than 3Ghc, easily adopted a take it or leave it attitude that brought the fare down from 10Ghc in a minute flat. The departure hall was the chaos one expects from watching too many movies about the third world. But once again, Ghanaian hospitality worked like magic, and time after time we found ourselves shepherded not just to the right line, but often to the front of it. An hour into the process, I have time to make a note that it is 7:20am, and two hours before boarding, and we're still in the departure hall, and meanwhile they are already calling for boarding. But no wonder, since a big sign above the check-in desks warns travels that they will all shut 90 minutes before the flight—in just 30 minutes. This is the capital of Ghana, and there are just nine flights out of Accra today, an average day. That is probably a good thing, because it doesn't feel like anyone has moved out of the departure hall yet, so if it takes more than an hour to check in one flight, nine is about all you could possibly handle. I kept a log of every check point between the curb and the plane.

The last check before we leave the departure hall finally provides the rubber glove treatment for our luggage, but thankfully not to our bodies. The customs guy pulls out my one liter neoprene bottle filled to the brim with a colorless liquid.

"What's this?"

"Akpeteshie."

"Akpeteshie?! You like akpeteshie?"

"We love it."

"You are taking akpeteshie to America?"

"Yes, is that a problem?"

"No problem at all. We love that you love it."

With that he carefully buried the bottle again, and repacked the bag. We were done. Free to leave the departure hall, we started to make our way to the gate. Meanwhile Alexis was making her way back into town. Unbeknown to us, she had a triumphant day, and finally succeeded in nailing her work permit, thus opening the door to her future career in the US Embassy. The checkpoint log takes up the rest of this story.

Finally sitting in the departure lounge, after going through 11 of the 12 check points and there on the tarmac is the Delta 767 sitting waiting to lift us away. What a beautiful thing. Apart from the couple of planes that scared the crap out of me in the middle of the night as they scrapped the roof off our Accra hotel which was apparently on a direct path to the runway, and the one proverbial silver bird that soared high across the sky one morning in Brekumansu, leaving a thin feathery plume of condensation in its wake, I realized I hadn't seen a single plane in 12 days. At home, if I step into the yard, at any time of day or night, something is there. (I first noticed the consistency on September 11, when suddenly they were gone, and I've been testing this theory ever since.)

Finally sitting in the departure lounge, after going through 11 of the 12 check points and there on the tarmac is the Delta 767 sitting waiting to lift us away. What a beautiful thing. Apart from the couple of planes that scared the crap out of me in the middle of the night as they scrapped the roof off our Accra hotel which was apparently on a direct path to the runway, and the one proverbial silver bird that soared high across the sky one morning in Brekumansu, leaving a thin feathery plume of condensation in its wake, I realized I hadn't seen a single plane in 12 days. At home, if I step into the yard, at any time of day or night, something is there. (I first noticed the consistency on September 11, when suddenly they were gone, and I've been testing this theory ever since.)

Now staring through the departure lounge window, the plane felt like more technology, more power, and a greater cash value than the sum total of everything we'd experienced over the last 16 days. After even so short a period of time, it already seemed like something of a miracle that it was actually sitting there, right on schedule and even more incredibly, it would lift off the ground, and in one 11 hour step deposit us back in the 21st century decadence of western civilization and home. I had the vivid sensation of being 15 again, and the excitement and awe of my first flight.

Ghana has changed me. As I write this section it is four months since we were there, and I think about it daily (no surprise, I'm still writing up the notes) and I feel like Scrooge. I've been given an opportunity to see the ghost of Christmas Past, in the number of times I compared an experience to how things used to be, 50 or 200 years ago. I saw Christmas Present—Ghana is much more a reflection of how the average person on planet earth lives that anything I've been exposed to living in Europe and the US. And the Christmas Future that we returned to of spiraling gas prices, the subprime mortgage crisis, and the quagmire of the current US handling of foreign affairs, all combining to leave me acutely conscious of the privileged, protected, isolated, ignorant lives we lead, the waste of our careless decadence, and how perilously close to the edge of disaster we are flirting. Don't get me wrong: all is not doom and gloom. I'm tremendously encouraged by how quickly America is responding to the market, and I hope that gas prices continue to hold the consumer and the manufacturer's collective feet to the fire. Just today Ford announced it was retooling entire plants, and importing European models as fast as it could go. And this from an industry that responded to Al Gore's Nobel Peace Prize-winning challenge earlier this year by whining that it would take them 15 years to come up with a change in strategy.

It's all very well for those of us who already have everything or too much to say enough is enough, and I'm not sure how I'm going to give anything up, but I've become more of an anticonsumer, more entrenched in my grow and buy local campaign. And I'm haunted by the images and recollections of an entire nation of people who had nothing, but laughed every day. I guess the bottom line is that I do believe we can and should be able to have our cake and eat it too. But if that means things cost more to give their growers and sewers a living wage, then so what? If that means nuclear power and wind turbines in Nantucket then so what? We need to look back on the 20th century as a horror show of lessons and mistakes as a necessary evil, a stage we had no choice to pass through in order to imagine and then develop less harmful technologies. But that means we have to keep moving forward. Meanwhile, if the only reason for bringing power to Brekumansu is the long term strategy that eventually this will turn them into Walmart shoppers, then stop the tro-tro, I want to get off.