Tokyo

The Tokyo Story picks up again a week on Thursday, when we returned for one more day prior to our return trips on Saturday.

A tad over-served on Thursday night, we quickly abandoned plans for a dawn walk to the Meiji Shrine and wisely repaired to Starbucks at a more civilized hour for a breakfast coffee and regroup of the day's activities. The new plan was to visit gardens until mid-afternoon, if possible squeezing in takoyaki for lunch, freshen up back at the hotel, then on to the Park Hyatt aiming to be there at dusk for a cocktail in the New York "Lost in Translation" Bar.

Meiji Jingū 明治神宮

This Shinto shrine is dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji and his wife, Empress Shōken. Born in 1852 Emperor Meiji was the 122nd Emperor of Japan, and great-grandfather of the current Emperor. The Empress is famous for promoting national welfare and women's education. The pair played a major role in changing Japan from an isolated, pre-industrial, feudal country dominated by the Tokugawa Shogunate through the political and social revolution to become the capitalist and imperial world power that we know today. (See my brief history of this transformation.)

We were concerned that arriving at the late-for-us hour, and with this being perhaps the second biggest attraction in Tokyo, it would be a mob scene. But this crowd gathered under the first of the torii was what counted as a mob. The path was lined on either side with two huge walls of 72L (19 gal) sake barrels, all donated to the spirits. Another plus for the shinto religion.

We were concerned that arriving at the late-for-us hour, and with this being perhaps the second biggest attraction in Tokyo, it would be a mob scene. But this crowd gathered under the first of the torii was what counted as a mob. The path was lined on either side with two huge walls of 72L (19 gal) sake barrels, all donated to the spirits. Another plus for the shinto religion.

During his lifetime, the emperor was known by his personal name Mutsuhito. But upon his death he was given the reign name, Meiji. His personal name is never used in Japan in any official context. As the reigning emperor is referred to as "Emperor", all deceased emperors are referred to by their given reign name. The correct usage in Japanese is therefore the "Meiji Emperor".

After the emperor's death in 1912, the Japanese Diet passed a resolution to commemorate his role in the Meiji Restoration. An iris garden in an area of Tokyo where Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken had been known to visit was chosen as the building's location.

Construction began in 1915 under Itō Chūta, and the shrine was built in the traditional nagare-zukuri style and is made up primarily of Japanese cypress and copper. It was formally dedicated in 1920, completed in 1921, and its grounds officially finished by 1926. Until 1946, the Meiji Shrine was officially designated one of the Kanpei-taisha, meaning that it stood in the first rank of government supported shrines.

After the emperor's death in 1912, the Japanese Diet passed a resolution to commemorate his role in the Meiji Restoration. An iris garden in an area of Tokyo where Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken had been known to visit was chosen as the building's location.

Construction began in 1915 under Itō Chūta, and the shrine was built in the traditional nagare-zukuri style and is made up primarily of Japanese cypress and copper. It was formally dedicated in 1920, completed in 1921, and its grounds officially finished by 1926. Until 1946, the Meiji Shrine was officially designated one of the Kanpei-taisha, meaning that it stood in the first rank of government supported shrines.

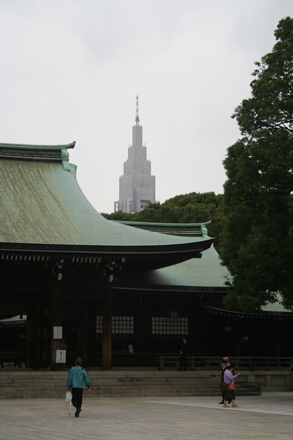

Having passed under the torii, the crowd thinned to nothing again, and we passed several park keepers using traditional twig witch's brooms to hassle leaves off the gravel. The brooms were the perfect instrument, gentle enough to leave the gravel in place, tangled enough to catch every leaf. Eventually we came to the entrance to the shrine itself, and were handed these interesting tickets (left) in exchange for our entry fees. The huge central square was blissfully peaceful. Not deserted, but the couple of dozen tourists just gave it life without in any way being intrusive. It made me wonder if the crowds at Senso-Ji were part of what sucked the spirituality from it. Or more likely the lack of spirituality of the crowd itself was doing the sucking. Had the people been devoted pilgrims, surely that would have added not subtracted. No such distraction here. Despite its size, this one still had the peaceful air of a place with spiritual power.

Novices and monks scurried about. Some were of the female persuasion (but they are not nuns are they?) all were young. We maintained our record of finding some sort of marriage ceremony going on at every major shrine/temple we visited. We wandered about, trying to take pictures, but trying not to take pictures of all the things one was not allowed to take pictures of.

