Kilimanjaro: Day 11

The Icing and the Cherry: The Ash Pit

| Night stop: | Mweka Camp |

| Elevation: | 10,065 ft |

| Gain: | 538 ft (9,275) ft |

SpO2: |

88% |

| 94bpm | |

| Trek Time: |

10h ? |

| Distance: |

? miles |

RT and the glacier

It's real. And it is really ...

Photo courtesy and

Copyright © 2010 Wayne R Munns

Wilson on the slippery slope

The slope was steep enough that I was very happy to stand where I was, and I was nervous about Wilson. We still needed him.

Wilson at the camera,

Dr G posin' 'til closin'. Between them, Antoine, of course, is resting.

Wayno and Waldo

Conquering Hero #1

RT "It's all downhill from here."

Adenocarpus manni

Described in the book as "gorse-like" which is comforting, because it looked just like gorse to me.

The following morning I woke at 6am, as usual to the coffee call. Opening the flap to let in the coffee also let in this view. Unlikely to be beaten in this or any other trip, methinks.

The following morning I woke at 6am, as usual to the coffee call. Opening the flap to let in the coffee also let in this view. Unlikely to be beaten in this or any other trip, methinks.

All things considered I felt pretty good. Hakuna matata. It's interesting that the lack of oxygen does not leave you with the panicky feeling that you are suffocating. It’s more insidious than that. There’s just this feeling of lethargy, an overall dulling of the senses. Nevertheless I definitely have the sense of hunger, which is convenient because of course it is breakfast time as soon as you can get out of the tent. There’s no way I can squeeze the bed roll into its quarters without passing out, stuffing the sleeping bag into its sack is a stretch. It is interesting that I can remember very little about the time in the crater. But it can mostly be put back together by the facts.

Andrew was already at the breakfast table for a briefing. We needed to make a choice: straight down, or a visit to the ash pit. To my surprise the first few folks were unequivocal: get me outa here! I reported that if even one person needed to go straight down, and we needed to stick together, then I had no hesitation or regrets in complying. But if there was the possibility of a separate party making the excursion, then I planned to be part of it. In the end six of us signed up for the ash pit.

I did not know that Spence and Stacy were without sleeping bags, otherwise I would have insisted they borrowed all my spare clothing—including my winter jacket which I had no need of, tucked up in my bag. And I did not know that simba were not being offered the ash pit, otherwise I would surely have insisted that at least Bruce was offered the opportunity to join us. I’m sure there were good reasons why the team was not given the option, but surely Mr Shorty-Pants was not it.

The ash pit crew was ready to go, but Waldo’s ass was still poking out of his tent. In a momentary lapse he claimed that he still needed to visit the very-short-drop, but to his credit he quickly remembered his new leaf, and instead scrambled to catch up as we pulled slowly out of the camp.

First stop, five minutes out is Furtwangler Glacier. I had so hoped we’d be close enough to get a good view, and here we were actually leaning against it. Admittedly it was a sort of Disney/Vegas-sized model of itself-about a tenth of the size I’d imagined, but that only reinforced the need to climb the mountain now, before the glaciers disappeared altogether. So this was worth the price of admission already.

First stop, five minutes out is Furtwangler Glacier. I had so hoped we’d be close enough to get a good view, and here we were actually leaning against it. Admittedly it was a sort of Disney/Vegas-sized model of itself-about a tenth of the size I’d imagined, but that only reinforced the need to climb the mountain now, before the glaciers disappeared altogether. So this was worth the price of admission already.

In 1941 Felice Benuzzi and two companions broke out of a prisoner of war camp and scaled nearbyMount Kenya. Even then, 70 years ago, he noted at one point close to the top that "we should have found, according to Dutton's map, Kolbe Glacier; but owing to the general retreat of all glaciers on Kenya, as well as on Kilimanjaro and Ruwenzori, we did not see even the remnant of it." (When they were done Benuzzi and his companions broke back into the prison camp.)

