Friday, 6 April

We drove flat out to Nashville. Nothing to report. Three hours, 214 miles. Bam. We'd agreed that the first thing to do was visit a distillery, and we'd further agreed that the first distillery would be Nelson's Greenbrier Distillery, which was within Nashville city limits as it happened. It was a good choice. We were just in time for a tour, and our tour guide was excellent. He told a great story, worthy of another rathole reconstructed with liberal help from the interweb.

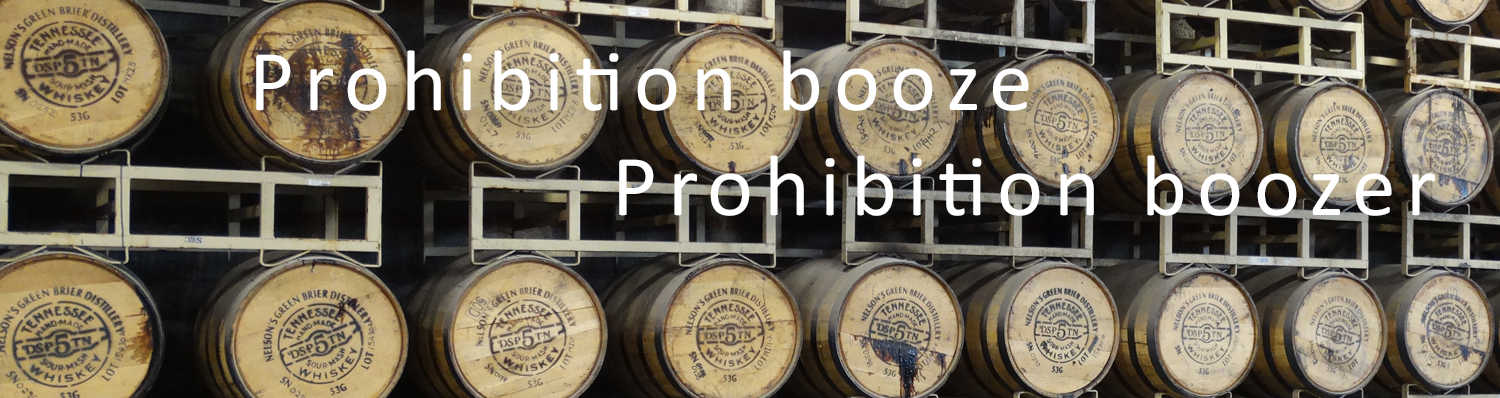

Rathole: Nelson's Greenbrier Distillery Charles Nelson was born July 4, 1835 in Hagenow, Germany. He was the eldest of six children whose father, John Philip Nelson, owned a soap and candle factory. When Charles was 15, his father decided to move his family to America for a better life. He sold his soap and candle factory, converted all of the family’s earthly possessions to gold and had special clothing made to hold all of that gold on his person during the journey. In late October of 1850, the family boarded the Helena Sloman to set sail for America. On November 19, intense storms and gale force winds sent many of the nearly 180 passengers overboard. John Philip Nelson, weighed down by the family fortune, sank directly to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. The rest of the family arrived in New York, but with only the clothes on their backs, and 15 year-old Charles found himself man of the house. Penniless yet determined, Charles and his brother began doing the only thing they knew how to do: making soap and candles. After saving some money, the Nelson family moved west, settling in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was there that Charles, merely 17 years of age, entered the butcher business and acquainted himself with a number of fellow craftsmen who educated him in the art of producing and selling distilled spirits, particularly whiskey. Several years later, Charles set out for Nashville seeking a fresh start. He opened a grocery store which flourished from sales of his three best-selling products: coffee, meat and whiskey. The quality of both his products and service quickly built Charles a reputation that went unmatched in Nashville’s merchant circles. His honesty and fair dealings brought great prosperity for his business as well as an elevated social status in the community. Very quickly however, Charles realized that the demand for his whiskey far exceeded his supply, so he sold the grocery business. Legend has it the blend of coffee was then brought to the Maxwell House Hotel in downtown Nashville, where patrons would later proclaim it as “good to the last drop”. His butcher stayed in business and the store soon grew into a successful Nashville-based grocery chain that is still in business today.  Charles bought the distillery that was making his whiskey in Greenbrier, TN, and a patent for improved distillation. He expanded the production capacity in order to keep up with demand. With this expansion, Nelson was not only creating more jobs, he was making a name for Tennessee Whiskey. By 1885, there were hundreds of whiskey distilleries in Tennessee, but only a handful were producing significant volume. That year, Charles Nelson sold nearly 380,000 gallons, (around 2 million bottles) of Nelson’s Green Brier Tennessee Whiskey. By comparison, contemporary well-known brands had a maximum production capacity of 23,000 gallons. Green Brier Tennessee Whiskey was in such demand that it was being sold in markets ranging from Jacksonville, FL to San Francisco, CA to Paris, France, to Moscow, Russia, and the Philippines. This reach of distribution was possible in part because Charles was one of the first to sell whiskey in bottles rather than selling it by the jug or the barrel. The distillery, which was commonly known as “Old Number Five” due to the fact that it was registered distillery number five and was