So the monk sitting in prayer, the gaudy statues, pictures, and paraphanalia in the shrine itself, and the wedding preparations I could only stare at, in the vain hopes that I would remember them. At least I remembered that I stared for long enough to write it down here, but that's about all I remember.

So the monk sitting in prayer, the gaudy statues, pictures, and paraphanalia in the shrine itself, and the wedding preparations I could only stare at, in the vain hopes that I would remember them. At least I remembered that I stared for long enough to write it down here, but that's about all I remember.

As usual, the original building was destroyed during the Tokyo air raids of World War II. The present iteration of the shrine was funded through a public fund raising effort and completed in October, 1958. Meiji Shrine is located in an evergreen forest that consists of 120,000 trees of 365 different species, which were donated by people from all parts of Japan when the shrine was established. The forest covers an area of 70 hectares (about 175 acres).

You could buy little charms for luck in pretty much anything you could imagine. I'm not sure if they were directly connected to the Shinto Kami, but it felt like they should be. I bought a pretty pink one dedicated to "loving ties." Hey! It is what it is. Kitsch from Japan. It's the thought that counts. And the profits go back into the shrine. And Claudia liked it despite your sneering.

We couldn't leave without checking out The Inner Garden, even though it was a separate entry fee. Emporer Meiji had designed the iris gardens, paths and fishing spots for Empress Shoken "in order to give her fresh energy" it has "inexhaustable charms ... all the year around." She must have been a special lady, but we exhausted its charms in just a few minutes. The dull light, dug up iris beds, and lack of flowering anything were a bit of surprise. However all was not lost.

We spent several minutes watching a kingfisher hanging out on a branch. Of course we didn't take this picture, even if we'd have had the light he would only have been a speck, if he wasn't a blur too. But I know this was him, because I wrote down a description, and it was just like this. Plus this is the "Common Kingfisher" Dime a dozen resident in temperate climates from Dublin to Tokyo. We had a little more luck with this other little guy (right). Again, this is the only picture I got which wasn't just a feathery streak. Black hood, chestnut shoulders, white cheeks, mottled-looking? "Answers on a postcard please!"

|

|

Kiyomasa-Ido Well was a highlight, said to have been dug by the Edo warlord Kato Kiyomasa, whose family, according to the shrine, had a mansion in the area during the Edo period, although it is unknown if Kiyomasa actually lived there. The site apparently draws masses of visitors who believe it is a power spot where they can experience positive energy. Sadly, it seems the site became famous after some television programs featured it with people claiming that their luck improved when they used pictures of the well as background screens on their cellphones. I guess at times it is so busy you need a numbered ticket to wait your turn. We had to wait for one guy to take an endless series of cell phone shots, but then we had the place to ourselves.

Shinjuku-Gyoen Garden 新宿御苑

Time magazine's "Most Beautiful Garden in Tokyo." Our verdict: Agreed, so far, but Tokyo has not set a very high bar. The shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa bequeathed the land to Lord Naitō (a daimyo, or powerful territorial lord) of Tsuruga who completed a garden here in 1772. After the Meiji Restoration the house and its grounds were converted into a experimental agricultural centre where research was conducted into cultivating the fruits and vegetables now being imported from the west. It then became a botanical garden before becoming an imperial garden in 1879.

The current configuration of the garden was completed in 1906. The 58 hectare garden (145 acres) blends three distinct styles: French Formal, English Landscape and to the south a Japanese traditional one. It was designed by Henri Martinet, a Frenchman (surprise). Most of the garden was destroyed by air raids in 1945, during the later stages of World War II. The garden was rebuilt after the war.

On May 21, 1949 it opened to the public as "National Park Shinjuku Imperial Gardens". It came under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Environment in January 2001 with the official name "Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden".

The current configuration of the garden was completed in 1906. The 58 hectare garden (145 acres) blends three distinct styles: French Formal, English Landscape and to the south a Japanese traditional one. It was designed by Henri Martinet, a Frenchman (surprise). Most of the garden was destroyed by air raids in 1945, during the later stages of World War II. The garden was rebuilt after the war.

On May 21, 1949 it opened to the public as "National Park Shinjuku Imperial Gardens". It came under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Environment in January 2001 with the official name "Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden".

This we have to presume is in the French Formal section. Actually this view is of pretty much the whole section. Quite lovely, and quite unexpected. But it was a bit like going to a "British" Pub in the US: quaint for the locals, maybe, but why disappoint yourself as a tourist?