The brilliant white color of the ice allows it to survive as it reflects most of the heat from the intensely strong equatorial sun. The dull black lava rock on which the glacier rests, on the other hand, does absorb the heat; so while the glacier's surface is unaffected by the sun's rays, the heat generated by the sun-baked rocks underneath leads to glacial melting from the bottom.

As a result, the glaciers on Kilimanjaro are inherently unstable: the ice at the bottom of the glacier melts, the glaciers lose their grip on the mountain and overhangs occur where the ice at the base has melted away, leaving just the ice at the top to survive. As the process continues the ice fractures and breaks away, exposing more of the rock to the sun... and so the process continues. The sun's effect on the glaciers is also responsible for the spectacular structures - the ice columns and pillars, towers and cathedrals - that are the most fascinating part of the upper slopes of Kibo. One would have thought that, after 11,700 years of this melting process, (according to recent research, the current glaciers began to form in 9,700 BC) very little ice would remain on Kilimanjaro.

As a result, the glaciers on Kilimanjaro are inherently unstable: the ice at the bottom of the glacier melts, the glaciers lose their grip on the mountain and overhangs occur where the ice at the base has melted away, leaving just the ice at the top to survive. As the process continues the ice fractures and breaks away, exposing more of the rock to the sun... and so the process continues. The sun's effect on the glaciers is also responsible for the spectacular structures - the ice columns and pillars, towers and cathedrals - that are the most fascinating part of the upper slopes of Kibo. One would have thought that, after 11,700 years of this melting process, (according to recent research, the current glaciers began to form in 9,700 BC) very little ice would remain on Kilimanjaro.

The fact that there are still glaciers is due to the prolonged 'cold snaps', or ice ages, that have occurred down the centuries, allowing the glaciers to regroup and reappear on the mountain. According to estimates, there have been at least eight of these ice ages, the last a rather minor one in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a time when winters were so severe that the Thames frequently froze over.

At these times the ice on Kilimanjaro would in places have reached right down to the tree line and both Mawenzi and Kibo would have been covered. At the other extreme, before 9,700 BC there have been periods when Kilimanjaro was completely free of ice, perhaps for up to twenty thousand years.

At these times the ice on Kilimanjaro would in places have reached right down to the tree line and both Mawenzi and Kibo would have been covered. At the other extreme, before 9,700 BC there have been periods when Kilimanjaro was completely free of ice, perhaps for up to twenty thousand years.

But on we went. Andrew had been very smart and not mentioned the route to the pit. Uphill all the way. When we stopped for a breather (there must be a joke in here somewhere) we challenged Wilson about this. "22" Uh-oh, that means trouble. More arm-twisting. "19,300" is his more measured response. GD! That’s only just short of the summit. Okay it’s not nearly as tough as it would have been up that scree slope, but still!

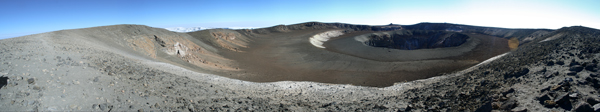

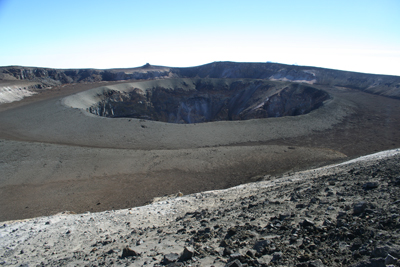

The Ash Pit

We shuffled on up the inclining moonscape. Then we crested the rim. The view was absolutely jaw-dropping. We all just stopped and stared. And stared. You can’t take away the summit, and I wouldn’t want to. But seriously, this was way, way more spectacular. I could not believe how many people came all this way and how few of them had the opportunity to take these last few steps.

We shuffled on up the inclining moonscape. Then we crested the rim. The view was absolutely jaw-dropping. We all just stopped and stared. And stared. You can’t take away the summit, and I wouldn’t want to. But seriously, this was way, way more spectacular. I could not believe how many people came all this way and how few of them had the opportunity to take these last few steps.

