Kilimanjaro: Day 4

Wagons Ho!

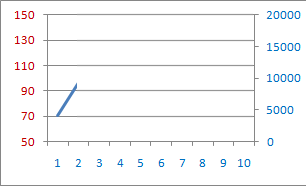

| Night stop: | Forest Camp |

| Elevation: | 9,281 ft |

| Gain: | 5,081 ft 3,381 ft on foot! |

SpO2: |

95% |

| 73bpm | |

| Trek Time: |

3h 15m |

| Distance: |

5.6 miles |

SpO2 is defined and complete tables of these daily numbers can be found on the Statistics page.

Road to the trail head

One of the smoother sections as it turned out.

Photo courtesy and

Copyright © 2010 Doug Day

Hanging from a rafter in the "foyer hut" was a big old-fashioned scale. Everyone had (at least) two bags. One was their day pack, typically containing their toys, their TP, and other more official paperwork, and their water. The other bag was the one to be carried by one's personal porter. There was a strictly enforced 15kg/32lb weight limit for this bag. Everyone had worried about this, because carrying enough to keep warm and dry day and night for ten days, in everything from the rain forest to the arctic, and having the entire bag weigh less than 32lbs was a serious challenge. Some folks had repacked literally dozens of times. Now here was the actual scale, like the hangman's noose hanging from the gibbet. (It doesn't matter what your scale says, if this one says too heavy, then you've got to leave something behind—not an easy decision when everything, by definition, is essential.) Folks who had rented equipment were especially badly off. First the unknown value of the rented part made it impossible to know if you were even close to the limit, and second, now that they could weigh it, their worst fears were confirmed. The sleeping bags in particular were heavier than even the pessimists had allowed. No surprise then that the previous afternoon, and now again this morning, folks were weighing and reweighing. For some strange reason, the first time I'd offered mine up a month or so earlier, I was under the limit—I thought I must have left some things out. As I'd hoped, this scale was more generous than mine, and I was a good two pounds under the bar.

Hanging from a rafter in the "foyer hut" was a big old-fashioned scale. Everyone had (at least) two bags. One was their day pack, typically containing their toys, their TP, and other more official paperwork, and their water. The other bag was the one to be carried by one's personal porter. There was a strictly enforced 15kg/32lb weight limit for this bag. Everyone had worried about this, because carrying enough to keep warm and dry day and night for ten days, in everything from the rain forest to the arctic, and having the entire bag weigh less than 32lbs was a serious challenge. Some folks had repacked literally dozens of times. Now here was the actual scale, like the hangman's noose hanging from the gibbet. (It doesn't matter what your scale says, if this one says too heavy, then you've got to leave something behind—not an easy decision when everything, by definition, is essential.) Folks who had rented equipment were especially badly off. First the unknown value of the rented part made it impossible to know if you were even close to the limit, and second, now that they could weigh it, their worst fears were confirmed. The sleeping bags in particular were heavier than even the pessimists had allowed. No surprise then that the previous afternoon, and now again this morning, folks were weighing and reweighing. For some strange reason, the first time I'd offered mine up a month or so earlier, I was under the limit—I thought I must have left some things out. As I'd hoped, this scale was more generous than mine, and I was a good two pounds under the bar.

Finally only about 15 minutes late, we're all weighed in, the packs are stowed, and we're divided up into four or five Land Rovers. After yesterday's little missing persons adventure, I asked one of the guides if everyone was accounted for, and I figured that's all I needed to know, so I climbed aboard. The wagon train pulled out of Dodge, but we'd only been on the road about ten minutes when the wagon in front of us pulled over to the side of what counts as a road in these parts. We could hear the cursing (in Swahili and English) from 50 feet away. We've left someone behind. Apparently Steve was so engrossed in his packing/repacking ritual, that it was 15 minutes after the ETD before he noticed the time. "Where's Waldo?" became an instant catch phrase, and I think there were people in the crew who actually thought Steve's name was Waldo. Certainly even the guides were comfortable calling him that.

It took a couple of hours to drive to Londorossi Gate, the official entrance, aided and abetted by a number of stops. Principle among these were that we apparently need to check in at some road-side toll-booth that was not Londorossi Gate—so what was it? Finally a colony of Colobus monkeys right beside the road were too good a photo op to miss.

It took a couple of hours to drive to Londorossi Gate, the official entrance, aided and abetted by a number of stops. Principle among these were that we apparently need to check in at some road-side toll-booth that was not Londorossi Gate—so what was it? Finally a colony of Colobus monkeys right beside the road were too good a photo op to miss.