The English landscape section was not only unexpected, it was almost unnoticed. It was so familiar a view to me, so like any London park, with its rolling fields of grass dotted with trees that served both as a view and as occasional shade, and even replete with families sitting on blankets or horsing around with a ball, that I forgot that it was supposed to be a feature. I guess Monsieur Martinet should be flattered.

The new greenhouse (completed in 2012) was best of show in this "non-season", and its warmth was welcome on this first and only cool day. Obviously it housed tropical and sub-tropical plants (over 1,700 species on permanent display we are assured) but its beauty was in its simplicity and elegance, rather than the somewhat gaudy display of over-sized plants one often gets. I particularly liked this section where the pond went to the window and beyond, a sort of botanical infinity pool.

|

A quite splendid display of staghorn or elkhorn ferns at the greenhouse exit was mounted on a table-height display in the middle of the "foyer" so you could walk all the way around it. The English-only sign said simply "Hands Off." A magnificent work of art that would have been quite at home in the reception area of some grand hotel. Finally on to the Japanese Garden. I'll never tire of them, though the only thing particularly special about this one was being the new best in Tokyo. Several traditional Japanese tea houses were hidden in this section, but as usual it looked like they had been closed for decades even though in fact it had only been a month. |

|

The garden is apparently famous for its cherry blossom display. There are more than 20,000 trees, including approximately 1,500 cherry trees which bloom from late March (Shidare or Weeping Cherry), to early April (Somei or Tokyo Cherry), and on to late April (Kanzan Cherry). We walked past most of them.

Other trees found here include the majestic Himalayan cedars, which soar above the rest of the trees in the park, tulip trees, cypresses, and plane trees, which were first planted in Japan in the Imperial Gardens.

Other trees found here include the majestic Himalayan cedars, which soar above the rest of the trees in the park, tulip trees, cypresses, and plane trees, which were first planted in Japan in the Imperial Gardens.

Literally hundreds of reviews rave about the garden as a picnic spot, hence those hardier souls we had seen in the English Landscape Garden. But I can find absolutely nothing more about the Taiwan Pavilion (Kyu-Goryo-Tei), despite it being an extremely popular photo op. One picture on the interweb makes it look like folks are sitting at tables taking (English-style) tea, but who knows what is actually going on.

The pavilion was at least open on the ground floor and afforded the view above, one at one's feet (above left), the other looking out across the pond (above right). Right is the view from that other side of the pond, looking back at the pavilion. It was built in 1928 to commemorate the wedding of Emperor Showa, and mercifully did not need to be rebuilt in 1945. It is representative of southern Chinese architecture, though it is not clear why, or why such architecture would be revered. And with that, a severe dose of Lunchtime came on.

|

One of my favorite lunches so far had been the takoyaki in Kyoto. Takoyaki in general was also one of Adam's favorites. Strike three, we were currently within walking distance of a hole-in-the-wall Adam had first discovered many trips ago, where he had mistakenly assumed the long-handled spigot on the counter was a beer dispenser, only to find that it actually delivered ice cold, ready-mixed "whiskysoda." It was not an accident then that we found ourselves in the takoyaki bar's vicinity, "because clearly this was tradition that we needed to uphold." It was exactly where he'd left it. "Two takoyakis and two pints of whiskysoda please." |

|

But now what? We still had a couple or three hours before we absoluitely needed to be back at the hotel to change. There was nothing pressing on Adam's list. There was one last garden on my list, but it seemed a long way away, especially with this closing window of time. This is exactly why I hate traveling on my own. Had I been alone, I would never have the will-power to make myself overcome the obstacles, but for a shared pleasure I'm pretty much game for anything. We agreed we had no choice but to take a swing at it. Adam worked some magic on his smart phone, and figured out that although the closest underground stop to the garden required about four changes of train, there was one only about five minutes walk further away that we could reach with only one change. Koishikawa Kōrakuen here we come.

Koishikawa Kōrakuen Garden 小石川後楽園

Oigawa. Not sure if this referred to this striking stone formation, the pond, or the entire scene. Whichever, quite lovely. Capped off with the Tsukenkyo bridge in the background.

