Three Sisters-Bridge Climb

The hotel has a great deal on for all-you-can-eat breakfast. A$5 for "continental" and A$8 for full, cooked works. We decide to do the Three Sisters first, then come back to the hotel for breakfast and packing. So it is not much after dawn when we show up at Echo Point, which is only a mile or so from the hotel.

|

It is a beautiful morning, and Echo Point turns out to be a cliff edge. The visitors area is an acre of paving, right out to, and in some places cantilevered out over, the edge. A knee wall topped by a fat gleaming snake of hand-rail is all that prevents us from being blown over the rim. We are standing on top of the world, or perhaps, rather at the edge of the world. A sea of cloud churns below us, crashing in slow-motion against the cliffs of the islands that stick up out of it in tiers all the way to the horizon. |

|

The sun is coming up behind the Three Sisters, so although we have a great view from where we are (no surprise) the lighting is not good, so we decide to take the path that appears to lead round to the other side of the rock formation. There's also a thing called the Giant's Staircase in the same direction, so we set off to investigate. The path around the cliff is wide, well-maintained, and for the most part well back from the edge. The vegetation is also thick and distracting—ancient ferns the size of small trees. |

|

After about five minutes the path emerged directly behind the Three Sisters. We are right about the sun—we're out in it now, and as a result the temperature has risen dramatically. Since they project out into the canyon perpendicular to the cliff face, this meant we could only see the first sister, the other two were obscured behind her. Looking down, about 50 ft directly below us we can see a bridge out to the sister. According to Bill the valley floor is 6-900 feet below, but we can't see it because it is enveloped in cloud.

The Giant's Staircase isn't a staircase at all. It reminds me more of a ship's ladder: almost vertical. Unlike the ship's ladder, it does not feel firmly anchored, and it does not have a railing on both sides. Sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn't. Also unlike the ships ladder, the steps are uneven, sometimes metal, sometimes carved (and worn) out of the sandstone. I'm totally ill-equipped for the descent: I have two warm layers on, and I can't take them off firstly because I can't carry them, and second because the outer one has a pocket that is (almost) big enough to hold my telephoto lens. |

|

But I'm not comfortable letting go even on even ground, so although the pocket supports the weight, I still feel the need to keep a hand on the lens to keep it from falling out. Here I feel the need to keep a firm grip on it. The only thing that is firmer is the vice grip my other hand has of the railing.

By the time I get down the 50 feet to the bridge, I can feel the sweat trickling down my spine, and all I can smell is the the iron from the rust that I've dissolved from the railings and which has turned my palms a rather lurid shade of orange. There's a sign on the sister asking folks not to climb on her. It is 50 vertical feet up from here, and apparent another 700 feet down. But apparently folks used to take picnics on to the top. I suggest to Wayne that at this is perfectly splendid place for me to stop and admire the view, and that he's welcome to keep going. I have no great desire to see the valley floor, nor to take any further steps that might expedite my progress towards it. |

I sit for a long time watching the clouds slowly swirling through the valley below, and then realize that even if I can't go down, I still have to go back up. I wait some more, and finally decide that leaving without waiting for Wayne allows me to take as long as I need for the ascent. And he can probably figure out where I've gone. The ascent, taken very slowly, without looking up or down, and stopping whenever I felt like it, made the return fairly hassle free. But all the time I'm thinking if I'm like this on the ground, what madness is it to think I can walk over the top of the Sydney Harbor Bridge? What a luxury it is to stand on terra firma in the Men's room and thoroughly wash off the orange stains from my relieved palms. Then I sit in the sunshine and wait for Wayne who finally returns looking almost as pale as I felt. The climb back was about as much as he could deal with physically, and he was as glad to get back in the car as I.

