Lake Pamamaroo-White Cliffs

|

As usual, Wayne got up before dawn and set off to explore the water lead we got last night at the bar. I got up at a more reasonable time, then around 7:30am set out on foot to explore the Darling. It is a bright clear morning, and already a lot warmer than yesterday. In Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories, the elephant child sets out for "the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River." For some reason this image captivated me as a child, and I've never forgotten the alliteration. Kipling was also describing the Darling. However on this waterless continent where most rivers are dry beds most of the year, this "great" river was probably only about 100 feet across. I spent about half an hour wandering along the bank taking pictures of the grey-green greasy water and the pelican floating on it.

|

| Then I returned to the motel. By the time I'm done packing and checking us out, Wayne has returned. He's very excited about Lake Pamamaroo which has indeed provided some compensation for yesterday. The maids are sitting sunbathing outside our room waiting for us to vacate, and in our hurry to evacuate we make a tragic error—neither of us checks the refrigerator, which contains the last of our rum. |

|

| While I checked us out I enquired about the roads. The son/historian made a call and a recorded message confirmed that the roads are all still closed. But the message is from 6:30am, and we were expecting an update around 9:00am. Wayne and I agree on a game plan: we'll go back out to the lake, and when we're done, we'll call one last time. It's a twenty minute drive, and once we're off the main road it is dirt track. There are a couple of soft spots but in general it seems fine. |

|

| Most of the birds have disappeared (no surprise, that's why you need to be there at day break) but we spend a couple of hours photographing the spoonbills, cormorants, and pelicans. It is much warmer now and the flies are so thick I worry about trapping them inside the camera as I change lenses. |

|

In the roadside mud are bouncing track marks, like dinosaur prints. I pace out the distance between the prints. The three or four pairs of marks are remarkably consistent, spaced around 9 or 10 feet apart. |

|

| |

|

| On the way back to the main road we stop at a caravan site to see if we can find a phone and avoid going all the way back into town if indeed we are going to need to continue retracing our steps. There's no public phone, but the woman in the store volunteers to call for us. The roads opened at 11:00am. We celebrate by buying ice-creams from her, then head back to town. Sure enough, as we head out the other side, the sign at the beginning of the dirt has been flipped over to open. It is 152km—just under 100 miles—to Wilcannia where we planned to rejoin the Barrier Highway and all 152km are dirt. About 5 miles in, a sign for folks about to enter Menindee says "Carrying Fruit? Eat it Now!" Some literature we are carrying advised us that all fruit and vegetables should be deposited in the bins outside Broken Hill, but we never saw the bins. But clearly these folks take their pests seriously. |

|

|

It soon becomes obvious why the dirt road rules are so strict. The road is incredibly flat. It is perfectly easy to travel at 70 miles per hour on it. Unless someone has ignored the regulation, and left a rut, which can be pretty exciting when tackled at these speeds. As usual we stop and photograph everything that is still identifiable. The road has its share of road kill, including an emu, which is a fairly major obstacle even now that it is no longer a moving target. Finally the obstruction is something still on its feet. |

It is big enough to be a kangaroo, but the shape and gait are more like a lizard. But it is way too big to be a reptile. As the car finally comes to a halt about 15 feet from it, we have to believe our eyes. It is a lizard, but it is at least 5 feet long.

|

|

Later research indicates that it is a Lace Monitor. It may only have short legs, but it could run like the clappers. It shot under the wire fence and (apparently conforming to habit) scrabbled up the nearest tree. Fortunately for us, the tree was only two or three times as tall as the monitor, so after we'd carefully maneuvered our wedding tackle over the barbed-wire, the monitor was still within view. It's head was chest height, but there was still a good portion of tail on the ground. We snapped pictures until it got bored with us and moved into a less photogenic spot along a branch.

|

|

|

|

Lace Monitor

The Tree Goana or Lace Monitor, Varanus varius, is Victoria's largest lizard reaching a snout vent length of up to 760 mm, and a total length in excess of 2 m. It is very dark, usually with lighter yellowish banding. As one of its common names suggests, this is a semi-arboreal species. It is an opportunistic carnivore, feeding mainly on mammals, birds, reptiles and carrion.