Koishikawa Kōrakuen is one of Tokyo's oldest and best Japanese gardens. We totally agreed. Within minutes of entering, it was clear that we had absolutely saved the best until last. It was built in the early Edo Period (1600-1867) at the Tokyo residence of the Mito branch of the ruling Tokugawa family. Like its namesake in Okayama, the garden was named Kōrakuen after a Chinese poem "Yueyang Castle" by Fan Zhongyan: "Be the first to take the world's trouble to heart, be the last to take the world's pleasure" or "a governor should worry before people and enjoy after people." Kōrakuen is translated as vaguely as "enjoying afterwards" and as specifically as "garden of pleasure last" (though one can read that multiple ways too). In another life I think I would love the ambiguity and interpretive possibilities of this language, but for this one I have to settle for bemused and befuddled.

One of the better guide/pamphlet's we'd received, it not only had a map, but also charted two recommended routes through the garden. As always we selected the longer of the two, the "1,400m course, about 1 hours." It seemed to cover pretty much everything so off we went, passed the lotus pond, in which several gardeners were wading about up to their thighs in the muck as they wrestled with the occupants. It looked like the gardeners were losing the battle. It wasn't so much a pond as a rich stew of man and lotus.

Construction was started in 1629 by Tokugawa Yorifusa, the daimyo (feudal lord) of Mito han, and was completed 30 years later by his successor, Tokugawa Mitsukuni. It was once four times its current size, so now it is just an exquisite 20 acres (8 hectares). An exiled Chinese scholar Zhu Shun Shui helped design two of the most iconic features in the garden, the Engetsukyo (full moon ) bridge with its stone arch and reflection creating the perfect circle of the moon, and my personal favorite and trigger for putting the garden on the list in the first place, Tsukenkyo bridge, "a copy of a bridge in Tokyo" (huh? are we not in Tokyo now?) with its striking vermilion paint job contrasting so beautifully with the surrounding greens of the forest.

Construction was started in 1629 by Tokugawa Yorifusa, the daimyo (feudal lord) of Mito han, and was completed 30 years later by his successor, Tokugawa Mitsukuni. It was once four times its current size, so now it is just an exquisite 20 acres (8 hectares). An exiled Chinese scholar Zhu Shun Shui helped design two of the most iconic features in the garden, the Engetsukyo (full moon ) bridge with its stone arch and reflection creating the perfect circle of the moon, and my personal favorite and trigger for putting the garden on the list in the first place, Tsukenkyo bridge, "a copy of a bridge in Tokyo" (huh? are we not in Tokyo now?) with its striking vermilion paint job contrasting so beautifully with the surrounding greens of the forest.

Tsukenkyo bridge was actually next up, first viewed peaking out of the trees behind Oigawa which is either these stones, or the whole pond pictured at the top of this section. We stood here for some time. First off, it was just a great scene. Second, it was something of a relief to find Tsukenkyo bridge so soon, so I could stop worrying about whether we would find it or not. And lastly, perched on one of those rocks in the middle of the pond was a kingfisher, bold as you like. My attempts to capture him on film were beyond disappointing.

The garden represents larger landscapes in miniature, a technique I failed to consciously notice at the time, but which undoubtably contributed to my pleasure subconciously. Rozan, a famous Chinese sightseeing mountain, and Japan's Kiso River are two apparently famous geographic features recreated here along with a garden reproduction of Seiko Lake in China, which is the only one mentioned in the English language pamphlet I picked up at the entrance kiosk, and even that fails to identify which of the ponds it is referring to on the map. We'll have to dig deeper into these mysteries before we return.

The garden represents larger landscapes in miniature, a technique I failed to consciously notice at the time, but which undoubtably contributed to my pleasure subconciously. Rozan, a famous Chinese sightseeing mountain, and Japan's Kiso River are two apparently famous geographic features recreated here along with a garden reproduction of Seiko Lake in China, which is the only one mentioned in the English language pamphlet I picked up at the entrance kiosk, and even that fails to identify which of the ponds it is referring to on the map. We'll have to dig deeper into these mysteries before we return.

Koishikawa Kōrakuen Garden is one of two surviving Edo period clan gardens in modern Tokyo, the other being Kyu Shiba Rikyu Garden, and one of the oldest and best preserved parks in Tokyo. Also best kept secret. Next time.

We weaved around gaining height so that to my delight we actually crossed the Tsukenkyo bridge (that's Adam in the somewhat blurry image further up—it was really quite gloomy in there!) and a few minutes later we were at Engetsukyo (full moon) bridge. The water was still, and so as promised the reflection of the stone arch created the perfect circle of the moon. There were sandbags and other construction material along the stream bank which again presented some photographic challenges.