The cheap breakfast was a buffet, of course, and a typical canteen sort of affair with its sticky baked beans, curling bacon, and leathery-looking tomatoes, eggs and mushrooms, that have all suffered from prolonged exposure to the tanning lamp that keeps them warm. It was delicious. After a bowl of muesli and fruit, I had to go back for a second plateful, and I lost count of the number of trips Wayne made. The news was on the overhead TVs. A german tourist had been killed the previous day when he failed to negotiate a cliff walk using the recommended route. Two hours ago I'd have known that he was a typically over-confident "expert" who assumed that rules were only for the other chumps. Now I'm not so sure. The only warnings the Giant's Staircase came with were that it was a long way to the bottom (which on reflection could have been a warning couched in a rather subtle example of Aussie humor) but nothing about the inherent dangers of the route and its equipment. There was more to come. Finally on the road, and still with time to kill (we wanted to be in Sydney in plenty of time for the Bridge Climb/rental return, but late enough that we could check our luggage into our room before abandoning the car) we turned off the highway at the first brown sign: Wentworth Falls. Here was another example of breathtaking trails.

|

We walk down the trail until we reach a cliff top lookout where a small group of like-minded tourists have gathered to admire the view of the falls on the other side of the valley. The falls again tumbled hundreds of feet from the Blue Mountains plateau into the valley below. Even at this distance we can see that the trail wades right through the water at the top of the falls with what appears to be a rope handrail to help prevent one from being swept over the edge, and then tumbles down the cliff itself in another series of ladders and goat trails until it finally crosses the stream again in the pools at the foot of the falls. |

|

We can see walkers wading across the top, and paddling in the pools at the bottom. Madness. We save this walk for another day.

Sydney beckons, but not before one last stop to photograph a flock of Sulphur-Crested Cockatoos idling around right on the roadside. We take about a hundred shots between us, but still can't get one with its crest unfurled, and the sun behind it (essential for the sulphur to shine in its true glory).

|

First order of business in downtown Sydney is to find the hotel. No problem, and there's even a break in the parked cars so I can pull out of the traffic for a minute or two while Wayne checks in and then brings out a porter. We pile up his wagon, then jump back into the traffic. We soon locate the Budget place, and drive on passed to get gas. There are three or four other folks pumping at the same time, one of whom is a person of female persuasion wearing one of those white billowy cotton dresses that the wind constantly seems to want to lift off her. It is hard not to stare, but it is worth it to check out how many other people are. It's like being in one of those movie segments where everything is frozen except the camera which moves through the scene. Here the traffic glides passed in slow-motion, with the only real movement being all the eyes tracking the dress. And the lack of underwear. No really. But I digress.

Back in the car, we swing into the Budget return lot, and before we've even parked the guy with the clipboard has put both our hackles up. One of us mutters "this is going to be trouble" but I don't remember who, not that it makes any difference because the other was already thinking it. Mr Clipboard is already strutting around the car as we get out. He says nothing, but makes two complete circuits, then starts testing doors, and checking the undercarriage. He has a problem, because there's not actually anything wrong with it.

| No scratches or dents, but the butterfly carcasses and the mud sprayed up from the wheel arches makes it clear we didn't just use it to ferry our luggage from the airport. Sure, if we were half our age, and had borrowed it for one night, then ask yourself where we've been. But we rented it six days and a thousand miles away—where the hell did he think it has been? Besides, the person who needs an attitude adjustment is Mr Clipboard, a peacock whose jaw is still flapping but which has still to utter anything coherent. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Blue Mountains

The Blue Mountains are part of the Great Dividing Range, which stretches

from Gippsland region of Victoria in the south to the tropical rainforests of north

Queensland. The range rivals the

Rockies in length, but nowhere

near in height. Australia's highest

mountain is Mount Kosciusko

about 500km S of Sydney. At

2,229m it is a mere baby by North

American and European standards.

Yet the Blue Mountains, peaking

at about 1,000m, proved a

heartbreaking challenge until they

were conquered by a trio of

explorers—Gregory Blaxland,

William Lawson and Charles

Wentworth in 1813. They and four

men hacked through dense bush

for 18 days to find a route. Sections of the Great Western Highway from Sydney

still follow parts of their trail.