located in the fifth tax district, became a favorite stop of federal regulators and tax inspectors due to the warmth and hospitality [a lovely euphemism I thought-RT] shown to them by Charles and his employees. It is safe to say that by introducing the category of Tennessee Whiskey to the world and offering a superior product, Charles Nelson had indeed become a household name but after decades of great struggle and brilliant triumph, Charles Nelson passed away on December 13, 1891. His wife Louisa assumed control of the business, becoming one of the only women of her time to run a distillery. In 1909, statewide Prohibition was adopted in Tennessee. This forced Louisa to discontinue operations and Nelson’s Green Brier Distillery closed its doors. The property in Greenbrier was sold and as the years went by the once great distillery was dismantled and fell into disrepair. [Here none of the websites I used to stitch this story together include a detail provided by our own tour guide, and since this narrative is more about a good story than it is about the truth, I'm adding it. RT] Our guide's story goes on to talk more about Louisa, who let's face it must have been quite a force of nature. She ran the distillery steadily for 18 years before its closure—longer than Charles himself did, in fact. But he claims that she then went on to become something of an emancipationist and prohibitionist and in so doing, systematically eradicted the whole distillery legacy from the family consciousness. On a summer day in 2006, Bill Nelson invited his two sons, Andy and Charlie, to help pick up a pig for a family bar-b-q from a butcher in Greenbrier, Tennessee. When the trio arrived they noticed the Nelson name on an old warehouse across the street. The butcher told them about the distillery. "This street is Distillery Road, you know, and that spring, it’s never stopped running. It’s as pure as pure can be.” Perhaps most amazing of all was that the butcher pointed them in the direction of the Greenbrier Historical Society. Here, the Nelsons met with the curator, who revealed her most prized possessions: two original bottles of Nelson’s Green Brier Tennessee Whiskey, and crucially, the meticulous records that one of the foremen had kept of processes, procedures, and recipes: a blueprint for revival. The boys made a pact to bring the family whiskey business back to life. After three years of research, planning and hard work, the Nelsons re-formed the business that had closed exactly 100 years earlier. Nelson’s Green Brier Distillery unveiled their first self-distilled whiskey in July 2017, dubbed First 108 following the footsteps of the brothers' triple great grandfather Charles Nelson and his namesake distillery which was at one point the clear dominant force in Tennessee whiskey, far outreaching a certain local rival who would eventually go onto conquer the globe. |

The tasting at the end was also fun, with our guy explaining why they use Glencairn whisky glasses (a favorite of mine too) and how to exploit their shape when sniffing and samplying whisk(e)y. As expected most of what they had to offer was not exactly to our palette but I actually liked their First 108 (only in small bottles because there's not much of it—they need the rest for maturity) and Nick and Adam liked one of their sweeter Belle Meade bourbons (I thought it had to come from Kentucky to be bourbon?). Perhaps more importantly, our guy was clearly the right person to ask about where we should drink while we were in town. He didn't hesitate: The Patterson House, a speakeasy on the south side of town. Speakeasy? I'm in.

We finished up the tour with the inevitable visit to the shop. I picked up my half-bottle souvenir, and took it to the register. I instantly recognised the man helping at the checkout as Charlie Nelson. He was signing bottles with a fat gold magic marker. Magic indeed. He did the same for Nick and Adam. Score.