The rice paddy (a listed feature) again demonstrated the ability to harvest multiple times, with the new crop coming up underneath the drying one. I'm not sure what the red flowers were, but they were the same as the ones in Hamarikyū. and like the Tsukenkyo bridge, their vermillion color contrasted nicely with the greenery all around them.

|

If there was one thing that enhanced the small scale feeling it was the narrow, winding path we were following. It was an ever-changing work of art. Here it was blue stone and cobbles. In other places it was gravel, or stepping stones, or large pebbles. Horai island sat in the middle of a large pond, "a beautiful composition of stone and pine trees" I quote, we agreed. |

|

The garden shows strong Chinese character in its design, as it was influenced by the West Lake of Hangzhou. Once again then, apparently we see the Chinese influence we've also seen in other gardens, and yet today one of the few things we've experienced our Japanese hosts expressing strong opinions on is their distaste for being confused for Chinese, either as people or as product: "made in Japan, not in China!"

The garden shows strong Chinese character in its design, as it was influenced by the West Lake of Hangzhou. Once again then, apparently we see the Chinese influence we've also seen in other gardens, and yet today one of the few things we've experienced our Japanese hosts expressing strong opinions on is their distaste for being confused for Chinese, either as people or as product: "made in Japan, not in China!"

Kōrakuen was appointed as a special place of scenic beauty and a special historic site based on the cultural properties protection law of Japan. All through Japan, there are only seven premises which enjoy double appointments by this Law. They are Kinkakuji, Ginkakuji and Sampo-in of Dogoji in Kyoto, the trace of Nibo-no-miya in the former capital of Heijō-kyō in Nara, Itsukushima Shrine in Hiroshima and Hamarikyū and Kōrakuen in Tokyo. Amazingly, and quite by accident (or was it?) we had visited five out of the seven.

Koishikawa Kōrakuen Garden is adjacent to Tokyo Dome City, which towers over Naitei (Inner garden) the last feature that particularly caught our attention. It looked like a hole on some fantasy golf course. This area was originally kept separate from the main garden, and the Mito Clan maintained a "shoin"-style guesthouse here. A pretty nice spot for a visitor to hang out.

Lost in Translation

It was with fairly heavy hearts though fairly quick steps that we left Koishikawa Kōrakuen to make our way back to the hotel. We still had a pleasant evening to look forward too, but we knew that with our backs to this last garden, our sight-seeing, and therefore the main purpose of our journey was done. Never fear, eating and drinking was right up there too, and we still had plenty of that to do.

Freshly scrubbed and polished we set out for the Park Hyatt. We either screwed up, or it was a ridiculous distance from the nearest underground station, so by the time we finally reeled into the foyer we were ready for another bath, or at least a clean, dry, shirt. We were definitely in a different world, and a distinctly more western one. Everyone in the elevator was speaking English. The hotel oozed that sterile, not-from-anywhere-in-particular decor that always seems to tell me it is not particularly expensive in itself, but to nevertheless expect to be charged for anything and everything as if no expense had been spared. This matched exactly with one of my strongest memories from the movie, which was how depressingly lonely and cold the place seemed. But for all this negativity, there was no question as we walked out onto the 52nd floor, that the New York Bar was a special place. As its website proclaimed: "The stunning New York Bar, Tokyo’s most spectacular venue for live music, features jazz by top international artists nightly. New York Bar offers classic and original cocktails, premium cognac and brandies, and the largest selection of American wines in Japan, in addition to a casual dining menu." It's just that I'm a little too cheap to just relax and enjoy it. Especially when, true to form, we discover the New York Bar's $20 cover charge for non-hotel guests. Each! It was implemented at 8pm, so that gave us a 90 minute window to enjoy a couple of cocktails and the sunset and then skidaddle. We counted that as a win, and a perfect excuse to cut and run before the clock struck eight.

|

But for now, we needed to just relax and enjoy the view. It's what we came for. The surcharge might have bought someone tinkling the ivories of the grand piano parked by the window, instead of it just being an obstacle. Oh well, the view was still pretty neat. So were the cocktails. We had: Radio City: Belvedere Earl Grey, Pink Pepper Syrup, Soda Lost In Translation: Sake, Sakura Liquer, Peachtree, Cranberry Juice Monkey 52: Monkey 47 (Gin), Elderflower Syrup, Cucumber Juice, Lime. |

|

There may have been no cover charge, but the check still fielded the only service charge we paid the whole trip, so an $80 bill for four cocktails. Oh well. It was worth it. Been there, done that. And we will try to replicate the cocktails at home, they were that good.