The “Mountains”, as they are commonly called, stood between the still fledgling

settlement at Sydney and the agricultural and grazing country to the west. The

conquest of the Blue Mountains opened up the vast grain growing and sheep

grazing areas of New South Wales. East of the range the climate was too wet for

wheat and sheep, which developed foot rot.

The Blue Mountains are so named

because in the hot sun the vast forests

of eucalypts (commonly called

gum trees),

discharge a fine mist of eucalyptus

oil from their leaves. The mist

refracts light, which makes the

haze look blue at a distance. That

same oil makes the Australian

bush as volatile as a pine forest in

a bush (forest) fire. The vapor

explodes, causing the fire to race

through the canopy.

The settlement of the western slopes and plains established Australia's fine

wool and wheat industries, which created great wealth and are still very

important export industries. Australia led the world in the development of the

Merino sheep, imported from South Africa. It is still the finest sheep wool in the

world.

The first road was cut into the Blue Mountains by William Cox using a team of

30 convicts and eight guards. Starting at Emu Plains at the foothills in July 1814,

they cut an incredible 47 mi to Mount York (past the highest point of the

mountains at Mount Victoria – 1,064m) in just four months. At the end of six

months they completed 101mi of road to Bathurst, which was founded as the

major center for agriculture on the western slopes. The road was too steep for

horse-drawn carriages until another branch was built from Mount Victoria to the

historic township of Hartley in 1832. That could be considered the start of

tourism to the area. The first railway into the mountains, from Emu Plains to

Wentworth Falls, opened in July 1867. Trains now run to Katoomba and beyond.

The first motor car did not cross the Blue Mountains until 1904, and then it had

to be hitched to a horse to make the steep incline up Mount Victoria.

Katoomba

Katoomba is the largest town in

the Blue Mountains originally known for the Katoomba Coal

Mine opened in 1879. Named

after the Aboriginal tribe which inhabited the area, it is home to

the most famous site in the

mountains – the Three Sisters.

Legend has it they were three

beautiful young women who had

fallen in love with three men from

the Nepean tribe from the foothills. Tribal lore prohibited the union, and a battle

followed. A Katoomba witchdoctor turned the women to stone to prevent them

coming to harm, but he was killed in the battle and no one else could undo his

spell. They stand 906, 918 and 922m above sea level near the Echo Point

lookout at Cliff Drive, about 2km from the town center. Those

who are feeling very fit and energetic can walk down the 800 steps of the Giant

Stairway.

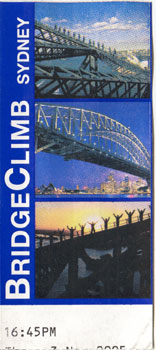

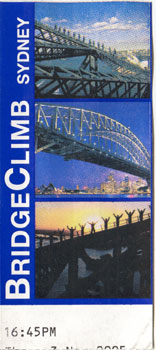

Sydney Harbor Bridge

Sydney Harbor Bridge (1923-1932) is the world's largest (but not longest) steel arch bridge. The Bridge's total length including

approach spans is 1,149m and its arch

span is 503m. The top of the arch is

134m above sea level and the clearance

for shipping under the deck is a spacious

49m. The total steelwork weighs 52,800

tonnes, including 39,000 tonnes in the

arch. The 49m wide deck makes Sydney

Harbor Bridge the widest Long span

Bridge in the world.

