Winter Park is a suburban city north east of Orlando. The resort community developed rapidly after 1880 when a South Florida Railroad track connecting Orlando and Sanford was laid a few miles west of Osceola. The pretty group of lakes just east of the rail bed was developed by northern business magnates including Loring Chase who came to Orange County from Chicago to recuperate from a lung disease. They enlisted the help of a wealthy New Englander, Oliver E. Chapman, and together over the next few years they plotted out the town of Winter Park, opened streets, built a town hall and a store, a beach and boat launch, planted orange trees, and required all buildings to meet stylistic and architectural standards. Our friends Pete and Jill brought us here to take a boat trip around the lakes, to stroll through the town to admire the architecture and find lunch, and then to visit the famous Morse Museum, and its fabulous collection of Tiffany glass.

First stop then was the lakes boat trip. We parked the car in the center of town and walked the couple of blocks to the boat launch. The completely rectangular tub that was the boat held about 20 passengers, with the pilot and guide hunched behind a little steering wheel at the front. I'm always amazed at how knowledgable, enthusiastic, and most of all patient all these docent/guides turn out to be, and this one was no exception. We made straight for one of the main attractions (for me anyway) a canal connecting to a much larger body of water. What I think were southern live oaks draped in Spanish moss hung low over the canal putting it permanently in the shade. Fun fact: French explorers dubbed it ‘Spanish Beard’ as an insult, so the Spanish then named the moss ‘French Hair.’

We puttered around the large lake while the guide regaled us with the history of the area, and then back through the canal he had stories about many of the houses which were more prevalent and closer to the water as we did a slow lap around this smaller body.

We found a nice cafe for lunch, and sat outside where it was less crowded but only just warm enough (hence the availability). Next door was our favorite kind of arts and crafts shop, and the four of us putzed around for a good half an hour. There were several things in there that I would happily have brought home had there been room and budget, especially a 6 ft long metal shark made of junk yard odds and ends. We had neither and left empty-handed.

On to the headline: the Morse Museum and the world’s most comprehensive collection of works by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), including the artist and designer’s jewelry, pottery, paintings, art glass, leaded-glass lamps and windows; his chapel interior from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago; and art and architectural objects from his Long Island country estate, Laurelton Hall, displayed in a specially commissioned wing opened in 2011. It is the largest repository of these materials anywhere.

Laurelton Hall, built between 1902 and 1905 and destroyed by fire in 1957, is arguably Tiffany’s greatest work of art. The artist directed every facet of the estate’s construction, from the room interiors and architectural details to an extensive scheme of gardens and fountains. The exhibition features the restored Daffodil Terrace and approximately 200 objects from or related to the estate. These include prize-winning leaded-glass windows, iconic Tiffany lamps, custom--furnishings, as well as art glass and pottery in Tiffany’s personal collection. In addition to the terrace, the 10 galleries at the Morse showcase surviving components of Laurelton Hall’s dining room, living room, and reception hall—also known as the Fountain Court—as well as other rooms, creating a uniquely immersive experience.

The Daffodil Terrace is installed in its own glass-enclosed gallery, with a view of an expanded garden courtyard in a manner related to its original location at Laurelton Hall. The 18-by-32-foot outdoor terrace exemplifies Tiffany’s unique and dramatic style. Supported by eight 11-foot marble columns that are topped with bouquets of glass daffodils, the terrace’s coffered ceiling is composed of hundreds of stenciled wood elements and molded tiles in three bays. The central bay features a skylight covered by six large panels of iridescent-glass tiles in a pear-tree motif. Pieced together from more than 600 distinct parts and fragments, the terrace is the Museum’s most significant conservation project since reassembling Tiffany’s chapel interior from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Highlights from the dining-room installation include: a 13.5-foot-high, mosaic-decorated marble mantelpiece that is one of Tiffany’s most forward-looking designs; a 25-foot-long Oriental rug; a domed leaded-glass chandelier 6.5 feet in diameter; and a suite of six leaded-glass Wisteria transoms. The living room installation showcases four leaded-glass panels depicting the four seasons—each from a single window displayed in the Tiffany exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, for which the artist won a gold medal. Five turtleback-glass hanging lamps suspended from an iron oxbow fixture made to the specifications of Tiffany’s original serve as the focal point for the gallery. The exhibit of objects from the Fountain Court includes the four-foot-high fountain vase that was its centerpiece as well as a millefiori blown-glass hanging shade.

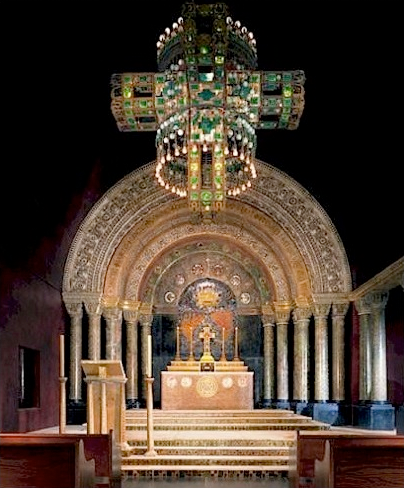

Around the corner from the Laurelton Hall wing is the equally famous and spectacular Tiffany Chapel interior, exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The chapel interior was installed in the Tiffany & Co. pavilion in the Exposition's Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. The chapel’s rich, Byzantine-inspired interior is built up from simple classical forms, columns, and arches, which are huge in size relative to the chapel’s intimate space (1,082 square feet, including the baptistery). Visitors enter another world of intricate, reflective glass mosaic surfaces and light filtered through the intense colors of stained-glass windows—a world that envelops them and at the same time dwarfs them through its massive architectural forms. The chapel includes six ornately carved plaster arches, 16 mosaic columns, a 1,000-pound, 10-by-8-foot electrified chandelier, or “electrolier," in the shape of a cross, a marble and white glass mosaic altar, a baptismal font, and several windows. |

The 8-foot chandelier in front of the carved arches. |

One of several windows. |

The building was freezing. We were all cold, but eventually Pete couldn't take it any more, and he had to leave. Claudia and I were a little better off, because we were used to carrying a jacket with us when we travel in the US. The warmer it is outside, the colder they keep the inside. So whatever the weather, one seems to need to put something on, or take it off each time one transitions in or out. But even we were still uncomfortable.

Jill and we carried on for a while, but our hearts were not in it with Pete sitting outside. Ever the gentleman, when we finally joined him he'd been to fetch his car, so our ride was right outside. We made one last pass down the main drag looking for where we'd parked the hire car, then said our good byes. Another excellent day out.

What better contrast to this day of art and culture than to end it with dinner in Disneyland? I kid you not. Claudia's sister Caroline was at a convention at the Swan and Dolphin, and so despite our promises to ourselves, we found ourselves on World Drive. We actually had a perfectly good meal without too many kids screaming and of course it was fun seeing Caroline, especially so far from our usual habitats and it somehow seemed a lovely way to cap off our hectic adventure.