We decided a fitting way to book-end the trip was to finish in exactly the same way we had started: back to the noodle shop under the railway arch at Shibuya, and then a night cap to say goodbye to Sou-San at Bubbles.

|

|

Bubbles. Since when would I be found in a bar called Bubbles? The outside doesn't look like anything I would ever enter either, but what's the connection with Bubbles? But this magnificent bottle of shōchū? Now that was a story worth following. Everything I feared is confirmed by the card. But I can't get over how everything clashes here. |

|

"Where we come from it is acceptable to buy a good barman a drink." "That works here too." "Excellent. Can we buy you a drink Sou-San?" "I would like that very much. Thank you." With just as much care as he devoted to preparing our drinks, he chipped up the ice, zested a lime, and poured himself a stiff vodka tonic.

East Garden of the Imperial Palace

And there he was: gone. It was a very lonely feeling getting up in the morning, Adam's module yawning empty. Like I said, I'm also not good at being a solo tourist. If I headed straight for the airport I would only be about three hours early, so it wasn't as if I had a whole day to cool my heels. Nevertheless it seemed crazy to waste the three hours. First off, I've already done all the subway trips I need to do, so there is a familiarity. Probably the biggest tourist trap we had not sprung was the Imperial Palace, and not only that, it was walking distance from Tokyo Central Station. The Imperial Palace just wasn't on my radar. Re-reading Eyewitness Travel as I write this, I can see why. Nothing stands out. But somehow I'd come to understand that the East Garden was worth a visit, and it sure was convenient. So the plan seemed obvious. Drag my bags back to the station, cram them into a locker, and see if I could find the palace.

Left: Otemon Bridge, (1) on map. Right: Tatsumi-yagura. A two-storey high keep at the easternmost corner of the Sannomaru and the only keep still remaining in it. AKA another outside corner I passed as I tried to figure out which of the bridges actually allowed one access to the East Garden.

I took my time having a couple of the free bread rolls and a cup of coffee from the dispenser in the foyer. Two people were already sitting at the little counter with their backs to me, which meant I could not but notice that one of them had hair so long it extended below the seat of the stool. As if that wasn't odd enough, when the couple finally stood up, it became clear that the hair belonged to a man who was also wearing those Edo-era/Shogun baggy flared pants that look like a skirt unless you are paying close attention. There was something very formal and dignified about the outfit and the way he carried himself, which completely dissipated any sense of the comic. Admirable. I watched them stride away up the street, and nobody else was staring at him either. I checked out by collecting my shoes from their locker and headed up the street myself.

Left: Fish. (2) on map. I thought it was fab, but guide books and interweb seem indifferent. Right: Cute map picked up at entrance, I added my path, and (1-6) locations and direction of some key photos

The East Garden is entered by crossing the Oteman Bridge Bridge (above) which was the main entrance to the palace until the Nijubashi Bridge was completed in 1888 (more on that later).

Tokyo Imperial Palace (皇居 Kōkyo, literally, "Imperial Residence") —an excellent translation I would say—is the main residence of the Emperor of Japan. Also known as Edo Castle ( 江戸城 Edojō), also known as Chiyoda Castle ( 千代田城 Chiyoda-jō), we are assured that this was a flatland castle built in 1457 by Ōta Dōkan. Today, Imperial Palace is definitely what everyone refers to, but the fortrice-like grounds owe their existance to Edo Castle, and of all these aliases that is by far the most interesting Wikipedia reference. Meanwhile other sources refer to the modern incarnation as "a large park located in the Chiyoda area of Tokyo close to Tokyo Station and contains several buildings including the main palace (宮殿 (Kyūden), the private residences of the imperial family, an archive, museum and administrative offices. It is built on the site of the old Edo castle. The total area including the gardens is 3.41 square kilometres (1.32 sq mi). The circumference is subject to debate, with estimates ranging from 6 to 10 miles. During the height of the 1980s Japanese property bubble, the palace grounds were valued by some as more than the value of all the real estate in the state of California." That seems a bit of a stretch to me—we were in La Jolla once and that seemed a pretty ritzy 'hood, nevermind Malibu, Hollywood, Napa, oh and all of LA and San Francisco? Yes folks in this age of satellite photos, laser survey tools, and digital analysis, the most expensive real estate on the planet has a 40% margin of error on its acreage? There is something quintessential about that. My bafflement, but all my sources' apparent comfort with these facts, seems a perfect example of two cultures with similar standards but totally different attitudes. But valuable stuff anyway, and the vast majority of it off limits. But here we are in the East Garden.