The Rocks

The Rocks is one of the most-visited parts of Sydney. Nestled at the foot of the Sydney Harbor Bridge and on the western shores of

Sydney Cove, The Rocks is the foundation place of Sydney and Australia. It is the oldest area of Sydney and has recently undergone an

amazing metamorphosis, the old district being transformed into a vibrant pocket

of cafes and restaurants and interesting tourist shops and stalls. This has been

achieved without destroying the area's Old World charm and historic buildings.

|

|

| |

|

|

Finally: "this way" and he leads Wayne into his shack, where his machine spits out a receipt which he tears off and hands over as if both the paper and Wayne are as dirty and damned as the car. "What's this $70?" "That car is absolutely filthy!" Mr Clipboard sneers."It'll need steam cleaning inside and out!" They exchange a few more words, but even from where I'm standing it is futile, so Wayne comes back out and says we'll check in at the rental counter. But Mr Clipboard saw that coming, and the receptionist is on the phone as we walk in. The look on the woman's face tells me she's still receiving input from him. I let the door hit me in the ass on the way out and stand on the sidewalk studying traffic while Wayne makes one last futile attempt to negotiate the bill.

|

Our chores complete, we walk back down to the quay side. We still have two or three hours to kill before the climb, so we agree to wander through the Rocks and check in at the Bridge Climb, to make sure we know where it is, and to ensure there are no snafus. We're also on the look out for "The Hero of Waterloo" a pub we admired on the Globetrotter TV show about Sydney. We stopped at an art gallery and priced the shipping on a six foot tall sea horse that was in their window. Cornie would have loved it, and although it was a bargain at $12,000, the $4,000 shipping charge put it beyond reach.

There's no sign of the pub by the time we get to the bridge. Checking in proves a good idea, because it turns out that our tickets buy us free access to one of the bridge piers, and we would not have time (or perhaps the inclination) to do that afterwards. It is extremely blustery on the sidewalk as we approach the pier, and once again I ponder the sanity of the whole event, especially as the view from the top of the pier is quite special enough, and cannot vary enormously from that of the top of the arch, which doesn't seem all that far from here, in elevation or in horizontal distance. I'd certainly recommend it as an alternative for those who have not committed the crazy amounts of money the climb itself is costing. The interior of the pier has some interesting memorabilia, and some great sculpture/statues depicting roles of the men constructing the bridge. |

Finally it is time to check in for the climb. They've clearly read from the Disney book on crowd control and entertainment. It takes a full 45 minutes from check in before you set off. We ponder how much is to do with hype/entertainment, and how much is truly safety/regulation. Their publicity gives you a pretty good idea of the carefully choreographed process:

You will be thoroughly briefed by the professional staff. Safety on the climb is their No. 1 priority and certain conditions will apply. A specially designed "BridgeSuit" worn over personal clothing, harness and communications equipment will be issued to each climber [we all have headsets so we can all comfortably hear the guide, and when needed, talk back to him] before commencing preparation on the climb simulator. All climbers are attached to a static line for the duration of the climb. A professional trained Climb Leader will accompany each group and will be able to answer any questions you may have in regards to the Harbor Bridge and Sydney sites. The Climb Leader will be equipped with the latest in digital photographic technology to capture the moment. All climbers are issued with a complimentary photograph of their climb group.

And let us not forget the breathalyzer. I have to say though, despite my personal tendencies towards skepticism, that the suit, to which absolutely everything must be attached, and the line to which we ourselves are ultimately attached, and which we all get to test for ourselves, definitely help to make me feel more comfortable. The climb leader also asks us about our fears, and strongly advises the chickens to be at the front of the group rather than the back. (Note that because you are "at all times" attached to the line, once you are hooked on, the order of the party cannot change.) There is a unanimous vote that I should follow the leader. Finally we're ready, and we set off up the street to the base of the pier we'd crested earlier that afternoon. After a couple of flights of stairs, we reach a landing which is the entrance to a tunnel that has clearly been cut in recent times right through the solid concrete of the pier, which is perhaps 30ft thick at this point. Ahead, outside, we can see the underbelly of the roadway. We clip on to the static line, first the climb leader, then me, then Wayne, then the rest of the group. There's a ball on the end of our harness lines that looks like a Rubric's Cube. Apparently invented by British teams in the America's cup, it enables the harness to run over the line anchors without needing to be detached. |