Corsair Distillery

Back in the van, I maneuvered out of the parking lot while Adam triangulated the next stop: distillery number two. I had just got the wheels back on the tarmac when he pointed down the street and said: "it's right there." I turned around and put the van right back in the empty spot we'd just created in the lot. We walked down the road, passed an absolutely classic turn of the (twentieth) century red brick factory building. Apparently home of the apparently famous Marathon Car Company their sign was still plain to see on one of the end caps. Famous maybe, but they were in and out of business in four years and that was around the first world war—a hundred years ago now. So a bit of a stretch for a tourist attraction, but then we were not here for the history, we were here for the Corsair Distillery, which we eventually found around the corner on the other end of the building.

Behind the building the road ran straight into a rail road crossing, which was currently blocked by a stationary train. We walked down to take a look. You couldn't see the end in either direction, but we could hear the grumbling of the De-troit Diesels some way off to the front. The train was separating a family from their car which was parked on the other side. Nick and I listened to them debating whether or not to cross through the train. The idea of them trying to duck under gave me the willies, but it seemed perfectly possible to climb up and over. There were steps and gangways. What could possibly go wrong? Even if it started up, you'd still have plenty of time to complete the crossing and climb down the other side. Even if you jumped they were at best only four or five feet off the ground. It seemed simple, but there still felt like a great deal of risk—even I felt it. Perhaps the clear and obvious trespassing was part of the problem. Anyway, eventually one of them jumped on, and of course a few seconds later he was safely on the other side. He behaved like, and was treated like, a hero. Even Nick and I cheered. Spurred on, the remaining three or four pushed and pulled each other on, and scurried to the other side. There was a palpable sense of relief that everyone was safe, and show over we returned to the mission in hand.

Immediately this was not the same experience. The chick behind the bar where we were to buy tickets seemed positively gleeful that the tour that started in twenty minutes was full, but the one an hour from now had a few spaces. We ordered a round of beers while we thought about it. We already had a bit of a buzz on from the previous place which was nice, and we'd already seen how whiskey is made. How keen were we to wait a whole hour to spend money to repeat the experience again? I ordered a three ounce beer thinking I would get a nice little tasting glass souvenir, but instead it was served in what looked like a single-serving plastic ketchup container. With the exception of the Chocolate Mole Stout which was excellently chocolatey and a little kick at the back of the throat from the mole, the beers were not much to write about either.

I wandered around while we were drinking, and to my surprise around the corner I found the tasting room. It was open to the public, you just paid for individual samples. Perfect! We paid for half a dozen between us, and it was plenty. There was nothing that grabbed us except their glassware, which I'm drinking out of as I write. The gin was was particularly disappointing by virtue of its being particulary bad. But this was great: we'd wasted almost nothing in terms of time or money, and there's nothing wrong with something being a bust—it just helps you appreciate how wonderful the good stuff is.

because we got nothin'

because we got nothin' stolen from the interweb

stolen from the interweb All these shots

All these shotsPrince's Hot Chicken Shack

On the way to the hotel, the research department worked on lunch. Hot chicken was the goal, and Hattie B's and Prince's were by far the top rated with Prince's edging the top spot. It's biggest weakness seemed to be that it was further out of town than Hattie's locations, but as luck would have it, that made their original shack by far the closest to the hotel. We tried to do a rolling stop at the hotel but by the time Adam returned to the foyer for a second time to report the room not-ready, once even walking in on a couple fortunately only watching TV, the desk was littered with wrongly coded room card keys, and the clerk was in her own private hell/comedy show of wrongly attributed rooms, and switched room numbers. "Oh thank goodness" she muttered as the manager appeared from the back room. "Oh thank goodness" Adam and I muttered to each other as the manager calmly questioned the clerk and found us a room that was both unoccupied and clean. Armed with apologies and a stiff discount on the room rate we were finally ready to head out on the chicken hunt.