Imperial is a great word. The word that neatly describes the difference between this garden and any and all the others we visited large or small. Elsewhere I have described the shock and awe that Europe's gothic cathedrals must have induced in their congregations, and although this was a castle not a garden when it was built, it was on a scale unimagined before that, and even for a world-weary soldier it must have weakened him in the knees when he saw what he was supposed to scale. But scale it he did.

The East Garden is where most of the administrative buildings for the palace are located, as well as the Imperial Tokagakudo Music Hall, but the feature that totally dominates the whole garden is the remains of the former Honmaru and Ninomaru areas of Edo Castle, a total of 210,000 m2 (2,300,000 sq ft). Several structures that were added since the Meiji period were removed over time to allow construction of the East Garden. In 1932, the kuretake-ryō was built as a dormitory for imperial princesses, however this building was removed prior to the construction of the present gardens. Other buildings such as stables and housing were removed to create the East Garden in its present configuration. Construction work began in 1961 with a new pond in the Ninomaru, as well as the repair and restoration of various keeps and structures from the Edo period. On 30 May 1963, the area was declared by the Japanese government a "Special Historic Relic" under the Cultural Properties Protection Law.

Right: Oshibafu (lawn!), with Tenshudai in the background. In November 1990 H.M. the Emperor held the Daijosai enthronement rite (the first harvest festival of the reign).

The daimyō were required by the shōgun to supply building materials or finances, a method used by the shogunate to keep the powers of the daimyo in check. Large granite stones were moved from afar, the size and number of the stones depend on the wealth of the daimyo. The wealthier ones had to contribute more. Those who did not supply stones were required to contribute labor in tasks, such as digging the large moats and flattening hills. The earth that was taken from the moats were used as landfill for sea-reclamation or to level the ground. Thus the construction of Edo Castle laid the foundation for parts of the city where merchants were able to settle. At least 10,000 men were involved in the first phase of the construction and more than 300,000 in the middle phase. When construction ended, the castle had 38 gates. The ramparts were almost 20 meters and the outer walls were 12 meters high. Moats that were throughout the rough concentric circles were dug for further protection. Some moats reached as far as Ichigaya and Yotsuya areas, and parts of the ramparts survived to this day. This area is surrounded by either the sea or the Kanda river, and therefore allow ships to navigate. Various fires over the centuries damaged or destroyed parts of the castle because of course Edo and the majority of the buildings were constructed out of wood.

On April 21, 1701, in the Great Pine Corridor (Matsu no Ōrōka) of Edo Castle, Asano Takumi-no-kami drew his short sword and attempted to kill Kira Kōzuke-no-suke for insulting him. This triggered the events involving the Forty-seven Ronin.

The main donjon or tower (known as the tenshudai (天守台)) was located in the northern corner of the Honmaru ward. Kitahanebashi-mon is located right next to it and was one of the main gateways to this innermost part. The measurements are 41 meters in width from east to west, 45 meters in length from north to south, and 11 meters in height. A five-storey donjon used to stand on this base which was 51 meters in height and was thus the highest castle tower in the whole of Japan, symbolizing the power of the shogun. The donjon and its multiple roofs were constructed in 1607 and ornamented with gold. It was destroyed in the 1657 Fire of Meireki and not reconstructed. The foundations of the donjon are all that is left.

A fire consumed the old Edo Castle on the night of May 5, 1873. The area around the old donjon, which burned in the 1657 Meireki fire, became the site of the new imperial Palace Castle (Kyūjō 宮城) built in 1888.

The Suwa no Chaya is a teahouse that was located in the Fukiage Garden during the Edo period. It was moved to the Akasaka Detached Palace after the Meiji restoration but was reconstructed in its original location in 1912. It was moved to the present location with the construction of the East Garden. Again, it looked like it had been deserted for years, and how cool it would have been for it to be aglow with light and activity, but I loved it nevertheless, with the wet roof tiles shining in the dull light.