|

| The climb leader warns us that for most people, the first section, here under the roadway is the worst. Seems hard to believe, but he is right. We're 180ft up, and the catwalk is a mesh, so you can look straight down, first onto the quay side. traffic, then even worse, onto the water of the harbor. Sweaty palms again. But it is comforting to have the leader up front, and a crowd behind (who as the saying goes, will be coming through regardless). Then comes the major climb, up through a series of ship ladders until we appear on top of the arch. The fact that we have to duck under, climb over and squeeze through a number of obstacles on the way increases the sense that this is indeed a privileged experience, only enjoyed by professionals or the likes of us under professional guidance. I'm reminded of the ski trail across the glacier under Mont Blanc. The skiing isn't hard, but the opportunities for loss of life or limb are hidden, sudden, unexpected and frequent. Here too we're clearly in no immediate danger, (they take all comers, and in all weathers) but other than the line, and the occasional piece of foam protecting ones head from a particularly low or unexpected piece of girder, there are no concessions made to facilitate the route. |

|

Every 50 feet or so we stop and look back at the view. The leader, as promised, tries to balance keeping us entertained and informed with periods of quiet for us to simply absorb the view and the experience. Among the more interesting of the things we discussed:

- When the bridge was completed (in 1932) it had a 70 year life expectancy which you'll note has already expired.

- As part of the agreement to allow the enterprise, the Australian government made the Climb company responsible for bridge maintenance. Yes, in its entirety. 27% of ones dues goes into this fund. A recent survey of the bridge structure estimated its current life expectancy at 300 years.

- Climbs typically start every ten minutes or so, and run about 16 hours per day (depending on daylight), 363 days per year. December 30 and 31 are the two days when there are no tours, because that is when the pyrotechnic crews are packing the structure with New Year's Eve fireworks.

- Workers on the bridge had no safety lines or nets. But they only lost 7 men in the whole job. One man actually survived the fall. He threw his hammer into the water to break the surface tension, and entered feet first, which thrust his boots so far up his legs that they had to be cut off his thighs. He burst his ear drums, was unconscious for a week, retired from bridgework, and like everyone else, got no compensation with the exception of a gold watch the company presented to him for surviving.

- One worker lived within sight of the bridge. At lunchtime he would wave his lantern to show his wife where he was working, and his (pre-teen) daughter would bring his hot lunch to him. How times have changed.

- The Harbor View Hotel was a favorite watering hole for the men. It soon became clear that that the bridge was being build right over the site of the hotel. Realizing that if the hotel closed, they would lose their bar, at weekends they took the place apart, brick by brick, and rebuilt it 300 feet away. Which is why the Harbor View Hotel (still in business today) does not have a harbor view.

| At the very top, we have to switch to the west arch for the downward trip. The group in front of us have stopped half way across. At the back of their line are a guy and then last of all his girl friend. We can't hear anything, but he turns and gets down on one knee. There's a pause, then a lot of fumbling, then he gets up and they embrace. Their group is largely oblivious of course, because they are at the back, but our group cheers, and our climb leader takes a bunch of photographs. He's been doing these tours for 10 years, and has only seen this three times. The first guy to do it was so nervous he bounced the ring on the ironwork and a reputed $12,000 sailed over the side and into the harbor. Since they go to so much trouble to prevent anything from being loose enough to fall (liability being a fairly serious problem) it was clear that they'd have to have a solution to this problem, since it would only be a matter of time until it happened again. So now there is a special wrist cuff that one can request, which looks a pair of velcro handcuffs. The ring is threaded on the cuff, and the guy wears both cuffs until the moment of truth. If his proposal is accepted, he detaches one cuff and attaches it to his betrothed's wrist. He can then slide the ring down the cord "chain" and onto her finger. Once safe, he can give her his cuff too, thereby detaching himself. "Tough place to propose" our guide muses, "if she turns you down, you've still got her at your side for another hour." |