Pulling in under a cattle rancher's gate we definitely then arrived at the actual Londorossi Gate. We are the only clients but there are serious numbers of other folks hanging around, who quickly turn out to be our porters. While we lined up to sign in at the office, the porters all lined up to do whatever it was they needed to do. It certainly looked like they were signing up. I guess it is possible that they were being paid, but given that we needed about 90 of them in all, my guess is that there was not much selecting going on—they were preselected, we were taking all of them. This too made sense. We were a long way from civilization to come on the off-chance of getting a job, especially given how few treks started from here.

Meanwhile, it was my turn to register, and Andrew is watching each of us to make sure we get all the details right: name, address, passport number, date of birth, tour operator, permit number route, blah blah. He must have seen this before on his own sheets, but maybe he'd finally put a face to the name. "Are you really Rick Thomson?" (Rick Thomson is one of the owners of Thomson Safaris.) As a very senior person in the organization, Andrew had met Rick Thomson many times, so he knew perfectly well that I was not the Rick Thomson so I said "Yes, but I didn't even get a discount." So now I was Rick. Hey, it is better than Wayne, who as folks tried to read his name at various times during the trip was called Whine, Way-knee, Way-un, and my personal favorite: Whinnie. Unfortunately none of these stuck.

So is this the official start of the trek? Negatory, plastic chicken. All signed up and ready to go, we piled back into the Land Rovers (not a good sign), which immediately performed a U-turn and headed back out of the gate. WTF? But this answers a question I had from the map: it clearly showed the Londarossi Gate and the start of the trail to be on different trajectories. I had wondered how we were going to get from one to the other. Answer: by backing up the road beyond the edge of the map, to a point where the two paths must join. And sure enough, after about ten minutes we turned off the road onto a track, and into what should have been rain forest.

After a hearty breakfast and a climb briefing, you’ll be transferred to the Londorossi Gate (5,900 ft) to begin your climb. This first trekking day is through dense rainforest (approx. 80 in. precip/yr), under the tangled canopy of moss-coated vines which are home to the black & white colobus monkey, blue monkey, and a vibrant array of exotic birds. Arrive at your camp set in the lower heather belt, and enjoy a hot dinner in the mess tent.

Um, he's helping with traction?

Mick captured the spot where we saw the folks on the inside climbing out of the windows on the left, either escaping or helping with ballast.

Photo courtesy and

Copyright © 2010 Mick Lemmerman

Water

The forests of Kilimanjaro blanket the flanks of the mountain, trapping moisture and acting like a sponge. Today the forest exists in a belt that is in places less than a kilometer thick, and several kilometers thick in others. When Hans Meyer and Peter MacQueen penetrated the region as the first generation of travelers, they found the forest immense, skirting the mountain to the floor of the savannah, graded in density and saturation, and most verdant and concentrated between 4300 to 11,000 ft (1,300m to 3,300m) above sea level.

When the reality of tropical glaciers was finally acknowledged it was assumed that it was from these that the local streams and rivers were fed. It has now been fairly definitively established that this is not so. In fact the forest is key to the survival of the glaciers, and not vice versa. A study conducted in August 2008 reported that deforestation in the foothills of Kilimanjaro has steadily diminished cloud and mist cover on the mountain, which in turn has reduced general humidity, directly affecting the health of the glaciers.

So the steady and general drying of the local environment observed around Kilimanjaro has less to do with a reduction in the size of the glaciers and more to do with deforestation. Kilimanjaro has always been an area of high population density, and in the 130 years or so since colonial intervention a huge increase in the clearing of land for small-scale cash crop production has seen a steady decline in the area of pristine forest on the flanks of Kilimanjaro. Herein lies the root of the crisis.

Already some perennial streams are running dry for a portion of the year, and some seasonal flows have dried up altogether. The forest of Kilimanjaro provides water for communities far downstream of the slopes and hinterland, meaning that millions of people rely on the integrity of just a few hundred square kilometers of threatened forest.

The next few miles were very depressing. We clearly should have been in the rain forest, and the logging trucks passing in the other direction made it painfully clear why we were not. We’d heard about “reforestation” efforts, but those we saw were softwood plantations and crops such as what the driver called "Irish" potatoes—hardly the sort of stuff that would generate rain clouds and trap the resulting precipitation. As we climbed, the destruction thinned and so did the road. Eventually it became the roughest track I’ve ever experienced. Not even the Tazmanian Devil hunt, where there was no track, was as rough as this. At one point, hot on the heels of the Land Rover in front, we watched the occupants all lean out of the uphill windows like ocean yacht racers as the truck lurched sideways and then kicked upright again out of a steep gully.