For technical accuracy, let's just be clear: we're standing on the edge of the Reusch Crater, and that hole in the middle is the ash pit. The ash pit is almost exactly as deep as it is wide: 130m by 140m. Like I said, this is easily close enough, thank you very much.

Truly a crowning moment in my life, surely you'll indulge me one last mug shot.

Truly a crowning moment in my life, surely you'll indulge me one last mug shot.

.

.

.

.

It's hard to see this in the photographs, but the surface here was, well, ash. Soft and super-fine as powdered snow, you could easily have skied down, but it would have taken a week to slog back up again.

It's hard to see this in the photographs, but the surface here was, well, ash. Soft and super-fine as powdered snow, you could easily have skied down, but it would have taken a week to slog back up again.

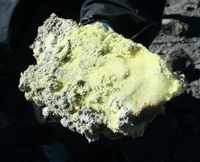

Wilson is standing next to one of the advertized fumeroles, still smoking, and in his hand he's holding the reason it smells of sulphur: it is sulphur. It is too hot to hold, and he did not take long to drop it, despite his gloves.

.

.

Mawenzi - Mawenzi looks less like a crater than a craggy rock emerging from the Saddle (or the clouds). This is merely because its western side is also its highest, and hides everything behind it.

Mawenzi - Mawenzi looks less like a crater than a craggy rock emerging from the Saddle (or the clouds). This is merely because its western side is also its highest, and hides everything behind it.

The peak is actually a horseshoe shape, with the northern side of the crater eroded away. Its sides are too steep to hold glaciers, and the gradients require seriously technical climbing skills.

Mawenzi's highest point is Hans Meyer Peak at 5,149m, but the summit is so shattered that there are a number of other distinctive peaks including Purtscheller Peak (5,120m) and South Peak (4,958m). There are also two deep gorges, the Great Barranco and the Lesser Barranco, scarring its north-eastern face (which again we cannot see).

After cresting Stella Point again, it was downhill all the way home. What took seven hours to climb only took an hour and a half to recover. With his responsibilities complete, Antoine is only too happy to lead the pack for once.

After cresting Stella Point again, it was downhill all the way home. What took seven hours to climb only took an hour and a half to recover. With his responsibilities complete, Antoine is only too happy to lead the pack for once.

Photo courtesy and

Copyright © 2010 Mick Lemmerman

It had been a long day, and we were ready to be done, but as we pulled in to this camp (High Camp, ironically since this is the lowest point we've been at in a week) our tents were nowhere to be seen—we were not low enough yet. So after a water break and a very welcome cleanish long-drop, we had to move on again.

A final example of first class tent-siting by Danken, who mysteriously is not there to great us. The mystery is soon cleared up. Apparently he had a headache and "went home" which is a serious disappointment since being the last night I needed to thank him and give him his tip. I was seriously bummed that he left without saying good-bye.

A final example of first class tent-siting by Danken, who mysteriously is not there to great us. The mystery is soon cleared up. Apparently he had a headache and "went home" which is a serious disappointment since being the last night I needed to thank him and give him his tip. I was seriously bummed that he left without saying good-bye.

Final ascent to Summit. 1-2 hours to Uhuru Peak Arise early and amble your way up the last 600 feet to Uhuru Peak (19,340 ft). Descend the Mweka Route to Barafu Camp for lunch, and then continue to your camp nestled in thick heather.

Antoine plays catchup

dragging his oxygen cylinder behind him. Behind is the camp, and behind that the scree slope we'd skied down the previous afternoon. So glad we did not have to go up that way this morning to summit.

A fist full of sulphur

Wilson holds up a chunk.

Stacy and Spence

The actual subjects of Wilson's pic on the other side of the page (he must be using a telephoto).

Conquering Hero #2

Wayne: "That's another fine mess I've gotten you out of."

Copyright © 2010 Richard Thomson