|

The final piece of useful information is that the leader is a local pub expert and he points some of them out to us on the way down. "What about 'The Hero of Waterloo'" I ask him. "How do you know about that?" "Globetrekkers!" "That's my absolute favorite" This is also his favorite time (we've deliberately chosen the last tour before the twilight/dark price hike), and as we'd hoped, the lights are starting to come on as we make our way down. Finally we're back and reverse through all the steps to return to our "civvies" and collect our souvenir pics.

|

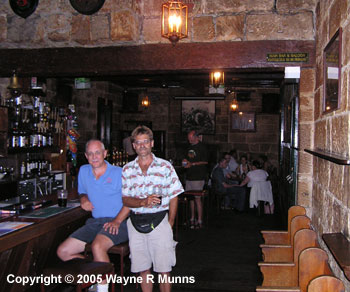

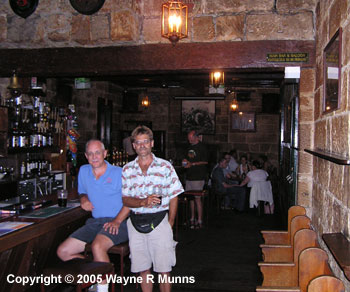

Back out on the street it is dark, and definitely beer time, so we make straight for the Hero, now we know roughly where it is. What a great little pub. Stone walls, timber roof, rough and dark, it has all the character and smell of a place that has been serving beer for several centuries, which is exactly what it has been doing. The first one goes down without touching the sides. We order another, which hits the spot. As we leave, a strange thing happens. I want a picture of the pub, but the only thing visible is the pub sign in its spot light. So I stop in the middle of the road hoping that I'm far enough back to get the whole pub, but close enough that the flash will fill in the doorway. I have absolutely no idea who these two women are, or whether they were posing for us, but if I ever saw them it was only for the one-hundreth of a second that the flash lit them up. I certainly have no conscious recollection of them being there. |

|

|

On the way back to the quay side. we pass the Harbor View Hotel in its convenient location away from the Harbor and right beside (but not under) the bridge. Towering over us is the pier with which we are now so familiar, and high above the pier swooping and swirling in the light are... what? By all that is reasonable, they should be bats. But they seem too big for "regular" bats and the fruit bats from the botanical gardens would surely not find much of interest up there. The flight pattern clearly indicates hunting, and we presume the target is moths attracted to the search lights. The most reliable source for an answer claims that these are sea gulls, but the darkness and the prey both make me skeptical. A mystery, but the eerie flutters of light provide a magical touch to the moment. |

|

We walk back along the quay side., and try to get some last pictures of the scene. Finally I could/should have used the tripod, but it is back in the room. Although the daylight has been too overcast to see the opera house in its glory, now at night we have a picture post card view of its characteristic shining white nuns/sails against the inky black sky. |

|

|

As we're on final approach to the hotel, we find a late night supermarket, and we explore it for some last minute souvenirs and supplies (Tim Tams, post cards, water) and to see if we can knock a couple more items off the treasure hunt. Barossa wine and Double Brie for example. Back in our room, Wayne composes a couple of splendid still-lifes out of them, and then we consume the evidence for supper. |

|

| There's a What's on in Sydney magazine to flip through, and I flip through it to see if there is anything serious that we missed in our myopic tour of Sydney. One particular ad catches my eye. Apparently there are ladies who can be rented out by the hour for entertainment purposes. Prices started at $2000/hr. We empty our pockets. We have about $13.75 between us. We do the math. We can afford about 25 seconds, which for young innocents such as ourselves, might be ample, and would surely be memorable. We chicken out and agree to save the money for emergencies tomorrow. It has been another long day, and tomorrow's 10,106 miles is going to take even longer. |

|