The next few miles were very depressing. We clearly should have been in the rain forest, and the logging trucks passing in the other direction made it painfully clear why we were not. We’d heard about “reforestation” efforts, but those we saw were softwood plantations and crops such as what the driver called "Irish" potatoes—hardly the sort of stuff that would generate rain clouds and trap the resulting precipitation. As we climbed, the destruction thinned and so did the road. Eventually it became the roughest track I’ve ever experienced. Not even the Tazmanian Devil hunt, where there was no track, was as rough as this. At one point, hot on the heels of the Land Rover in front, we watched the occupants all lean out of the uphill windows like ocean yacht racers as the truck lurched sideways and then kicked upright again out of a steep gully.

Wave your mouse over the picture (or black box) above, and a start button should appear. Press it.

Here's an example Brian managed to catch on video. I don't think it is the same place, but you'll get the idea (from the audio too!)

Finally the road ended in a clearing. The truck being emptied by a small army of porters was not large even by Tanzanian standards, but the fact that it had been driven up the same route we had just experienced was pause for thought. On further investigation we were informed that it sometimes did not make it in one piece. No wonder one web site described this route as “unpopular with tour operators.”

Photo courtesy and Copyright © 2010 Wayne R Munns

Photo courtesy and Copyright © 2010 Wayne R Munns

In one corner of the clearing two long dining tables had been assembled, complete with tablecloths, and laden with food. There was also a basin in a cradle, and what turned out to be one of our mess tent maître d’s stood over it with a kettle of warm water so we could all wash our hands before sitting down. Over the coming days this became quite a ritual—he was very determined not to let anyone into the mess tent (or in this case simply to approach the open-air table) before washing. When I was done, I was tempted to show him the palms and backs of my hands, Dotheboys Hall-style, but refrained.

"Put on your gaiters." What? Gaiters were described as optional, but here was Andrew telling us to suit up before we've taken the first step. Many of us have to scramble to get them back from our other pack, moments before it became just another porter's load. We all wore them all day, every day after that.

Impatiens kilimanjari

The guides rapidly clued in to my need to capture all things Kilimanjaro...

Kniphofia thomsonii

...or Thomson. Grown in western, temperate gardens, better known as Red-Hot Poker.

But finally, finally, finally, we've rested, briefed, weighed in, registered, eaten, gaitered, and donned our day packs. At the mountain end of the clearing a clear path wends its way up into the forest and the guides lead us slowly up it. Wagons Ho!

But finally, finally, finally, we've rested, briefed, weighed in, registered, eaten, gaitered, and donned our day packs. At the mountain end of the clearing a clear path wends its way up into the forest and the guides lead us slowly up it. Wagons Ho!

The Lemosho Route is one of six options for climbing (a seventh path is descent-only). It starts below the Shira Ridge, thus providing trekkers with both a walk in the forest at the start of the trek and more time to acclimatize. Lemosho is the most scenic Kilimanjaro route, from the first day to the last, and it is also the longest (5-8 days each). For some this is a disadvantage—every day on the mountain increases the cost considerably—but for us this is also a huge advantage, giving us the maximum amount of time to acclimatize.

For several days I thought that Antoine hung around with us because he was a friend of our guides. All the other porters went striding past with their loads, but he stayed doggedly with us. He seemed heavier than the others, and was sweating profusely all day, every day. Perhaps they were taking pity on him and helping him along? Oh no. It turned out he was carrying our medical equipment. That sack on his shoulders contained an oxygen cylinder and the Gamow bag. In all his load was around 70lbs. No wonder he was sweating! He was always at the back of the line not because he was tired but because he sure as hell didn't want to have to come back down the path when duty called, plus I imagine that typically the folks in the greatest trouble were also likely to be at the back. When I was the caboose (which I was a lot of the time) that meant we walked together, so he began to remind me of a vulture, circling over the most likely-looking target.

For several days I thought that Antoine hung around with us because he was a friend of our guides. All the other porters went striding past with their loads, but he stayed doggedly with us. He seemed heavier than the others, and was sweating profusely all day, every day. Perhaps they were taking pity on him and helping him along? Oh no. It turned out he was carrying our medical equipment. That sack on his shoulders contained an oxygen cylinder and the Gamow bag. In all his load was around 70lbs. No wonder he was sweating! He was always at the back of the line not because he was tired but because he sure as hell didn't want to have to come back down the path when duty called, plus I imagine that typically the folks in the greatest trouble were also likely to be at the back. When I was the caboose (which I was a lot of the time) that meant we walked together, so he began to remind me of a vulture, circling over the most likely-looking target.

RT Smiling?

Two hours in, and all is well.

Wilson

For my memories.

Copyright © 2010 Richard Thomson