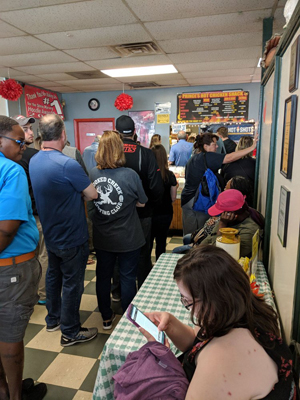

Prince's Hot Chicken Shack was a bit of a misnomer, because being located in a strip mall instead of in an actual shack added something of an air of sophistication. The quality and quantity of the patrons milling around on the outside made our wallets' ass muscles pucker up. We contemplated not stopping, but only for a second. It was mid-afternoon, and this was a highly recommended attraction on Yelp. RT: "What could possibly go wrong?" Chorus: "Err ..." We parked beyond the end of the strip mall, in part to protect the van, but mostly because there was absolutely nowhere else to do so. Having safely navigated through the half dozen or more folks on the outside we pushed on in. No surprise it was packed inside also. So packed in fact that it took a few moments to figure out that almost no one was in line. That should have been a warning flag, but instead we congratulated ourselves on our good fortune and found the end of the line which only had about three or four people in it, setting off the flags and bells with a vengeance. It took at least three or four minutes to serve each person. And when I say serve I only mean to take the order. Then you took your little piece of paper to the cashier who took your money, and then, you guessed it, you were just one of a room full of people paid up and waiting for their order.

The tables were jammed full, but only two or three parties were eating, everyone else was waiting. Two women beside the cashier seemed to be doing a brisker business selling cell phones—or were they giving them away? I never did figure out how that worked. We waited and waited, we took shifts with only two of us in the shack at a time, and eventually a table freed up and we shared it first with a couple of colored girls, and then with two squeeky-clean young men who were the sort of glow-in-the-dark white that you can only get as a Brit, or, as it turns out, by being law students from Montreal. Their girlfriends were back in the hotel because they refused to have any part in this adventure. I gave the guys some credit for coming out anyway (and credit to their gals too for not coming if that's what they preferred).

I think they must have been cooking each chicken individually because when ours finally were called they were piping hot, but so were we after waiting one hour forty-five minutes. A record I hope I never beat. We scuttled back to the hotel, finally, and opened up our packages in the room with the beer refridgerator. We had wisely decided on not-the-hottest level (which Hattie B's described as "Shut The Cluck Up (Burn Notice)" and had settled on what Hattie would have called "Damn Hot!! (Fire Starter)." It was damned hot (I got a serious endorphine rush) and it was also damned good. I'd be very happy to have it again, but we'd have to figure out how to achieve same day service. Sheesh. By the time we were done it was time to suit up for the evening's entertainment: the speakeasy, followed of course by a band.

The Patterson House

I was reading a newspaper article the other day which asked why anyone would want to operate or visit a speakeasy: illegal, expensive, and no quality control (virtually ensuring the lowest possible quality). Indeed the poor quality bootleg liquor was responsible for a shift away from 19th-century "classic" cocktails that celebrated the raw taste of the liquor (such as the gin cocktail, made with Genever (sweet) gin), to new cocktails aimed at masking the taste of rough moonshine. So what about that is appealing enough to want to replicate it? As Louis Armstrong said about jazz, "If you have to ask what jazz is, you'll never know." Many tried to get around the illegal part by selling tickets to some form of entertainment (classically a band) and then offering free beverages to guests, which is why the Hollywood depiction of the speakeasy always seems to have jazz playing. The term speakeasy is thought to have come about because of "the practice of speaking quietly about such a place in public, or when inside it, so as not to alert the police or neighbors."

Fair enough. But to me, the worst parts of that are "illegal" and "poor quality booze". Those are both long gone, and to the contrary, speakeasys typically pride themselves on the high quality of their liquor and their cocktails. For the amusement value they tend to retain the secrecy and lack of signage, some even having passwords that change on a regular basis. So it's fun finding the establishment and gaining admittance, but for me by far the most appealing attraction of all the ones I have tested so far is the rule that prevents entry unless they have a seat/table for you, resulting in a guaranteed civilized, quiet, atmosphere somewhat reminiscent of Sherlock Holmes's London private club.

|

|

|

True to form, there was no indication of the presence of The Patterson House when the Uber driver tipped us out at the junction we'd been assured was the spot. "Go up the steps" was all I remembered from the instructions. There were steps so we went up them. There was a door at the top, and it opened. It was obviously the right door. Inside was a little waiting room, and next to the big door to somewhere else was a waiter stand. A couple of people were already sat waiting. A host appeared and confirmed that there was no space currently, but that if we cared to wait, he didn't think it would be more than 5 or 10 minutes. We definitely cared to wait, and right on cue after about 10 minutes we were summoned and escorted to a table.