|

As I continued around, I came to another ancient "photo op" in the Ninomaru Garden. In the middle of the picture on the left, you can see the stepping stones in the middle of a sea of pebbles. The main path exits to the left, but the option to the right leads you to this viewpoint sticking out into the pond. As I have elsewhere, I've tried to replicate the panorama that you get standing on the stone. According to the brochure, "the Ninomaru Graden is based on an 18th century garden map. A pond can be found today in nearly the same position as the original garden attributed to Kobori Enshu." It doesn't say where the map came from, or whether it represented anything more than a sketch the designer scratched onto a napkin one night at the bar. Nor why or how the current pond differs from the original. Below left is a better view of the foreground on one's left in the panorama (there always seems to be some carefully arranged detail right at one's feet when standing at these vistas) and behind it the bridge that the path will soon lead me across. The view on the right below is from the far side of the pond, looking back at the bridge again. A pretty enough spot of its own, with every object in it presenting a different texture, color, and line. Kobori Enshu does fine work. Rain drops ripple the surface of the pond and the gentle patter of them against my hood enhanced the tranquility of the scene. |

|

Leaving Ninomaru brought me back to the entrance. The last sight (or is that site?) to see was the Nijūbashi Bridge, perhaps the most famous bridge in Japan. It was across a vast plain of gravel paths and squares of grass, but plenty of folks were hoofing across it in the rain, even toddlers who trotted along as usual, apparently undaunted by their lack of carriers and strollers. I just followed them.

In typical Japanese style, it turns out that despite all the signs at the site, as well as interweb references to the contrary, the bridge is not actually called Nijūbashi. This would mean double bridge, which makes sense. I am assured it is actually called seimon ishibashi 正門石橋, or main entrance stone bridge. This distinguishes it from 正門鉄橋 seimon tetsubashi or main entrance iron bridge, which sits right behind the one in the picture. The font of wisdom I drew this from then goes on to say, however: "When you stand in front of the stone bridge you can see the iron bridge behind it and it looks like there are two bridges" which one assumes they mean to imply is the reason for the name Nijūbashi, double bridge, because no doubt about it, there definitely are two bridges. Personally, I don't know why it's not simply because the stone bridge is two bridges one after the other. I kid you not, this story actually gets way more complicated. Go read it for yourself. Once I found myself reading "the stone bridge was a wooden bridge ..." and understanding what they meant, I knew it was time to stop reading, or stop drinking, or both.

In typical Japanese style, it turns out that despite all the signs at the site, as well as interweb references to the contrary, the bridge is not actually called Nijūbashi. This would mean double bridge, which makes sense. I am assured it is actually called seimon ishibashi 正門石橋, or main entrance stone bridge. This distinguishes it from 正門鉄橋 seimon tetsubashi or main entrance iron bridge, which sits right behind the one in the picture. The font of wisdom I drew this from then goes on to say, however: "When you stand in front of the stone bridge you can see the iron bridge behind it and it looks like there are two bridges" which one assumes they mean to imply is the reason for the name Nijūbashi, double bridge, because no doubt about it, there definitely are two bridges. Personally, I don't know why it's not simply because the stone bridge is two bridges one after the other. I kid you not, this story actually gets way more complicated. Go read it for yourself. Once I found myself reading "the stone bridge was a wooden bridge ..." and understanding what they meant, I knew it was time to stop reading, or stop drinking, or both.

I had to wait a while for this shot—when I first arrived at the scene it was half a dozen deep in spectators, and I could barely see the bridge. This is another one of those shots that I like so much more in hindsight than the "document-the-moment" emotion that I snapped it in. Now I love the umbrelllas, and the strands of new growth on the trees blown sideways by the breeze.

Ironically, the only thing I remember taking particular care over in the composition is to completely occlude seimon tetsubashi, the iron bridge. I was here to see seimon ishibashi aka Nijūbashi which for reasons I now cannot apparently defend, I came to believe was the "official" end of the Nakasendo. It makes sense: folks travelling the road were doing so to pay their taxes, and who else would they pay them to but the Emperer, but now I can't find the references to confirm that.

Ironically, the only thing I remember taking particular care over in the composition is to completely occlude seimon tetsubashi, the iron bridge. I was here to see seimon ishibashi aka Nijūbashi which for reasons I now cannot apparently defend, I came to believe was the "official" end of the Nakasendo. It makes sense: folks travelling the road were doing so to pay their taxes, and who else would they pay them to but the Emperer, but now I can't find the references to confirm that.

So I stood around in the rain, enjoying the so far from home, so isolated, so alone, and yet so content, so safe, so "I'll be home tomorrow" feeling that I often have when I'm warm and dry but the rain is pattering audibly against my window/umbrella/poncho, and I waited patiently for my final shots. There were sentries standing in these little guard huts, but lacking the ability to capture their faces, I prefer to remember them this way, at the end of the bridge, across the moat, defending the entrance to the Imperial Palace itself.

And then I was done. Back to Tokyo Central Station, retrieve my bag from the left luggage locker (plenty of choices this time), back on the NEX express to Narita, and hence to Los Angeles, and finally Boston, and home. What a trip.