Females lay 4-14 eggs in a clutch,

often in an active termite mound, where the constant temperature and humidity are ideal for incubation.

It is quite common from far East Gippsland through to the Healesville area, and along the Murray river system and lakes of north western Victoria. It lives in holes in trees.

White Cliffs

Born from the discovery of seam opal in the 1890s, White Cliffs is Australia's oldest commercial opal field. The real way to see White Cliffs, if the photographs are to be believed, is from the air. It looks like a strange moonscape, with over 50,000 craters, the result of 100 years of mining. White Cliffs is about a 3hr drive on surfaced road from Broken Hill. The 100 km road from Wilcannia (974km NW of Sydney) runs through scrubby, semi-desert saltbush plains inhabited by kangaroos and every imported feral pest (cats, rabbits and foxes) known to the Australian bush. White Cliffs is located 122m above sea level and has a miserably low average annual rainfall of 234mm.

Arriving in White Cliffs is like arriving in any opal mining settlement. It is immediately obvious that every regular activity comes a bad last to the one thing which drives the town—seeking a fortune! The pub is dusty and lonely, the general store is small and simple, the roads are rough and unsealed, the settlement is spread in every direction, and the attempts at civilization are crude and simplistic. White Cliffs housing operates on the iceberg principle with most of the town's buildings being underground. For every building you see on the surface there are as many as ten more underground.

It is known that opals were found in the area as early as 1884 but it wasn't until 1889 that any real interest was shown. 1889 was a year of drought and four kangaroo shooters were hired to reduce their numbers on the Momba Pastoral Company Station. The roo shooters found opals and realizing their potential value sent them off to Adelaide for valuation by a man with the improbable name of Tullie Cornthwaite Wollaston. Wollaston was sufficiently impressed with the samples to make the journey from Adelaide to White Cliffs. He subsequently became the town's promoter, selling White Cliffs opals in Europe and the USA.

The town peaked in 1902 when opals worth about GBP140,000 were found. The area continued to attract large numbers of miners until about 1914 when the combination of declining opal deposits and the call of war saw the town reduced to the small settlement it is today. The town's decline continued, however the patronage of the nearby rural workers and property owners ensured that the pub and the General Store survived. Today the permanent population is around 200 and this rises to about 500 in winter when gem seekers come from the south. In 1987 the production of opals from the White Cliffs fields was estimated to be $150 million.

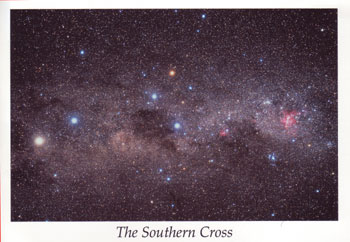

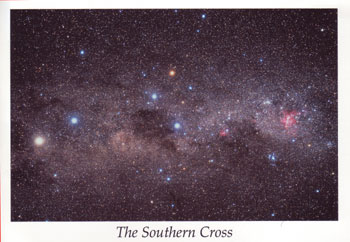

Southern Cross

Because it is not visible from most latitudes in the Northern hemisphere, Crux is a modern constellation and has no Greek or Roman myths associated with it. Crux was used by explorers of the southern hemisphere to point south since, unlike the north celestial pole, the south celestial pole is not marked by any bright star.

The cross has four main stars marking the tips (alpha, beta, gamma and delta).

These four stars are on the New Zealand flag. A smaller star (epsilon), separate from the cross, is included on the Australian flag. Two bright stars, alpha and beta Centauri, are pointers to the head of the cross.

Alpha Centauri is a triple star. It has: a close double star plus a distant, faint, red star called proxima Centauri. Proxima Centauri is the closest star to our solar system.