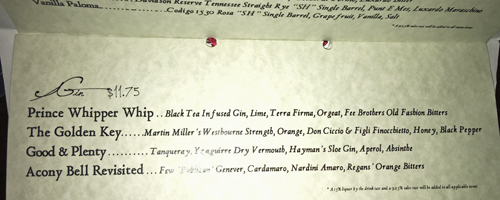

Nothing repeatable or memorable about the conversation, but everything was first class. Those who had turned down the hot chicken ordered some appetizers which were delicious. One drink in particular I liked so much that I asked for the recipe.

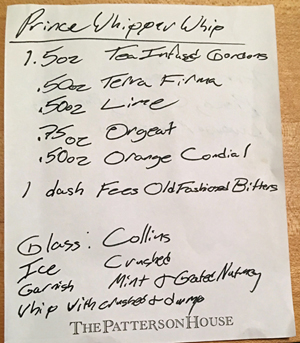

Prince Whipper Whip

-

1.5 oz Tea-infused Gordon's gin

.5 oz Terra Firma

.5 oz Lime

.75 oz Orgeat

.5 oz Orange cordial

Whip with crushes (ice?) and dump into a Collins glass full of crushed ice. Garnish with mint and grated nutmeg.

Terra Firma is a recipe in itself: Pisco; Campari; Pineapple; Luxardo Maraschino

No wonder you drink these things at the cocktail bar and not at home: I have a fairly well-stocked bar and haven't even heard of half this stuff, let alone have it in stock. At least I do know how to make tea-infused gin, which is heavenly just as it is. A project in the making.

If there is one thing I like better than sharing something with someone special, it is sharing something new to someone special. Nick had never heard of a speakeasy but he was an instant fan who tried to persuade us to stay until he'd had everything in the section of the menu he was focussed on. Then he persuaded our mixologist to let him keep his copy of the admittedly rather splended menu as a souvenir.

Jack Pearson

And with that it was time to move on to the entertainment. For tonight, Robin had picked out Jack Pearson whom I'm ashamed to say I'd never heard of, despite his having served several years in the Allman Brothers Band. Greg Allman: "Jack Pearson is tops – he really is. That guy can do it all. As a guitarist, songwriter, and vocalist, he is amazing... There is no question that Jack Pearson is one of the most accomplished cats I’ve ever played with..." After my time I have to assume. But of all the CDs we collected this week, the one of Jack that Nick snagged and had signed for Robin is by far my favorite. We got there as the band was setting up, and I mean that exactly: the band members were bringing their own equipment onto the stage and setting it up. As usual, we had a ring-side seat.

It was only a three piece band but they made a lot of great noise between them. Again my kind of rock and blues a la The Allman Brothers. Nothing much to report except great solos, and a great waitress weaving in and out of the tables, ducking to stay out of the view of any cameras, and always there just as it was time to order another round. At half time Jack came down and chatted to the folks at all the tables to our left, clearly occupied by friends and family. So clear in fact that he then stopped at ours, more or less to ask who we were. We told him we'd come all the way from England to hear him, and that we were having a wonderful time. Obvi.

|

|

|

|

|

During the second set Jack introduced a friend of his, Shaun Murphy, who had been sitting in the audience. Wow. She just took complete control of the band and the audience. A flick of the finger or a glance in their direction and the tempo changed on a dime—or stopped altogether. Another glance and off they went again. No wonder: she sang with Little Feat for 16 years, did a ton of stuff with Bob Seger, and even performed the backing vocals for Eric Clapton's "Behind the Sun" album. That might have been the highlight of the show if Nick (and presumably some others) hadn't spoken to Jack while getting Robin's CD signed at half time, and as a second encore "by popular demand" they played "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed" not by coincidence my favorite Allman's track.

Phew, another incredible day, and just enough energy left to finish the last inch of the Basil Hayden's, and the last couple of beers in preparation for the last day, when some of us at least would need an early (or at least moderately sober) night before the 3am departure on Sunday morning.