Do not be confused by three crosses in the Southern sky. Only the smallest and brightest cross, with two pointers aimed at the head of the cross, is the true cross. The brightest star (alpha Crucis) is at the foot of the true cross. The pointers lie to the east. The false cross even also has two pointers, but they point to the bottom of the cross not the top.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

After that of course, everything seemed ordinary. We pass a bunch of Black Cattle, three houses, and two other cars. Although we can fairly consistently see gums lining the bank of the Darling, we never see the river again until we emerge on the main road and cross north of it at Wilcannia. |

|

|

Like Menindee this was a bustling port once upon a time. Miners heading for White Cliffs alighted here and then pushed a wheelbarrow across the last 60 miles of desert. We contemplate this sobering thought as we cover the distance in less than an hour of air-conditioned comfort.

Left: there are kangaroos in this picture, in classic Quantas pose. |

|

This is truly outback sort of country. Even in the green of spring, the red, bare rock and soil is the predominant color. I have no idea what a mining town looks like, but when I conjure up the picture of a place still active but with a population about 10% of when it was at the turn of the 20th century, this is exactly what I imagine. Nothing is rotting or rusting, because there isn't enough water.

|

So around town, and out in the minefield are bits of old-but-clearly-still-used machinery, and lots more bits of old-but-clearly-not-used-for-a-very-long-time machinery.

There's a similar tired but well-used look to the buildings, one of which has "pub" spelled out in old and fading paint above the door. But the door looks like a regular hollow interior door with no windows, no signs, no other sign of life. For grins, Wayne twists the handle. The door opens, and there is a bar inside, complete with barman and three or four other patrons. Nobody looks like they've had a haircut in twenty years. Hell, some of them don't look like they've even washed it since then. Still, as usual, they are welcoming, and they have cold beer, which we buy. |

|

|

| Two more miners come in. One is a clearly a woman, but other than that she looks just like the other guys. One of the men remarks that she's dressed up for the evening. "Well, I put a clean shirt on." The shirt is as dusty as everyone else's, and as threadbare. In short, no one looks like they can afford a pot to piss in. How can they afford to be sitting around buying beer in a bar? I tell you all these details because what happens next comes as a bit of a shock. First, a cell phone starts to ring, and the woman pulls it out of a pocket and answers it. |

|

Who knew you'd get a signal out here, never mind that someone would be able to afford to use it? Then, when she's done, she pulls out a credit card and asks the barman to use it to give her A$100. Which he's promptly able to do. My mind reels with the incongruity of the place and the people, and the technology and the wealth. There's something profoundly heart-warming about it. These folks are clearly content and adequately financed on what to us seems like subsistence living. |

|

Then on to the motel. As we pull in, we're disappointed to see a pretty conventional-looking motel, with parking places under an awning, and a couple of rooms that appear to be bedrooms but which are clearly above ground. We start imagining rooms painted to look like caves. But it soon becomes clear that although the front of the motel, where the kitchen and bathrooms are, is above ground (necessary so their water requirements can be disposed of without pumping them uphill out of the ground, the thirty or so bedrooms and communal areas such as meeting rooms and a bar, are all genuinely below ground. |

|

|

Which brings me to one of the more incongruous aspects of renting a cave for the night: the walls are rough hewn—you can still see the jack-hammer marks—but the floor is carpeted. There is method to this madness however. Outside, the temperature can vary between 0 and 50 degrees centigrade. In the motel, the temperature is a constant 22 degrees, with no heating or air conditioning. Which is also good, because power is in short supply. |

|

They actually have one of the world's first solar voltaic power stations here (converting sunlight into electricity) but this is not enough to support the town. Water is in even shorter supply. Now there are not even any carafes of water in the room, because it was too wasteful throwing out what guests didn't drink.

In addition to the constant temperature, there is also constant light (none) and perhaps all too literally, it is quiet as the grave. |

|

We check in, then decline dinner because we want to be out at sunset. We tour the mines, then head back out of town a little way to where we'd seen some interesting colors in the plants and dirt, and sure enough the sunset light was spectacular. |

|

|

As it got too dark we returned to the motel, another beer with the owners, and when the discussion turns to our need to see the Southern Cross, she invites us to join the dinner guests who will shortly go up on the roof for a little star-gazing. We finally saw the Southern Cross, though it was extremely close to the horizon, making it difficult to discern. It was clear enough to see the Milky Way (which some folks claimed to be cloud cover it was so distinct) and also the Magellan Clouds which comprise two galaxies far far away. |

|